Teaching Race in Arizona

A sign from protests in the 2000s against the banning of Mexican American Studies sits in Tucson High Magnet School teacher Brieanne Buttner’s Culturally Relevant Curriculum classroom. Photo by Rebecca Noble for palabra

Amidst a national climate of restriction — with states outlawing critical race theory in schools and conservatives banning books — Arizonans are in a rematch with a politician striking fear in educators who teach identity and racism

Haga clic aquí para leer el reportaje en español.

Words by Gabb Schivone, @GSchivone. Images by Rebecca Noble, @rnoblephoto. Edited by Lygia Navarro, @LygiaNavarro.

Imelda G. Cortez, a sophomore at Pueblo High School, didn’t want to be in the counselor’s office.

The older white counselor had asked to see Imelda’s mother, after trying, unsuccessfully, to dissuade Imelda from entering Tucson Unified School District’s Mexican American Studies (MAS) program. Why would she take Mexican American Studies, the counselor asked, if she was already in gifted classes and excelling academically?

Still, Imelda persisted. She knew what she wanted.

Exasperated, the counselor turned to Imelda’s mom, who looked at her daughter and smiled. In her best English, taking time to express each word, she assured the counselor that she trusted Imelda’s decisions.

MAS was a program, designed for Mexican American high schoolers but open to all students, that encouraged participants to think critically about history and strengthen their identities.

That's exactly what it did for Imelda. Before discovering MAS, Imelda felt that her reality wasn’t reflected in the books from which her teachers taught. As a MAS student, Imelda could speak Spanish — her first language — and learn about American history and literature from the perspective of fellow Mexican Americans.

MAS had existed in various forms since the late 1990s, around when Latino high school dropout rates of 27.8% were of significant concern. By the time Imelda entered the program in 2007, it was relatively small, although the district was 60% Latino. In the 53,000-student Tucson Unified School District, MAS comprised only around 800 students spread across eight schools — all Title 1 schools with a large percentage of low-income students.

Imelda G. Cortez, senior evaluation specialist for the University of Arizona’s Mexican American Studies program and a graduate student in the Teaching, Learning and Sociocultural Studies program, in her office in Tucson. Cortez was a student in the Mexican American Studies program at Pueblo High School as a junior. Photo by Rebecca Noble for palabra

For Imelda, MAS was eye-opening: Authors visited the classrooms. Desks were often arranged in a circle so students could look in each other’s eyes as equals. Teachers encouraged students to connect with their community through social justice research projects. Students learned new variants of ancestral Indigenous Maya and Nahuatl chants translated into English and Spanish, and discovered college-level concepts from radical leftist educators and philosophers like Paulo Freire and Antonio Gramsci, as well as the leading scholars of critical race theory.

In one remarkable case, Imelda recalls, MAS students at another school managed to change policy by creating a video that exposed a special education class in a low-income area being taught in a dirty garage used for shop class — a huge disparity compared to wealthier parts of town. The video embarrassed the district, which moved the class to a better facility.

Participating in MAS was life-changing for Imelda. But being in the program also meant stepping smack-dab into a pitched battle between the proponents of teaching marginalized perspectives and conservative state schools superintendent Tom Horne, who was in office from 2003 to 2011.

After Imelda graduated, Horne axed the MAS program — an act which a court would eventually declare illegal. But that didn’t stop Horne from being elected schools superintendent again in late 2022, nor did community criticism that Horne is dividing Arizonans rather than focusing on improvements for the state’s school children. Instead, the fight over what Arizona students should learn is raging once again.

From Community Engagement to Cancelation

Horne first became aware of MAS in 2006, after legendary labor leader Dolores Huerta spoke at a Tucson High School assembly. Huerta’s April visit became infamous when she was quoted in the local news saying, “Republicans hate Latinos.” A staunch Republican, Horne took offense.

Tito Romero was a junior at Tucson High at the time. Now 34 and cofounder of Flowers & Bullets, a Tucson community garden and radical advocacy group, Romero remembers the anti-immigrant hostility of spring 2006. Months earlier, in December 2005, the U.S. House of Representatives had passed the Republican-backed “Sensenbrenner Bill,” which would have made it a felony to be undocumented in the U.S. (The bill eventually failed to pass in the Senate.) In that bill, legislators approved the construction of enhanced security infrastructure along the U.S.-Mexico border without offering pathways to citizenship for the undocumented.

Students enter Tucson High Magnet School. Photo by Rebecca Noble for palabra

By March 2006, demonstrations were heating up nationwide in cities with large immigrant populations. When Huerta spoke to his MAS class at Tucson High, “It’s something that we all felt, experienced, were living through,” Romero says. On May 1 of that year, millions protested restrictions on undocumented immigrants nationwide, in what was dubbed “A Day Without Immigrants.”

After Huerta’s talk, Horne promptly dispatched his chief deputy, Margaret Garcia Dugan, to Tucson High to tell students that she was, in Horne’s words, “a proud Latina and a proud Republican, and she didn’t hate herself.”

Dugan’s appearance at a mandatory assembly irked students, especially because they were prohibited from asking her any questions. “We felt that Horne was just trying to tokenize a person, trying to scapegoat, trying to gaslight what we were feeling,” Romero says. “It was a communal agreement from the students that we’re understanding what was happening. We (were) going to use our freedom of speech to be able to protest this.”

A group of MAS students, including Romero, turned their backs on Dugan in silent protest. School staff escorted the students — fists raised — out of the auditorium.

Horne says he found this “very rude.” He learned that some of the students leading the protest were in an ethnic studies program called Mexican American Studies, or Raza Studies, after the political party La Raza Unida that emerged from the 1960s Chicano movement.

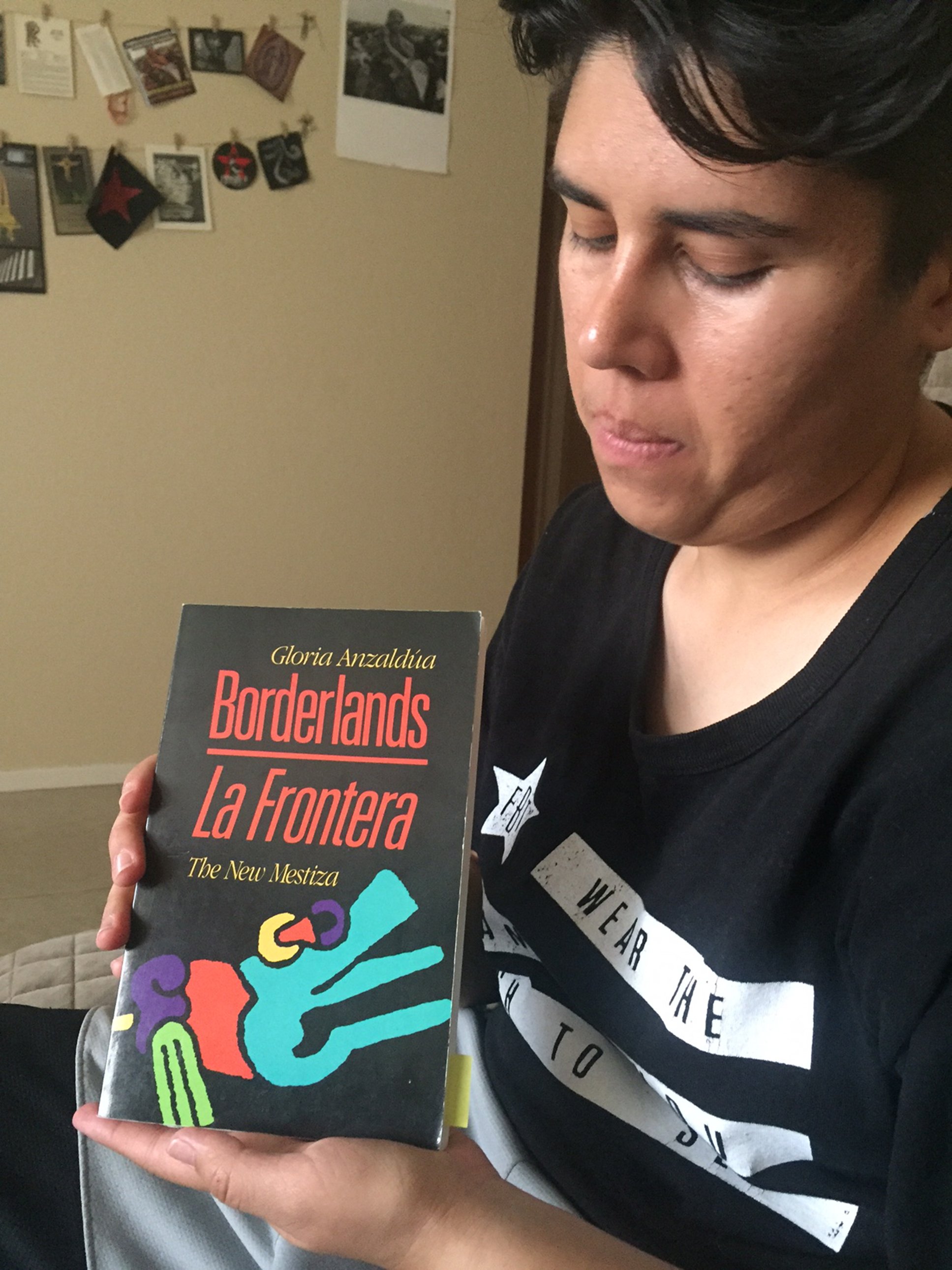

Imelda holds a copy of “Borderlands-La Frontera” by Gloria Anzaldúa, one of her favorite authors. The book was banned under HB 2281. Photo by Valeria Fernández

And so began Horne’s crusade. In June 2007 he wrote an "Open Letter to the Citizens of Tucson," in which he harangued students who protested Dugan’s speech, saying they "did not learn this rudeness at home, but from their Raza teachers."

To Horne, the literal translation of the word raza to “race” meant that MAS epitomized racial segregation. (Or, as he would later state during his 2022 reelection campaign: “Just like in the Old South.”) But for Latinos, la raza also can mean “the people” or “the community.” This phrase comes in part from the title of Mexican philosopher José Vasconcelos’ 1925 book, La raza cósmica, describing Latin America as an inherent blend of races and cultures which, he predicted, would diffuse, leading to an eventual disappearance of race.

Horne’s mission was to not only eliminate MAS from Tucson public schools, but to ensure that similar programs couldn’t be created elsewhere in Arizona. After lobbying for a spate of failed bills, HB 2281, which his cronies introduced to topple the MAS program, was signed into law in May 2010. (Horne claims to have written nearly all of HB 2281 himself, despite not being a legislator.) The bill prohibited public school courses “designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group,” from “advocat(ing) ethnic solidarity,” “promot(ing) resentment toward a race or class of people” or “promot(ing) the overthrow of the United States government.”

On Horne’s last weekday in office in his first term — Dec. 30, 2010 — he filed paperwork rebuking the Tucson Unified School District for violating the law. A year of external investigations (including one ordered by Horne’s successor) and student activism followed.

At first, the Tucson district defended MAS. But when Horne’s successor, John Huppenthal, initiated enforcement, withholding 10% of the state’s payment to the district per month until MAS was canceled, the board changed its stance. In response, MAS students organized a takeover of the school board. This sparked a national movement of supporters, including teachers and writers. Among them was the Librotraficante project, headed by self-proclaimed “book smuggler” Tony Diaz, an author and English professor in Houston who organized a caravan from Texas to transport carloads of books to Tucson.

Students at a MAS literature class taught by Norma Gonzalez at Rincon High School in 2011. Photo by Valeria Fernández

In January 2012, the district officially canceled MAS and ordered that all MAS books be removed from classrooms.

That morning at Pueblo High, Imelda’s teacher, Yolanda Sotelo, stared at a cardboard box she was supposed to fill with books. Immediately.

While Sotelo led class, an aide pulled all copies of the book students were studying, “Message to Aztlán: Selected Writings” by civil rights activist and poet Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales. Sotelo’s students were studying the epic poem “I am Joaquín.” The poem begins, “Yo soy Joaquín / perdido en un mundo de confusión / I am Joaquín, lost in a world of confusion / caught up in the whirl of a gringo society.”

In a small but defiant gesture, Sotelo remembers the head of the English department writing “Banned Books” on the box. A dark SUV waited outside the school and, according to Sotelo, an administrator drove the books to district headquarters, where they were hidden away.

“It makes me angry,” Sotelo says now. “They took away an important curriculum that the kids were enjoying, that we saw the kids reading — especially those kids who didn’t like reading Shakespeare or ‘The Great Gatsby’ or any of those pieces of the dead white guys.”

Books in Buttner’s classroom. Photo by Rebecca Noble for palabra

After MAS was canceled, a protracted federal court battle ensued. Students and teachers sued the state of Arizona, and finally, in 2013, Judge A. Wallace Tashima — a survivor of a Japanese internment camp in southwestern Arizona — sided with Horne, upholding the law’s constitutionality and accusing the plaintiffs of being too vague in their arguments.

But Tashima’s ruling also criticized Horne: “This single-minded focus on terminating the MAS program is at least suggestive of discriminatory intent,” he wrote.

By that point, Horne was the state attorney general, a position he was elected to in 2010 (after campaigning on his efforts to “stop La Raza”). He was defeated for reelection in 2014 and left political life for several years to practice private law. A month before losing the 2014 election, Arizona Secretary of State Ken Bennett released a memo stating reasonable cause that Horne violated state campaign finance laws.

Meanwhile, the MAS legal battle dragged on. In 2017, Tashima declared a permanent injunction on Horne’s law, citing “racial animus,” a legal term for malevolence or ill will toward others because of their race.

“The passage and enforcement of the law against the MAS program were motivated by anti-Mexican-American attitudes,” wrote Tashima in his ruling, referring to the roles that both Horne and his successor, Huppenthal, played in the banning of the initiative. Evidence presented during the trial included a series of pseudonymous comments by Huppenthal on political blogs, among them statements such as “MAS = KKK in a different color,” and “The rejection of American values and embracement of the values of Mexico in La Raza classrooms is the rejection of success and embracement of failure." In other blog comments, Huppenthal called MAS educators “infected teachers” and “MAS skinheads.”

Tashima also went on to say that “decisions regarding the MAS program were motivated by a desire to advance a political agenda by capitalizing on race-based fears.” Tashima said that was revealed by the “use of derogatory code words” referring to Mexican Americans that aligned with racist ideologies among some Arizona voters.

Buttner, left, speaks with fellow teacher Armando Bernal at Tucson High Magnet School. Photo by Rebecca Noble for palabra

“My philosophy is that we’re all individuals — brothers and sisters under the skin,” Horne told palabra recently in a sound bite rehearsed over many other media appearances. This philosophy is the center of Horne’s self-proclaimed “fifteen-year war against ethnic studies and critical race theory,” which he’s continued since his reelection as state superintendent in 2022. Horne stands passionately against treating “race as primary,” which he sees as the purpose of MAS. “That’s an evil value,” he says. “Poisonous.”

But for Tucson students, MAS was a lifeline. An education policy analysis found that, in the four full academic years prior to the ban, MAS students had an astonishing 90% graduation rate. Compared to students across Arizona in those four years, MAS students were 46 to 150% more likely to graduate. This is an especially striking fact given that, then as now, Latino dropout rates remain second only to those of Indigenous students.

Even this reporter — a Chicanx journalist who attended Tucson High but dropped out without knowing MAS existed — wonders what direction their education might have taken if they’d known about the beleaguered program.

The National Battle over Critical Race Theory

Since the MAS battle in Arizona, two national movements have surged: one to save ethnic studies and similar educational tactics, and another to quash them.

At its genesis, ethnic studies came from “systemically marginalized communities (that were) advocating for education services (and) self-determination,” says Dr. Nolan Cabrera, an education policy analyst at the University of Arizona who analyzed MAS graduation rates. After student rebellions in the late 1960s (including what is believed to be the largest university student strike in U.S. history), starting in 1969, ethnic studies departments opened in colleges across the country, utilizing interdisciplinary approaches to teach about current and historical social problems from the perspectives of race and ethnicity, gender and sexuality, and power and privilege.

Destani Grijalva is a student in Buttner’s Culturally Relevant Curriculum class at Tucson High Magnet School. Photo by Rebecca Noble for palabra

K-12 ethnic studies programs are still rare: According to research by Wayne Au, an education policy professor at the University of Washington, Bothell, as of 2020, nine states had laws or policies “that establish standards, create committees or authorize courses for K-12 ethnic studies specifically, or multicultural history more generally.” In another 12 states, such policies were proposed but failed to pass.

The remaining 29 states lack both ethnic studies mandates and legislative efforts to create them, making them potential battlegrounds for the fight over education on race. One of the main combatants is Florida governor Ron DeSantis, who has 2024 White House ambitions. In 2022, DeSantis signed a bill known as the “Stop WOKE Act,” which bans race-based discussion and analysis in schools and businesses. (The bill is currently under temporary injunction by a federal judge and not in effect.) This spring, DeSantis also successfully banned race-based conversations in the state’s public college and university classrooms.

Instead of “ethnic studies,” these days the tagword of conservative leaders like DeSantis is “critical race theory” (CRT). Watch TV news or pick up a newspaper, and you’ll undoubtedly witness fierce arguments about CRT, yet the very definition and nuances of the term are often lost in the debate.

‘Those topics make white people feel uncomfortable, particularly white conservatives, because it’s forcing them to reflect on themselves and their own privilege and their own power.’

The term emerged in the 1970s and 1980s as a scholarly concept highlighting the inherent racism and inequality built into American society, including law, culture and education.

Before 2020, major criticism of CRT actually came from liberal media and institutions that promoted “color blindness” as a solution to racial inequality. In the 1980s and 1990s, from the New York Times to the dean of Harvard Law School, complaints abounded of critical race theorists “on the faculty at almost every law school” pointing out “there are competing racial versions of reality that may never be reconciled” and who “reject the goal of integration.” Letters to The Times’ editor equated CRT with Adolf Hitler.

Currently, criticism of CRT comes almost solely from the other side of the aisle, and they are just as vicious — but now with added teeth intended to stop CRT from being taught.

Buttner in their classroom at Tucson High Magnet School. Photo by Rebecca Noble for palabra

Following the police murder of George Floyd in May 2020, anti-bias conversations and trainings proliferated in workplaces nationwide. In response, former President Trump issued an executive order prohibiting federally-funded entities from addressing inequality and racism by pointing to anyone “bear(ing) responsibility for actions committed in the past by other members of the same race” or causing “any individual (to) feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race.”

“That’s not what we’re trying to do,” says University of Arizona education professor Julio Cammarota, who focuses on participatory action research with Latino youth. “We’re trying to point out the structures and systems that support white supremacy and uphold white supremacy.”

He adds: “Those topics make white people feel uncomfortable, particularly white conservatives, because it’s forcing them to reflect on themselves and their own privilege and their own power, or how they’re perpetuating racism or white supremacy. … They don’t want to do that! They don’t want to abdicate or release that power and privilege.”

Since 2020, critical race theory — or how Republicans characterize it — has obsessed the Right. In a three-and-a-half-month period in the spring and summer of 2021, Fox News mentioned critical race theory 1,900 times.

The result has been waves of book bans and anti-CRT legislation since 2021. All but eight states have contended over bills or measures to limit critical race theory or discussions about race in public school classrooms. A total of 18 states have successfully passed bans regulating how teachers can provide instruction on racism, sexism, and other forms of inequality through legislatures or other avenues.

Buttner, center, shows their students how to plant seeds in the school garden at Tucson High Magnet School. The exercise is part of their Culturally Relevant Curriculum class. Photo by Rebecca Noble for palabra

One is South Carolina where, earlier this year, high school AP English teacher Mary Wood was reprimanded for teaching “Between the World and Me,” the National Book Award-winning memoir by Black author Ta-Nehisi Coates. Like in Sotelo’s Tucson High class in 2012, on school board orders, all copies of Coates’ book were collected mid-class, while some students frantically reread favorite sections.

The controversy began when two students reported Wood to the school board for the content of her teaching. “I actually felt ashamed to be Caucasian,” one of them wrote in their complaint.

“They don’t like the fact that we are naming the problem,” says Cammarota of people like the South Carolina students who complained. “They want to stop that whole process … just hoping that we ignore it completely.”

‘I’m the senior person in the country to fight critical race theory.’

According to the Washington Post, since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, at least 160 educators have lost their jobs for political reasons, including for supporting CRT.

Analyzing data encompassing 153 school districts in 2021, the Post recently found that the majority of book ban requests — mainly regarding LGBTQ+ or race-related content — came from just 11 individuals working to censor books en masse.

For Aja Martinez, a critical race theory expert at the University of North Texas, the latest nationwide backlash against the discipline is only one in a series of “flashpoints” in American history beginning with the desegregation of public schools following Brown v. Board of Education.

Nevertheless, the current controversies are unique in their scope and power, says Martinez, with “forces combining that we didn’t even really see happening with MAS in Tucson. Things get tested almost petri dish-like at the state level before they go national. We’re national now.”

An exercise from Buttner’s Culturally Relevant Curriculum class is displayed on a smart board at Tucson High Magnet School. Photo by Rebecca Noble for palabra

Back in Arizona, one of Tom Horne’s first acts upon returning to office in 2023 as state schools superintendent was to champion bill SB 1305, which would have prevented critical race theory from being taught in Arizona public schools. Democratic state Sen. Sally Ann Gonzales said on the Senate floor that the bill would “mute any open, honest, and factual discussion on American history.”

The bill died before being ratified. Yet Horne remains undeterred. He dreams of taking his fight national, claiming there’s a loophole in the MAS legal battle: a little-known expiration date on the permanent injunction against litigation on the program. After this date, Horne wants to take the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, which, he points out, “is even more conservative now.”

“I’m the senior person in the country to fight critical race theory,” Horne told palabra recently, with pragmatic self-assurance.

Cammarota, who helped develop the Mexican American Studies program in Tucson and has kept tabs on Horne for decades, says, “This is the way he was talking back in the early 2000s.”

“The right-wing is trying to ideologically obscure racism in this country as if it doesn’t exist. We have to struggle with empirical evidence,” Cammarota continues, “and have to articulate that in different segments of our society — whether it’s education, healthcare, the workplace, government, you name it —we need to have evidence to show there is a disparity everywhere. The reality is people are treated differently according to their race or ethnic identity.”

Horning in on Education on Race

For now, Horne has artfully figured out how to craft policy faster than through legislation and court cases.

This March, he inaugurated an Empowerment Hotline for complaints against teachers or schools perceived as subversive: “inappropriate lessons that detract from teaching academic standards such as those that focus on race or ethnicity, rather than individuals and merit, promoting gender ideology, social emotional learning, or inappropriate sexual content.” (No law exists in Arizona against teaching about any of those topics.) Horne’s hotline came after Virginia governor Glenn Youngkin launched an anti-CRT email tip line in his state in January 2022 that was deactivated months later due to scant calls.

Tom Horne with some of his trophies, awards and mementos in his Phoenix office. Photo by Gabb Schivone

According to the Arizona Department of Education, Empower Hotline has targeted at least two districts: the Catalina Foothills School District, for allowing students to choose their gender pronouns and keep them private from their parents; and Mesa Public Schools, reported for using the phrase “white supremacy” in a presentation on racial trauma.

“We could be focusing on education outcomes and supporting legislation that will make a positive impact on Arizona students but instead we have Tom Horne showing up to further tear and divide us,” says state Rep. Consuelo Hernandez, who represents District 21, a sliver of southeast Arizona on the U.S.-Mexico border.

Cammarota calls Horne’s brainchild “a snitch hotline” which “generates a lot of stress and anxiety among teachers who want to take a social justice perspective but now they have parents who will contact the state.”

“It really does feed into the larger narrative that we’re afraid of discussion,” says Mesa parent Christina Bustos, a former district teacher pursuing an educational policy PhD at Arizona State University. “We’re no longer having a conflict because we’re so polarized.”

Today, Imelda G. Cortez’s office in the Mexican American Studies department at the University of Arizona in Tucson is the size of her former high school counselor’s office. During a recent interview, Imelda pauses, becoming emotional recounting hearing that Horne was campaigning to be superintendent again. Horne’s MAS ban caused residual trauma that Imelda has blocked out. “I try not to think about it,” she says. “He’s definitely a huge trigger.”

After MAS, Imelda Cortez went to college and graduate school, eventually becoming a teacher at her old high school. She was working there when she heard of Horne’s bid for re-election. Friends and colleagues wanted to talk about it. People were upset, scared. When asked for her opinion, Imelda couldn’t even access the emotions necessary to discuss it.

Imelda G. Cortez was enrolled in the Mexican American Studies program at Pueblo High School as a junior in 2007. Photo by Rebecca Noble for palabra

MAS imprinted itself on Imelda. While her honors classes emphasized abstract-based critical thinking, MAS centered firsthand perspectives. She was hooked. “The literature we were engaging with was very different,” she says. “It was like stories that my mom could have told me. I was able to analyze things based on my experiences.”

Horne doesn’t believe that to be a valid educational strategy. “Our own experiences are very limited and the whole idea of education is that it expands our horizons,” he says.

Horne distinguishes between Mexican American Studies and what he calls a more “civilized” brand of education. “It’s really important that we advance civilization. In primitive civilizations, tribe is everything and any other tribe is the enemy,” Horne continues. “I feel like ethnic studies and critical race theory is a move backwards to a primitive development of civilization and that we need to go forwards and treat each other as individuals and (not) pay attention to race or ethnicity.”

The son of Polish Jewish refugees, Horne uses his own background as an argument: “If we could bring my parents back to life and say, ‘Do you think they should have had Polish studies?’ They’d think I was crazy.”

Feeding Young Minds

On a spring afternoon, Brieanne Buttner, a Chicanx teacher at Tucson High, prepares carne asada for their class to share. At a sizzling hotplate in the center of the classroom, Buttner talks with students about exams as slabs of beef hiss. Since the days of MAS, food has played an important role in the classroom here — reflecting Mexican American culture and nourishing low-income students from families experiencing food insecurity.

Today, Buttner, or “Mx B.” as students call them — using the genderqueer term, pronounced “Mix” — is teaching “U.S. History from a Mexican American Perspective” as part of the Tucson school district’s Culturally Relevant Curriculum (CRC).

Buttner heats tortillas before a potluck for their Culturally Relevant Curriculum class. Photo by Rebecca Noble for palabra

Since the late 1970s — after a consolidated lawsuit by the NAACP and the Mexican American Legal Defense and Education Fund charging that the district was engaging in racial segregation and discrimination of Black and Brown students — the Tucson Unified School District has been under a federal desegregation order. In response to the desegregation order, the district created the CRPI (Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and Instruction) Department, and CRC courses teach literature and social studies through Mexican American, Indigenous and African American lenses. After the long battle over MAS, the district strategically emphasizes that CRC classes are “academically rigorous,” “research-based,” and “diverse.”

Sam Brown was a lawyer for the Tucson school district from 2010 to 2016, at the height of the MAS controversy. He’s also a native Tucsonan.

“When we were going to Tucson High as Black kids in the ‘90s, we were angry about having to read Shakespeare instead of Maya Angelou,” Brown says. His classes, he continues, “did not reflect the history that our parents and grandparents were telling us about America. We felt like the history and the literature being taught was being taught by white people for white kids — and we just happened to be in the room.”

In fact, it was the Tucson school district itself — not the plaintiffs in the desegregation case — that argued for inclusion of the CRC classes in district curriculum. Brown considers that CRC is an improvement on the education he received, but not as radical as MAS. “I wish my Black teenage sons could have gotten that (kind of content) from a Black teacher with a Black perspective,” he says

Today, the number of students enrolled in CRC isn’t much greater than those in MAS when the program existed. Although the district itself says that CRC classes have resulted in “improved graduation rates, lower absenteeism, and matriculation to college” to date, four months after requesting records, it still hasn’t released CRC graduation rates for palabra to analyze compared to MAS graduation rates.

Leading their 11th graders through the cavernous marble halls of Arizona’s oldest high school, Buttner reminisces on their decade in ethnic studies as a student and educator. “It was my calling,” the four-year veteran teacher says, recounting how hearing about MAS as a college student made them move to Tucson to teach. The group continues through the vast courtyard to the student-run garden, where Buttner often takes students to volunteer and congregate under a cabana.

Destani Grijalva at Tucson High Magnet School. Photo by Rebecca Noble for palabra

Seventeen-year-old Destani Grijalva came to Buttner’s CRC class after José González, a former MAS teacher now teaching CRC at Tucson High, gave a presentation on CRC to prospective students. After learning “stereotypical history” during her freshman and sophomore years, in her junior year Destani was assigned to Buttner’s course, where she quickly grew to be a leader. When palabra met her, she had just been awarded “CRC Student of the Year,” an accomplishment Destani found especially rewarding given that she has a learning disability.

Destani plans to become a high school teacher, and would love to teach CRC. “It's my dream, honestly,” she says, sitting at a picnic table underneath the cabana, amidst the citrus, figs, and pomegranate trees growing in the garden. “(CRC has) really opened me up to who I actually am, and where my family's from, and how much we've actually gone through.”

After years of increased scrutiny due to its presumed links to MAS, only time will tell if the Tucson Unified School District’s CRC classes will survive until Destani becomes a teacher. Presently, state schools superintendent Tom Horne continues to show commitment to doing away with programs with which he disagrees. In September 2023, two months prior to publication of this article, Horne sued both the Arizona governor and attorney general in an attempt to get rid of the state’s over-20-year-old dual language program, in which students whose first language is not English receive half of their instruction in their native languages and half in English. In Horne’s view, English-only education is superior. Meanwhile, educators worry about what Horne might fix his sights on next.

While some in Arizona who’ve watched the MAS battle play out see the program as a precursor to the national battle over critical race theory, now the question is how much this countrywide conflict will ricochet back throughout Arizona. One thing is certain: Arizona students and teachers like Destani and Buttner won’t give up hard-won programs without a fight.

—

Gabb Schivone is a writer and investigative reporter originally from the borderlands of the Southwest U.S.

Rebecca Noble is a freelance photojournalist based in Tucson, Arizona and frequently contributes to the New York Times, Reuters, Bloomberg and other outlets.

Lygia Navarro is an award-winning disabled journalist working in narrative audio and print. She has reported from across Latin America, as well as on Latine stories in the United States and Europe. Lygia has reported for The American Prospect, Business Insider, Marketplace, The World, Latino USA, the Virginia Quarterly Review, the Christian Science Monitor, The Associated Press, and Afar, among other outlets. She has also worked as a podcast producer, and her work has been supported by many grants and fellowships, including, most recently, the Journalism & Women Symposium.