Lecciones From Mexico City

Orion Collazo Schwietert and friends at school pickup in Mexico City. Photo by Francisco Collazo for palabra

One family’s quest for a better life and education for their U.S.-born children leads them south of the border

Words by Julie Schwietert Collazo, @collazoprojects. Images by Francisco Collazo.

The moment when I knew we’d made the right decision about our kids’ education came in an email inviting parents to sign their kids up for a visit to Mexico City’s National Anthropology Museum.

But this was no ordinary field trip. Students would ride in a double-decker bus from the school to the museum, accompanied along the way and at the museum by luchadores from Mexico’s Consejo Mundial de Lucha Libre (CMLL), who would talk with students about mujeres guerreras and the history of women warriors in Mexico’s diverse Indigenous cultures.

This, I thought, was the education I didn’t even know I wanted for my children.

My only complaint was that parents weren’t invited.

***

I was in Mexico City for a work trip on May 14, 2022, when 10 Black people were murdered at a Tops Supermarket in Buffalo, New York. (Three others, two white and one Black, were injured.) Ten days later, a shooter entered Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, killing 21 students and staff, and injuring several others. On the day of the Buffalo attack, my Black, immigrant husband was at home with our three children in New York City. When we spoke that night, I posed the question, “Why do we voluntarily remain in the United States? Why,” I asked him, “Don’t we return to Mexico City?”

To be able to ask that question entailed privilege for sure, privilege that isn’t available to many people who worry about violence. While our family is lower middle class in the United States, it would become upper middle class if we moved to Mexico, affording us even more protection. The question of moving also raised concerns among family and friends who worried about violence in Mexico.

I wasn’t naive about that violence, nor other problems in Mexico. Along with my husband, who came to the U.S. as a refugee from Cuba, I co-founded Immigrant Families Together, a nonprofit we created in 2018 as a response to the Trump administration’s family separation policy. In our work advocating for more than 130 asylum-seeking families supported by our organization (plus thousands more reached through our detention and border support programs), I’d heard numerous stories about the reasons why people flee Mexico – and the dangers asylum seekers from other countries face as they cross Mexico. I’d even written a book with one of those asylum seekers, The Book of Rosy/El libro de Rosy, which details those dangers. And as a fact checker who specializes in Latin American subjects for outlets such as palabra and The Atavist, I’m all too familiar with the statistics and, more importantly, the human stories of people impacted by widespread violence. “But,” I continued in my conversation with Francisco, “Kids don’t go to school alive and get shot up in their classrooms as a common occurrence.” And while anti-Blackness and racism exist in Mexico – and can have deadly consequences – it’s not routine for Black folks to go grocery shopping and end up bleeding out on aisle 9 because some racist decides to go on a shooting spree.

It didn’t take much to convince him. By early June, it was official: We obtained our residency visas and were ready to move.

Francisco and I had lived in Mexico’s capital from 2007-2009, pre-kids.

I hadn’t wanted to leave Mexico, but in 2009, two forces conspired to result in our return to the U.S. The first was that our residency visas weren’t renewed. At the time, Mexico didn’t have a rubric for substantiating freelance income, so we were told we had to abandon the country. The second was that the Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative went into effect, meaning that you couldn’t simply walk across the border with a U.S. driver’s license anymore. Francisco loved Mexico. But at the time, he loved New York more.

That love died during the Trump years. The xenophobia aided and abetted by stubborn racism in the U.S. became too personal. So when I raised the issue of returning to Mexico (which by then had a solid framework for assessing freelance income), Francisco was open to the idea.

I’d always wanted to come back to live, and I had often returned for work. And now, we were doing it. This time, with kids.

***

I arrived in Mexico City with our three children at the end of July, the beginning of the school year just a few weeks ahead of us. In New York, throughout the pandemic, I homeschooled our two youngest children. But as the worst of COVID began to recede, they expressed their desire to return to “real” school. They loved homeschool, they explained, but more than anything, they wanted to be with other kids for six hours a day. Mariel, 12, our eldest, wasn’t yet sure about what she wanted. (She eventually chose to attend an online school.)

In an effort to figure out where Orion, 8, and Olivia, 7, would go to school, I immersed myself in Facebook and WhatsApp parent groups, where parents from Mexico and around the world – Colombia, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, England, Latvia, and all points in between – shared experiences and offered advice.

Mexico City with kids, it seemed, would introduce a learning curve I hadn’t had in Mexico City without kids.

There were private schools with U.S. university-tuition price tags. There were public schools, but reports of pervasive bullying, especially of non-Mexican kids, discouraged me from this option. There were non-traditional schools – outdoor classroom schools, for example.

The choices were seemingly endless, and so were the opinions about each one. A former teacher warned against one private school’s narcissistic director and his cult following. Besides the bullying problem, public schools seemed to pose other problems, too. Francisco’s cousin, Ernesto, who had lived in Mexico for a decade after emigrating from Cuba, shared his experience as the parent of a former public school kid: “With all the asks for ‘colaboración’ for classroom and supplies, you’ll end up paying as much at public school as at private school.” His 7 year old went to a public school for a year before transferring to a private school focused on the Waldorf model, which emphasizes kids’ creativity and imagination.

Our private school costs – just over $1,000 a month for both kids – are impossible for families living in poverty, especially outside of the city. Even public school costs, where school supplies and shoe expenses are charged to families, are a serious strain on family resources. And of course having to forgo school to go to work is another reality for children living in poverty.

Data seem to affirm Ernesto’s experience: the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reports that within its member countries, Mexico has among the lowest per-student outlays. On average, OECD countries spend $10,722 USD per primary school student and $11,400 USD per secondary school student, while Mexico spends just under $3,000 USD per primary student and $2,890 USD for secondary students.

There were schools close to home that didn’t have space for both kids. There were schools far from home that would require two hours of travel – each way, twice per day. How was a parent supposed to make a choice, especially when they suddenly had privilege they’d never known in the U.S.?

Olivia Collazo Schwietert and Orion Collazo Schwietert outside their school, Colegio Montessori del Bosque. Photo by Francisco Collazo for palabra

Finally, with the start of the academic year just a few days away, I registered Orion and Olivia in a Montessori school, just over a mile away from our home. It was in a calm residential neighborhood, close enough to walk to and back. The school itself was located in what was once a large house, with a yard where kids enjoyed recess, had PE classes, participated in yoga on Fridays, grew kale and herbs, and picked oranges from a tree that shaded the patio. Students and their teachers walk to the neighborhood market on Thursdays to shop for fresh fruits and vegetables, and cook lunch together, and at home, my kids practiced for their turn saying, “buen provecho,” and a kind of secular grace before the meal: “Damos gracias a la naturaleza y a las personas que trabajaron para darnos estos alimentos.” (We give thanks to nature and the people who worked to give us this food.)

On our walks to school, the kids compared and contrasted what they liked about Mexico City versus NYC. Some of the differences were obvious and easy to articulate: Never, for example, had they built a big, beautiful Día de Muertos altar in their public school in New York, nor made a piñata and broken it gleefully with classmates as part of pre-Christmas celebrations. Though I discouraged such comparisons, inviting them instead to experience and love each place on its own terms, it was hard for me to follow my own advice. School in Mexico City was much more satisfying than in New York, and not just because of the focus on the community over the individual and on learning through play and fun.

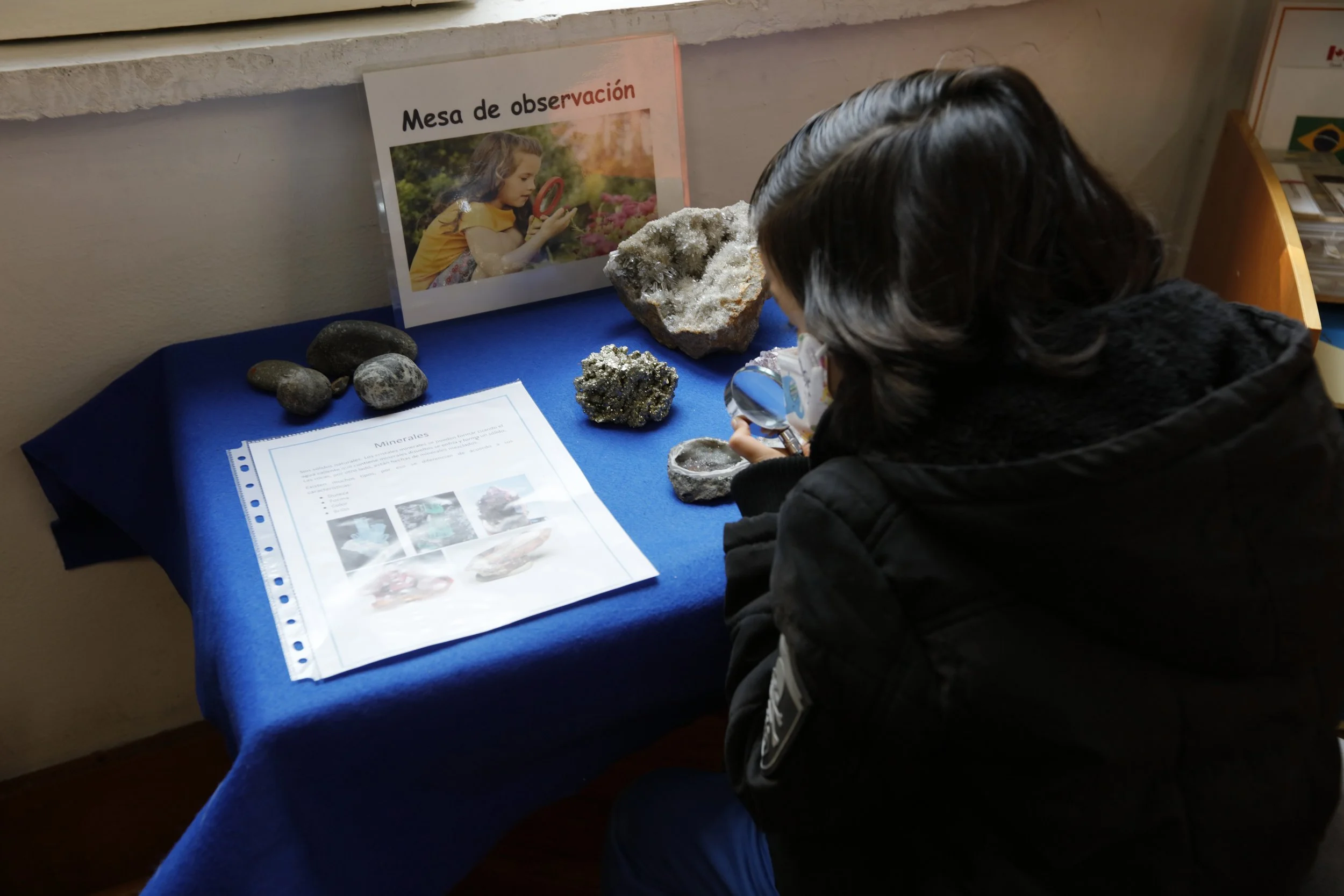

The Montessori method encourages curiosity among all students. Photo by Francisco Collazo for palabra

To be fair, figuring out education in New York had been a challenge, too. For one thing, people routinely offered “academic career” advice, even before I’d given birth to our first child. Everyone, it seemed, was an expert. They clucked sympathetically when I replied that I didn’t know what “our plan” was. “You really should have been thinking about this, like five years ago,” they’d say knowingly, pityingly, referencing waiting lists and lotteries and the kind of insider intel I thought was reserved for CEO suites or presidential war rooms, not elementary education.

There were intriguing private school options, like the United Nations International School, which we toured with our first child, Mariel. But by the time we had a second child – and well before we had our third– it was clear that the math could never add up: two creatives with freelance incomes + three kids did not equal more than $120,000 in annual tuition outlays. Public school it would be!

At first, I wasn’t worried. After all, I’d been a public school kid and I turned out just fine, and my husband was from Cuba, where education, including university, was universal and free – the idea that parents would pay for their children’s primary education was not only foreign; it was repugnant. “Everyone deserves the same quality education,” he grumbled repeatedly, and most forcefully after our first child took – at the age of four – a gifted and talented placement test. We were behind the ball there, too. While standing in line waiting to check-in, we learned that other families had dropped hundreds of dollars on “G&T” tutors to prep their children – yes, four and five year olds – for the test. As you can probably guess, we had not done this.

But still, I felt good about our choice. We lived in one of the most diverse counties and in one of the most progressive cities in the country. Public school couldn’t be that bad, could it?

Of course it could.

The #ENOUGH school walkout was a national, student-led gun violence protest, held on March 14, 2018. In a school with more than 1,000 students, Mariel, Schwietert’s eldest daughter, was the only child to walk out in protest. Photo by Julie Schwietert Collazo

And it didn’t take much time to see that. Though our kids’ school was ranked among the top 50% in the state, there was a lot that didn’t sit well with us. Class sizes were large. Teachers were frazzled and stretched thin. Teaching was oriented toward testing, which, in turn, was oriented toward the school maintaining its public-facing status as “a good school.” There was a roach problem (I knew, because I led a Girl Scout troop in the school’s cafeteria). Also, the curriculum seemed surprisingly conservative. After Mariel, brought home a Social Studies test where she’d been docked for defining a family as “a group of people who love each other” (the “correct” answer was: A mother, a father, and two children), I became that mother: the one who wrote passionate, progressive defenses on tests when I was just supposed to sign them. They weren’t just defenses for my kids. They were defenses for the world I wanted us all to live in.

All that would have been fine, Francisco and I told ourselves. We’d supplement our kids’ classroom learning with the values and lessons we wanted them to know. But it was the environment itself that was intolerable. School safety officers and crossing guards (both of whom are employed by the New York City Police Department) who yelled at kids as they got off their school buses in the morning. Active shooter drills where our middle child was told to hide in a closet because a bear – a bear! – was coming. A gun violence protest where Mariel was the only student to participate in the national school walkout. An administration that refused to reaffirm the school’s safety for Muslim families when the so-called Trump travel ban went into effect, telling me when I inquired about the school’s silence, that addressing the issue would be “too political,” and then after I offered to draft a letter that would not be “too political,” declining. They would not be addressing the issue, period.

If neither the academics nor the environment was redeeming, why, exactly, were our kids there for?

***

In the United States, we never had enough money to consider alternatives to a public school education. In Mexico, our relative economic stability (we’re still dealing with massive debt) opened possibilities to us that (a) would never have been available to us in New York, no matter how hard we worked, and (b) aren’t accessible for the “average” Mexican, who in 2022 earned 172.87 pesos a day, and in 2023 will earn 207.44 pesos a day – $8.60 USD and $11.26 USD, respectively.

This observation is even more true for Mexicans who live outside of economically productive urban areas and/or who are marginalized because of one or more aspects of their identity. I recognize that the choices available to my family are out of reach for too many people. But it is my hope that my children will choose to continue living in Mexico as they reach adulthood, and that they will join the grassroots groundswell that is fighting for educational equity for all Mexicans. Given that they have grown up alongside two activist parents who founded a nonprofit that supports Mexicans, Central Americans, South Americans, and folks from the Caribbean who are seeking asylum in the U.S., and they have been steeped in that work throughout their lives – including here in Mexico, where we have sheltered asylum-seeking families from Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela – I am confident they will.

This confidence comes in the form of a foundation of thought and action that is being poured by their own school. It was in the first parent-teacher conference that I took note of the most positive difference in my children’s education in Mexico: time, as well as a focus on true learning, not learning so the school could brag about achieving some state or national standard. During parent-teacher conferences in New York, which were scheduled for strictly enforced five-minute time slots, teachers always said, “Your kids are great; no problems; thanks for coming.” So I was taken aback when the Mexico City teacher team for our kids – yes, a team – met with us for nearly 20 minutes. They were obviously unhurried, went into detail about what was happening in the classroom, and then asked about what was happening in our kids’ lives – and ours – at home and in our community. They wanted us all to be partners in our children’s growth, not just at school. It seemed they wanted to be in conversation with us about how we all existed in our larger community.

Each Friday, students work together to prepare lunch for their classmates and teachers. Students visit the neighborhood fruit and vegetable market to purchase ingredients for each week’s lunch. Photo by Francisco Collazo for palabra

This feeling is reinforced across the entire school experience, from the school’s WhatsApp group for parents, where information and support are shared openly and easily and families organize mutual aid for social service projects they care about, to the leisurely family potluck dinner (complete with tequila and mezcal!) held in the schoolyard (it went on for hours, and no one was rushed to leave, even though it was a school night), to the holiday bazaar and kids’ Christmas performance, which sprawled beyond the show’s conclusion to include a long, lovely lunch and afternoon in the park. And the bonus: The only kind of drill the kids had to participate in was an earthquake drill, which was purposeful, organized, not frantic, and presented to kids in an honest, but age-appropriate way… no bears involved.

To be clear, I know this experience isn’t universal in Mexico City. Our experience is just one anecdote, in a relatively upscale neighborhood, in a family and community that have more resources and options than in many other places, especially rural, Indigenous, and marginalized communities. But those more important aspects of our children’s education here are reflected in other areas of society, too: the concern for community over the individual, the feeling that we’re all in this together, and the sense that we can always make time for one another – that we don’t have to hurry toward some arbitrary academic goal that ultimately means little, if anything, for the student and their learning.

During a recent trip back to the U.S. to visit my family, Olivia remarked wistfully toward the end of the trip that she was ready to return to Mexico. “It’s my happy place,” she said. “I want to live there forever.” With the foundation that is being set for her here, I have no doubt she will grow up to help shape a Mexican education system that offers to all students the same gifts she has been given here.

—

Julie Schwietert Collazo is a bilingual writer, editor, fact checker, and translator, as well as the co-founder and director of Immigrant Families Together, a nonprofit formed in 2018 to respond to the family separation policy. Along with Rosayra Pablo Cruz, she wrote The Book of Rosy/El libro de Rosy, published by HarperOne and HarperCollins Español in 2020. Both authors are featured in the documentary, “Split at the Root/Dividida en la Raíz,” which is streaming on Netflix.

Francisco Collazo is a photographer, chef, and co-founder of Immigrant Families Together.