Gaming The System: Poor and in ICE detention

Illustration courtesy of el Nuevo Herald

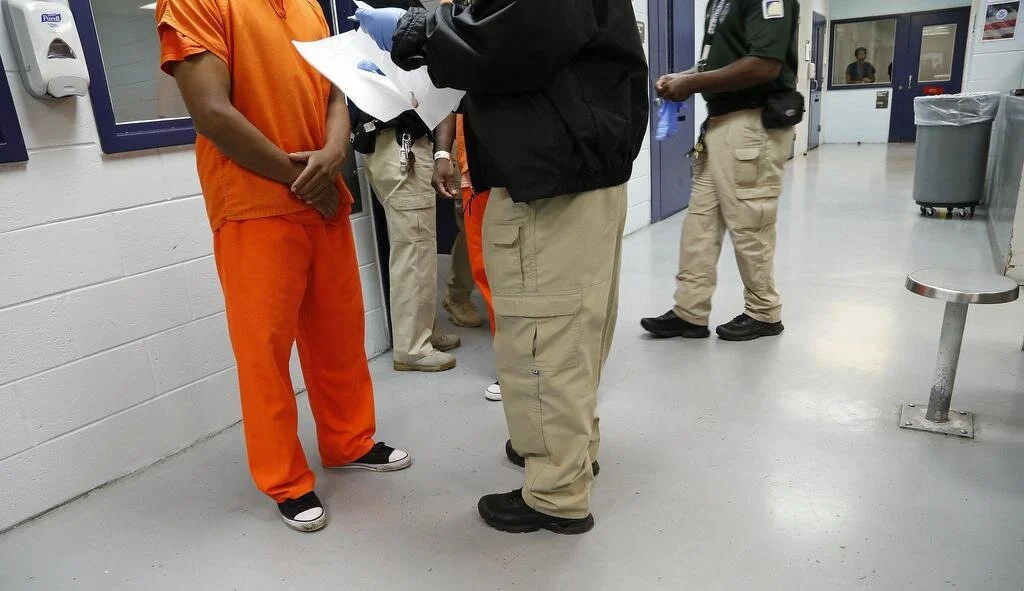

Some 50,000 people linger in the detention system run by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. They’re the low-hanging fruit of the immigration system, with no money and less legal support. Meanwhile, wealthy immigrants stave off deportation efforts from the comfort of their homes.

Editor’s Note: This report, the last of four published in palabra., is the result of a fellowship funded by the Fund for Investigative Journalism in partnership with the National Association of Hispanic Journalists and el Nuevo Herald of Miami.

The series first appeared in the Miami Herald.

The Spanish version, Jugando Con El Sistema, can be found it its entirety at el Nuevo Herald

Miryam López waited her turn in line.

The 55-year-old from Argentina came to the United States in 2002 on a tourist visa, fell in love, got married and in 2009 became a legal permanent resident. Except for a drug-related charge in 2012 that resulted in probation and a $763 fine, she lived a quiet life with her husband, Rudolph Marek, in Surfside — where Argentine empanadas are more plentiful than Cuban croquetas.

That peaceful life was disrupted in 2019 when she was picked up by immigration authorities, who came to her home and arrested López, shipping her to a detention center, where she has been fighting deportation ever since.

Some 50,000 people with limited legal resources now reside in a detention system run by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Photo courtesy of eNH/Walter Michot

Under the Trump administration, the country has become increasingly inhospitable for undocumented immigrants and those seeking asylum. But it has also recalibrated the treatment of legal permanent residents — referred to as “green card” holders — and naturalized citizens, affording zero tolerance for transgressions that would have been of little interest under previous administrations.

“It’s the byproduct of a couple of things: zero tolerance policies, and I mean this in the lack of discretion, and wasting a lot of resources that could be much better spent,” said John Sandweg, former acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and former acting general counsel for the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), in an interview with the Miami Herald.

This picture stands in sharp contrast to the universe of ultra-wealthy expats who have the money, the connections and the legal firepower to deflect prosecution efforts in their home countries while remaining off the radar of immigration officials in the United States. Many have made Miami their adoptive home.

Before the pandemic, roughly 50,000 foreign nationals were in ICE detention on any given day, often remaining for years, even as rich immigrants with serious legal issues were able to stave off incarceration and deportation. That pre-COVID figure was an increase of about 15,000 from the tail end of the Obama administration, when stays in detention averaged 27 days.

The number in detention has been decreasing since March as federal courts across the country ruled that ICE should release some detainees due to health concerns related to the coronavirus.

About 70% of the detainees during the Trump administration have had no prior criminal convictions, according to figures disclosed by ICE.

“By wasting your time and money on that person, someone dangerous is walking free,” added Sandweg, who served during the Obama administration.

Immigration detainees gather around a big screen during video-call time. Photo courtesy of eNH

Uneven priorities

In a memo to all ICE employees dated March 2, 2011, then-Director John Morton laid out what were and weren’t the agency’s priorities with regard to removals. The memo instructed agents to target immigrants “convicted of crimes, with a particular focus on violent criminals, felons, repeat offenders, members of gangs or individuals subject to outstanding criminal warrants.”

That changed under the incoming Trump administration, which came into office after a campaign built largely upon the bashing of asylum seekers and other immigrants and promises to build a “great, great wall” on the Mexican border.

Under Trump, DHS made everyone a priority, immigration advocates say.

Heriberto Hernandez, an attorney based in Lake Worth, says he has dozens of clients currently in detention and in immigration proceedings.

“Even if encountered by ICE, they would have been issued a notice to appear in court or simply released,” he said of the climate before January 2017. “They would likely not ever be detained nor transferred to an immigration detention facility.”

Nate Snyder, a former senior counterintelligence official at Homeland Security during the Obama administration, agreed.

The mission of law enforcement agencies has been “diluted,” Snyder told the Herald. “The capacity is not being focused on the real threats and those who are trying to take advantage of our system.”

López’s story is chronicled in Miami federal court as part of an ongoing class-action lawsuit against ICE. The suit, filed in April, seeks relief for thousands of immigrants detained — or once detained — in South Florida ICE facilities. The lawsuit cites the COVID-19 pandemic and the danger of the virus spreading when people are detained in close proximity to each other. Trial is scheduled for January 2021.

According to the documents, López was first flagged for “secondary inspection” by ICE at Miami International Airport in October 2016 after returning from her father’s funeral. Secondary inspections, basically an extra rigorous examination of documents primarily for foreign nationals, are a common practice by the Border Patrol when agents want to verify a passenger’s information.

López was told to return on Jan. 11, 2017, at which time she was informed that she would be placed in removal proceedings, but she was not taken into custody because of her chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a serious breathing disorder.

That was just over a week before the change of administrations.

As it turned out, the notice to appear was never filed with the courts, according to a copy of her dossier, provided to her counsel in response to a Freedom of Information Act request for records.

Play the Game

Have you ever wondered how the immigration system works for different people? Take your shot and play the game.

López is detained at Broward Transitional Center (BTC) in Pompano Beach, a facility privately run by GEO Group, a multi-billion-dollar company contracted by the federal government to run various detention centers and prisons across the country. BTC, one of three facilities at the center of the litigation, houses only low-level offenders and those with no criminal record.

On repeated occasions, ICE has refused to release López, stating that her eight-year-old crime constituted a case of moral turpitude, a legal catch-all term used to explain any behavior that deviates from community norms.

ICE has maintained that the law has always allowed the removal of any legal permanent resident who committed a crime within five years of admission to the country or has two convictions regardless of the length of time in the United States. Neither is a category that López fits.

“Lawful permanent residents are foreign nationals, and they are subject to being placed in removal proceedings under federal law,” said Nestor Yglesias, a spokesman for ICE.

While this isn’t a new standard, the way it’s being applied is.

López’s attorney, Linda Osberg-Brun, says her client’s breathing condition, known to ICE since 2017, should be factored into whether she is locked up during a pandemic.

“Detaining her now serves no useful government purpose and not only jeopardizes her life but also, the government’s interests by creating a likely possibility of another death while in its care,” she wrote in a letter to López’s deportation officer, Eric Green.

As of Oct. 9, there have been at least 10 reported coronavirus deaths of detainees in ICE custody, with more than 6,700 people having contracted the virus behind bars, data shows.

While undocumented immigrants await court dates or deportation inside ICE detention, wealthy immigrants in the legal system can consult with their lawyers from the comfort of their homes. Photo courtesy of eNH/Jose A. Iglesias

Tipping the scales

Adrian Sosa-Fleites, a Cuban national at the Krome detention center in Miami-Dade County, is another detainee who likely would not have been locked up under prior administrations. His attorney, Isadora Velázquez, says her 26-year-old client has no criminal record and has been behind bars for the 20 months since he arrived.

He entered the country in February 2019 through the U.S.-Mexico border, long after President Barack Obama ended the protections of the policy known as “wet foot, dry foot,” which allowed Cubans to apply for green cards a year and a day after arrival provided they made it to the United States.

Velázquez’s multiple petitions to the U.S. government for Sosa-Fleites’ release have continued to be ignored, she said. In her requests, she cites the ongoing class-action lawsuit in Miami federal court. The U.S. district judge overseeing the case, Marcia G. Cooke, has referred to ICE’s treatment of detainees at BTC, the Krome Processing Center in West Miami-Dade and the Glades County detention center in Moore Haven, Florida, during the COVID-19 pandemic as “cruel and unusual.”

Velázquez believes the filing of the lawsuit actually prompted the government to begin hopscotching detainees from facility to facility — to complicate the lives of those seeking relief in immigration court.

“That’s when it all became a hunting game,” Velázquez said. “When that lawsuit was filed, ICE began to transfer detainees across the U.S., making it harder for them to have access to family and legal counsel, thus making it extremely difficult for them to win their case.”

Since his apprehension in April 2019, Sosa-Fleites has been held at five different detention centers in multiple states, Velázquez said, noting that her boutique immigration firm, like many others, has represented financially burdened migrants like Sosa-Fleites without collecting a fee, while “having very little resources.”

A review of more than 1.2 million immigration cases from 2007-2012 found that immigrants in detention who had a lawyer were four times more likely to be released from detention than the broader population of immigrant detainees.

“The immigration system is so difficult to navigate even with great legal representation, but money can even that out quite a bit,” Sandweg said.

Unlike the U.S. criminal justice system, where those jailed or imprisoned have the right to legal counsel, in the immigration world that’s not the case, leaving thousands of immigrants without access to an attorney and more susceptible to deportation.

“You walk into immigration detention and you notice that everyone is mainly low income,” Velázquez said. “The system targets poor immigrants. We are not deporting the dangerous people. We are deporting the poor because they can’t afford to fight.”

She added: “We live in a place where people can basically buy their way out; that’s what the immigration system has become. To have a good case in immigration court, oftentimes you need to have an expert. You think the average person in detention can afford to go to a psychologist, who could then evaluate them and say that they were traumatized by something that happened [in their country]?”

She paused: “No, and if you don’t have those things, you’re not going to win asylum.”

Johnny Sarmiento was a legal permanent resident for 24 years before being detained as he prepared to go to his vending operations job. Sarmiento, 41, was apprehended at his home in August because of a domestic violence charge that occurred 14 years earlier with a former partner.

Sarmiento, who has since been released on bond but remains in deportation proceedings, said ICE “ambushed me at gunpoint when I was on my way to work.”

“I had walked out the door of my home and was in my car when three cars pulled up behind me,” Sarmiento said.

“At the end of it all, we had to make money we didn’t have, so that I could be released,” he added, noting that his wife reached out to gather about $7,000 in donations from family, friends and co-workers. “That’s money that takes more than half a year to make.”

In hopes of speeding up the deportation of immigrants caught up in the ICE dragnet, the Trump administration sought to hire new batches of immigration judges. The number of judges has nearly doubled. Those judges were then given quotas to clear 700 cases a year.

That, combined with efforts to make it more difficult for detainees to communicate with lawyers and gather evidence to support their efforts to remain in the United States, has put immigrants in a bind, immigration lawyers say.

Ashley Tabaddor, president of the National Association of Immigration Judges — the union that represents the arbiters across the United States — agrees that the quotas give ICE an edge.

“It’s creating systemic bias against granting [requests for release] because the government is creating an incentive to finish cases through procedural mechanisms,” said Tabaddor, an adjunct professor at UCLA’s school of law. “In other words: Quotas and deadlines create a systemic bias that leaves some people at a great disadvantage.”

Big bucks

The system created under the Trump administration has been a boon for one sector: the private prison industry.

Toward the end of the Obama administration, the president instructed the Department of Justice to stop signing contracts with private prison companies.

The Geo Group and another contractor, Core Civic, both with huge footprints in Florida, suffered reductions in stock prices of roughly 35%, the Miami Herald reported at the time.

President Trump rescinded the order shortly after taking office, sending both companies’ stock prices soaring.

According to ICE data, the cost of immigration detention is projected to be about $130 a day in fiscal year 2020-2021 — or around $47,450 a year per detainee. That math comes to about $25 million a year just for bed space at Krome (average of 542 beds), $22 million to run BTC (average of 476 beds) and around $18.2 million to run Glades (average of 384 beds).

Juan Carlos Gomez, director of Florida International University’s immigration law clinic, said “the system plays to the strengths of people with money. The pandemic just adds to the problem.”

“It’s simple: The poor are impacted disproportionately. And unfortunately, many of the people in detention — who are people of color — barely had the means to put food on the table for their families when they were outside of detention,” he said.

Sandweg, the former ICE chief, called people like López, Sarmiento and Sosa-Fleites “the low-hanging fruit of the immigration system.”

—

Romina Ruiz-Goiriena is a multimedia journalist and producer. She covers politics and immigration issues and has worked in Paris, Cuba, and Israel for France24, El Mundo, and Haaretz. In 2016 she co-founded Barrio, a digital news outlet that sought to make political news more accessible to Latinos. Previously, she worked in Guatemala and Central America for CNN and The Associated Press.

Monique O. Madan writes about immigration and enterprise for the Miami Herald. She is currently a Reveal Fellow at the Center for Investigative Reporting. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The Boston Herald and The Dallas Morning News.