A Tale of Two Candidatas

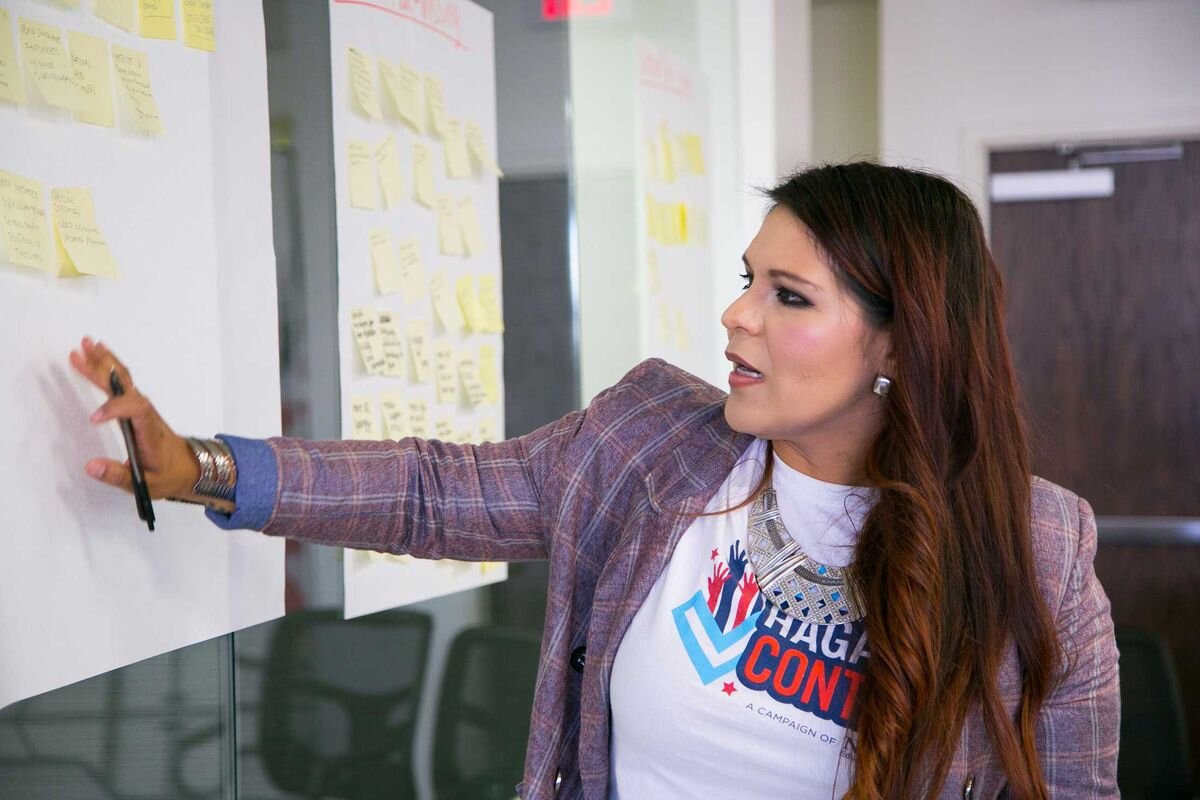

Maria del Rosario Palacios (left) and Beatriz Soto were once undocumented. Just after gaining U.S. citizenship, they jumped into campaigns to hold local political office.

Two young immigrants, formerly undocumented, are newly sworn U.S. citizens. They fearlessly jumped into politics, and then experienced very different outcomes

One young Latina wanted to be a candidate for state representative in Georgia.

Another is facing voters in rural western Colorado. She hopes to be the first Latina elected to local office in a county where immigrants make up a growing slice of the population.

They were once undocumented. They were able to become legal residents. And, recently, they took oaths as U.S. citizens.

Beatriz Soto has won the support of Democrats and other progressives in her run against an entrenched incumbent in the race for a commissioner’s seat in Garfield County, on the scenic western side of Colorado’s Rocky Mountains.

Georgia, a traditional conservative powerhouse, may yield a closer vote on Nov. 3, with a growing number of young voters and immigrants. Photo courtesy of Shutterstock

Maria del Rosario Palacios, on the other hand, describes her journey as a cautionary tale. She found herself caught up in a political firestorm, just a week before a primary vote in 2018. Today she’s an activist on behalf of voiceless, undocumented immigrants who dominate the payrolls at local poultry plants and farms.

Just after becoming U.S. citizens, the two community activists ignited campaigns for local office. Their decisions to run, they said, were not made lightly. The two were already brash activists, but they said they felt empowered to run by the confidence of new citizenship and the support of growing Latino populations in their communities.

Lizette Escobedo is director of civic engagement for the National Association of Latino Elected Officials. She was also once a candidate for local office in California. Photo courtesy of NALEO

“By 2028, Latinas will make up almost 10 percent of the labor force, and the number of Latinas with college degrees has doubled in the past 10 years to 4.8 million,” said Lizette Escobedo, director of civic engagement for the National Association of Latino Elected Officials. “As Latinas continue to play an increasingly larger and more important role in the U.S. economy and American institutions, they are increasingly seeing serving in public office as an important way to address issues that affect their neighborhoods and communities … Latinas are creating networks to specifically help Latina candidates raise funds, obtain endorsements, and find mentors to help with their bids for office as they become more successful in, and adept at, navigating traditionally white and male networks.”

Maria del Rosario Palacios: The Latina Who Kicked A Conservative Hornets Nest

The nightmare she’s lived through is not how 30-year-old Maria del Rosario Palacios imagined the trajectory of her new political life.

Since becoming a citizen, Palacios -- a single mother of three, community activist, and the daughter of migrant farmworkers from Mexico -- has run twice, for City Council in her home town of Gainesville, and then to be the area’s representative in the Georgia State House.

She had hoped to represent a booming population of immigrant Latino workers who, without the right to vote, power the region’s economy with their work in meatpacking facilities and on farms. Gainesville describes itself as the world capital of the poultry business. It’s solid Trump Country, in a swath of Georgia with a deep history of Jim Crow laws and racism.

Gainesville, in north Georgia, calls itself the poultry capital of the world. The industry is powered by legions of Latino immigrant workers. Photo courtesy of Shutterstock

Palacios, who’s lived in Gainesville since she was a child, came close to winning her bid for City Council. She lost when at-large votes from other parts of town swamped her support from people in her district.

“Had it just been the district voting, I would have won, but because we have at-large voting in place, I did not. So at least I can say I know my district wanted me to represent them,” said Palacios, adding that the experience led her to briefly consider running for mayor.

All about the demographics

Instead, Palacios ran for state office, representing Georgia’s 29th District. She ran, she said, to be a voice for undocumented residents who can’t vote, who face tough working environments and live in the shadows of local civic life, and who’ve experienced family separations because of deportations.

“When I was looking at the demographics in the district, we were in the bottom 10 percent of income. And in our district … the majority of households were children, and over 50 percent are run by a single parent,” Palacios said.

“We’ve never had someone represent us that knows these things firsthand,” she added, recalling her own time as a teenager, working in quality control inside a poultry plant. (Her mother still works in a poultry plant.) “It’d be great to have someone … speaking about poverty and being a single parent. But we don’t even have that.”

That all should have made for a good campaign platform. But in Georgia, her former immigration status would be enough to rain a ton of conservative political and legal bricks down on her. A Judge upheld GOP complaints that all the years Palacios had lived in Gainesville before citizenship didn’t count toward the residency requirements for Georgia politicians. She’s still digging out from under the mess.

Beatriz Soto: From Undocumented Immigrant To Political Firebrand

In western Colorado, 39-year-old Beatriz Soto wants to be commissioner for Garfield County, District 2.

An avid environmental conservationist, architect, and community organizer, Soto has much in common with Palacios: She was also once undocumented. And, for a time, Soto was a single mother.

Beatriz Soto and her son, Joaquin.

But Soto’s run for office was different from the start. Soto’s run started when the established Democratic Party candidate, Katrina Byars, asked Soto to replace her on the 2020 ballot. Soto grew more determined to run when she saw the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on local Latinos.

If Soto wins, she will make history, not because she will have unseated six-term Commissioner John Martin, but because she’d be the first Latina to hold that local office.

A need for representation

“In the history of Garfield County there has never been a Latina on the Board of County Commissioners, despite the fact that Latinos have lived here since before Colorado was a state,” Byars wrote in a Facebook post announcing her move.

“I think what really shifted and made us all realize a lack of representation was hurting our community to such a degree is when COVID hits our community,” Soto said. “Latinos are 30 percent of the population in Garfield County, and 70 percent of the coronavirus cases. Our local governments, towns, cities and counties, they’re scrambling … to make sure that this virus doesn’t spread, that the Latino community is informed.”

“I’m tied into the community, I know how to approach the community,” she added. “So I end up filling all these gaps, from advising, translating, delivering food, to helping average people connect to resources because they don’t know how. The system is not made for our community to access all these resources.”

Soto launched her campaign four months before Election Day. Holding to pandemic protocols, She announced her run in a video filmed in her backyard.

“When I decided to run, I was afraid that they’re going to use my story against me,” Soto said. “My story is a story of power, it’s a story of determination, it’s a story of resiliency … . I’m not going to hide it, I’m just going to put it out there and if people cannot accept you, and don’t think you’re capable, even though they can see all the great things you’ve done and everything you are doing for your community, then that’s something that I’m not going to be able to overcome.”

The Colorado River cuts a majestic path through Garfield County, where Mexican immigrant Beatriz Soto is running for local office. Photo by Serj Malomuzh/Shutterstock

A story of determination

Though she’s been a Colorado resident for many years, Soto’s story began in Chihuahua, Mexico.

“My father literally passed the Rio Grande with me in his arms when I was two years old,” she said. “My family established itself for a little while in (Houston) Texas and it was really hard for them and then they heard a rumor there was a lot of work in Florida. In (West Palm Beach) Florida they were very successful. They had their own drywall company,” Soto said.

When Soto was 10 years old, her parents were fooled by a crooked immigration lawyer into believing they’d won amnesty. Turns out the lawyer never submitted the application.

“I think that broke their hearts that they had that happen to them. So they decided to go back to Mexico,” Soto said, unable to hide the sadness that grips her every time she recounts her history. “So when I was in fourth grade, I get thrown into public school in Mexico.”

It was a huge cultural shift. She had to learn proper Spanish, not only speaking, but also reading and writing, in order to survive the tragedy that marred her time in Mexico: Within a year of returning to Chihuahua, Soto’s father was killed in an auto accident.

“Being the eldest in my family, I would see the bills and I would see my mom struggle and I would help her out as much as I could,” Soto recalled.

Her mother recovered, Soto said, and one day began dating a man who was visiting from the United States, and then followed him to Colorado. Soto followed later, and fell in love with the wild countryside along the Colorado River.

But after a time back in the U.S., on a tourist visa, Soto realized her dream of going to college was out of reach.

“I wasn’t able to go to college in the U.S. because this was the late ’90s and there was no DACA,” Soto said. “For universities to give tuition to undocumented kids … you know, it wasn’t a thing when I was ready to go to college, so I went back to Mexico.”

After college, an internship with a U.S. design firm led to a full-time job and the chance to represent Colorado in a competition in Chicago for emerging green builders.

Soto endured test after test to win legal residency and then citizenship. So there’s no fodder in her story, she said, for political opponents to use in a smear campaign.

“The Trump administration gave me my citizenship, they pulled my fingerprints, they looked at my story every time I’ve been in and out of the country,” she said. “I have absolutely no criminal record … That’s the only way that you can be approved for citizenship.”

Now she’s waiting for the ultimate stamp of approval: enough votes to hold political office.

Soto believes her chances of winning are pretty good. But because of the pandemic, she hasn’t planned a big celebration. People are hurting, she said. It would seem tone deaf to launch a big celebration.

Barriers All Around In Georgia

Maria del Rosario Palacios was a week away from the primary election in Gainesville when her world was turned upside down.

On May 14, 2018, the Georgia secretary of state took note of a challenge to Palacios’ eligibility for elected office. The letter reiterated that candidates must be citizens of Georgia for two years. Palacios had only become a U.S. citizen in 2017.

The complaint didn’t make sense, Palacios said. She could prove that she’d grown up in Gainesville.

Her parents moved her family to Georgia from Los Angeles after losing everything in a 1994 earthquake. Palacios attended elementary, high school, college and grad school in the area, so she reached out to the ACLU of Georgia for help and was initially confident she’d beat the residency challenge. Besides, in her earlier campaign, the residency clause had not come up.

But a state investigation ensued, and then-Georgia Secretary of State (and now Governor) Brian Kemp ruled Palacios didn’t meet residency requirements. Palacios and the ACLU appealed, but in a Fulton County courtroom, Palacios said, the judge dismissed the case without giving her lawyer a chance to argue.

Maria del Rosario Palacios, with her three children. Photo courtesy of CNN

A life of hard knocks

The reality of the end to her political ambition is something Palacios often thinks about. Especially when she considers the turns in her young life.

Her parents were legally working in the United States after establishing their permanent residency through Ronald Reagan’s amnesty program in the 1980s. But right before she was born, she said, her father decided he didn’t want Palacios to be born in the U.S. He did the same before the birth of each of her siblings.

“Two weeks before I was born ... he drove (my mother) straight to Guerrero where both of them are from and left her there. He took her green card, and then went back for us when I was two months old.”

Palacios said her father ultimately gained U.S. citizenship, but became abusive. He also never filed paperwork to ensure her own legal status.

She said she survived a rocky childhood filled with domestic violence and homelessness. Then at 15, she discovered she was undocumented.

By the time she was 19, her mother’s petition for the legal residency Palacios was entitled to finally succeeded. It helped her recover from the trauma of having been separated from her brother a few years before.

“When my brother was deported … I had an identity crisis,” Palacios said. “I had grown up

hearing from neighbors and friends, ‘why do you care so much about school if you’re not going to do anything with that piece of paper? It’s just going to be a piece of paper that you have no access to because you don’t have a right to be in the U.S., you don’t have a right to work or a right to do other things with your life,’ ” she said.

The hard knocks, Palacios said, prepared her for the next political assault.

Lost in translation

Election Day in 2018 came without Palacios on the ballot.

She had returned to her work with a local rights advocacy group when a call came in asking for someone to help a Spanish-speaking voter at a polling station.

“A friend … called to say that her newly naturalized, citizen mother was being given the runaround” at the voting station, Palacios said. The woman was told by election officials that she needed to show extra proof that she was a U.S. citizen, that her profile had been flagged.

Palacios was asked to translate. She said she stepped in, knowing that as long as they show a naturalization certificate or passport, new voters should be allowed to cast a regular ballot in Georgia.

Once at the polling station, Palacios said she met two others who needed translation help. She accompanied them inside.

Maria del Rosario Palacios has sparred with Georgia state elections officials over her eligibility to run for office. Photo courtesy of Shutterstock

That led to confusion. Some poll workers said Palacios had disrupted voting. Palacios said she was asking questions on behalf of non-English speaking people who believed they were being denied ballots. State elections officials are reviewing what happened at the polling station. Palacios described the event as a misunderstanding, and said she’s cooperating with the state review.

Today, Palacios is trying to recover from three years of political turbulence, mentally and financially. She holds three jobs and cares for her three children. She’s also working on a master’s degree in public administration. Oh, yes, and her mother is recovering from a coronavirus infection, which has kept her from returning to work.

Yet Palacios said she won’t stay silent. She continues to advocate for immigrant rights.

Gainesville has a significant population of undocumented immigrants, Palacios said, admitting that despite the strain, the doubts and the heartache, she’s quietly mulling a run for mayor next year.

—

Ruthy Muñoz is a freelance journalist, a multilingual linguist, and a soon-to-be book author. She served in the U.S. Army, reaching the rank of specialist during the Desert Shield/Desert Storm era. Previously, Ruthy was a Chips Quinn Scholar, and National Association of Black Journalists Reuters Fellow. She speaks five languages and was a French translator for Haiti’s national football team.

Ricardo Sandoval-Palos, managing editor for palabra. contributed to this report.