Air COVID-19

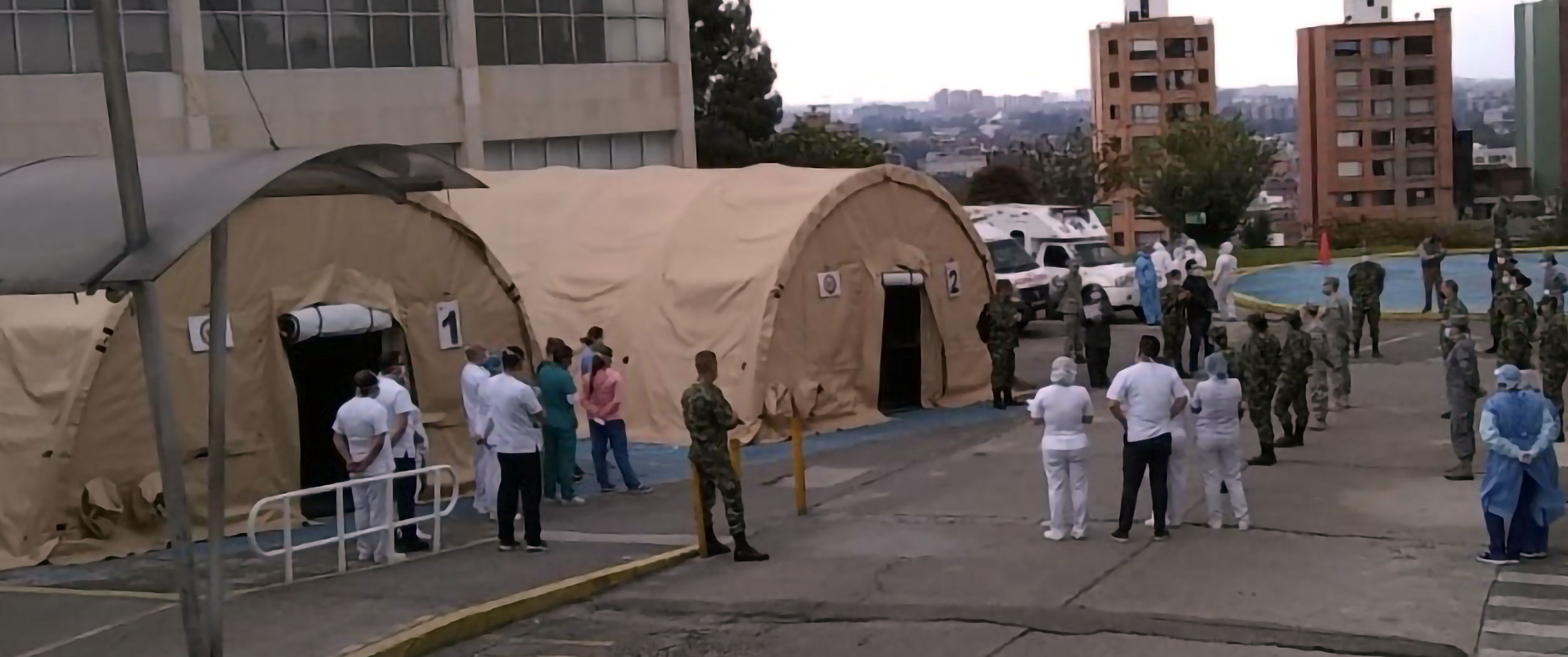

Medical and military personnel wait at a base near Bogota for the arrival of almost two dozen Colombian migrants who were deported by US immigration officials and came home infected with the coronavirus.

Deportation flights seed coronavirus in Latin America

Editor’s Note: This article is the first in a series that explores the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on communities in Latin America. It was reported and published with generous support from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

By Jenny Manrique

In early March, Carlos, a 24-year-old merchant, boarded a flight from Bogota, Colombia, headed to Indianapolis and a shopping and tourism spree with his aunt. There were toys and new clothes to buy for his newborn son, his first child.

But what Carlos said was designed as a short and fun getaway instead became a nightmare stay in the United States. It ended with him spending three weeks in a Florida detention center run by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, before being put on a chartered passenger jet on March 30 and sent back to Colombia.

A few hours later Carlos and dozens of fellow Colombian deportees landed in Bogota, where he learned he’d become infected with the COVID-19 virus that has paralyzed the world.

The jet was one in a fleet used in a sped-up deportation program run by ICE Air Operations (IAO). The number of flights increased just as the pandemic had started spreading like wildfire across the U.S. By mid-May, more than 300 flights had arrived in 19 Latin American countries with more than 70,000 deportees during 2020, according to ICE data.

The vast majority of those deportees were not tested for COVID-19 infection before being loaded onto planes and shipped home.

On the March 30 Bogota flight, several deportees interviewed by palabra. said the passengers were chained to their seats for most of the time in the air, and no one -- not even the crew -- wore masks or gloves. The ICE flights have drawn the ire of officials in Latin America now dealing with some of the world’s highest COVID-19 infection rates, ill-prepared health systems and, in some cases, unsupportive governments.

ICE has since shifted its policy and is now testing more and more deportees, but the moves were too late for deportees like Carlos, who complain the U.S. government negligently exposed them to a lethal virus.

“I traveled with a tourist visa, but during the stop in Miami the immigration officers interrogated me for several hours and then (claimed) that my intention was asking for political asylum, which was not,” said Carlos, speaking via telephone from Bogota, where he was being quarantined. “I don't speak English, I didn’t understand what was going on, but soon after I was detained, I was wearing a blue uniform, with no access to my cell phone or a jar of vitamins I travel with for health reasons,” he said.

(Carlos asked palabra. to use only his first name. He fears stigmatization and reprisal.)

Trapped in a hot spot

Carlos was held in the Krome Detention Center in Florida -- a facility that gained national attention this spring for becoming a COVID-19 hot spot, with at least 15 detainees and staff infected.

Carlos is convinced that the stay in Krome is likely when he picked up the virus that would make him something like a “Patient Zero” -- possibly a source of infection for at least 22 others who flew with him from Alexandria, La., on the repatriation flight.

“I signed up for voluntary deportation because I wasn’t fighting for any asylum case,” Carlos said, recalling the option presented to him by ICE officials as a fast way to get back home and avoid uncertain time in detention. “I just wanted to leave that prison where I was sharing space with more than 100 people … . Many of them showed cold and flu symptoms and nobody did nothing.”

On April 30th, U.S. District Court Judge Marcia Cooke ordered ICE to lower the number of detainees from 1,400 to about 350 in three detention centers in Florida, including Krome. By the time Carlos was detained, seven Krome detainees and eight staff members had tested positive for COVID-19, according to court filings.

“We constantly asked the guards why there were so many people entering the prison,'' Carlos said. “By the time we were hearing news about the coronavirus, (we were worried because) even priests were being allowed in to celebrate Mass.”

Nicolas Barrera, another Colombian on the March 30 Bogota-bound ICE flight, spent four months in ICE detention, between Krome and the Wakulla County Facility in Florida. In the Krome facility, he said, there was a building with close to 100 inmates in quarantine, “but suddenly all of us were mixed, and that is where the contagion and the panic began.”

“I saw many people coughing and suffering from colds,” Barrera said. “The bunk beds were extremely close to each other.”

Barrera, holding a tourist visa, arrived in Maryland in 2004 along with his mother. When the visa expired they sought asylum; his mother retired from the Colombian Army and was escaping death threats from that country’s largest revolutionary group, the Armed Revolutionary Forces of Colombia, known by its Spanish acronym, FARC. But they missed their first asylum hearing and decided to remain, undocumented, in the city of Gaithersburg, which was a sanctuary city.

In November of 2019, Barrera fell into ICE custody after police stopped him in Florida because his car had a cracked headlight. His lawyer suggested he apply again for asylum. But the courts were closed due to the virus and in the interim he was ordered deported. “I left my wife and three kids adrift (back in Maryland). I can't believe they deported me when I was trying to reopen my case. And now this nightmare.”

Like Carlos, Barrera was asymptomatic when he arrived in Bogota.

According to Diego Molano, director of the Presidential Administrative Department in Colombia, the government believed the deportees had been tested in the U.S. So, once the deportees were in Colombia, the Red Cross took their temperatures and then the Health Secretariat conducted additional screening.

An ICE statement at the time said agency protocols for immigrants who had “final orders of removal” included “a temperature screening at the flight line, prior to boarding” and an immediate referral to a medical provider for further evaluation if any detainee presents “a temperature of 99 degrees or higher.”

Nicolas Barrera

Testing in Colombia

“Once we entered the Colombian sky, passing over San Andres (island), ICE officers took off our handcuffs and gave us masks and gloves. I didn’t receive any of those during any of my transfers (to different ICE detention centers),” said Carlos.

After landing In Colombia, the 64 passengers (56 men and eight women) on the flight from Louisiana were put into quarantine at a military base south of Bogota. They were all tested and Carlos was the one deportee to come up positive for the coronavirus.

Colombia’s Ministry of Justice initial plan was to transport all deportees on the flight to a rehabilitation center in Tenjo, a small town near Bogota. But local residents blocked the entrance to their village with stones and dump trucks. They feared being infected by the deportees.

“As I suffer from allergic rhinitis, I had a rough first night sleeping in a tent (in the military base) with air conditioning,” Carlos recalled. “By the time the results came, I didn’t have any other symptoms, but I was immediately isolated.”

A second round of tests 10 days later revealed that 22 more deportees had the coronavirus. Carlos’ account was corroborated by six of the infected migrants who spoke to palabra.

“After the first positive (test), we started to take turns eating in smaller groups,” said Karen Rivera, 32, who is a nurse by training and helped the one doctor at the military base with taking temperatures and blood samples and doing other screening of the rest of the deportees, in 100 degree weather. She was also one of three women who tested positive after landing in Colombia.

“(In the base) we spent tons of time together without washing hands properly or just using disposable masks once and again,” Rivera said, speaking via telephone from the Hotel Tequendama in Bogota, where she spent 20 days quarantined with five other deportees after their positive test results. She became seriously ill: She suffered strong headaches “like a hangover,” muscle fatigue, diarrhea, loss of taste and smell, heartburn, and even panic attacks. She said she has an underlying condition, pulmonary edema, so she was “praying every day for my life.”

Julian Mesa

No social distancing in custody

Rivera is back in Colombia after a long stay in the U.S. that began with a flight from Mexico, where she had been living. In early February she was traveling to Tampa to visit her 9-year-old daughter. But on her first stop, Miami International Airport, her luggage was segregated by U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents for a random drug test. No drugs were found, but Rivera, who had a tourist visa, was accused of trying to enter the U.S. in order to work, which her visa didn’t allow.

Rivera was sent to the Broward Transitional Center (BTC) in Pompano, Fla. Like Krome, the Broward facility was ordered by a judge to decrease the inmate population because of the coronavirus outbreak.

“I was detained in a unit facility with 120 other women,” Rivera said. “We slept six per room, shared one bathroom and didn’t have access to toilet paper or feminine products … . We used to have recreation activities three times a day, but by mid-March there was a rumor of six infections and we were locked down 24 hours a day. … I didn't have access to my anxiety medication. On top of that, the arrests never stopped; (more people arrived) and the place was overcrowded.”

Although they said conditions in quarantine at the Colombian military base were better than in ICE detention centers, deportees described having to share spaces like bathrooms and small dining tables. They slept in bunks, 14 people per tent, with the exception of the eight women, who had their own tent. In all, 64 people had access to 12 toilets and 20 shower stalls.

“The hygiene was very irregular. We had a mop, a broom and a dustbin per tent. It was our duty to clean bathrooms but there was not enough soap, much less cleaning gloves,” said Julian Mesa, 34, who spoke from his house in Donmatias, Antioquia, a small Andean town located 30 miles outside Medellín. Migration from this small town to Boston’s east side -- where Mesa was detained in September 2019 by ICE -- has been so robust that today there are 4,000 Colombians living in this corner of New England.

“Once the number of the infected (from the March 30 flight) started to increase, ambulances arrived to transport us to our respective towns, to the Tequendama Hotel or the Military Hospital in Bogota. But there was so much improvisation,” Mesa recalled. “I had to ask my municipality for protection, so I won’t have any retaliation back at home.”

Throughout Latin America, deportees who have returned home from the United States, with or without coronavirus infections, have been threatened by locals. In Guatemala, villagers told federal government officials they would lynch one former detainee if he were allowed to come home.

For Mesa, the virus first revealed itself as a mild flu and pain in his joints. The whole journey was “frightening.” Mesa spent six months in the Bristol County House of Corrections in Massachusetts while waiting for a bond appeal so he could be set free while he waited for an asylum hearing. He said he was first taken into custody in 2013, in McAllen, Texas, after escaping threats in Colombia, crossing the U.S. border illegally and claiming asylum.

“I wanted to fight (for) my asylum but by mid-March when the Colombian Embassy confirmed (it would accept) the flight back to my country, I took the chance,” Mesa said. “The conditions inside Bristol were scary. Several guards were infected, two prisoners who tested positive were isolated, but we still were sharing bunk beds with more than 60 people per housing unit. We protested. Demanded tests. But that never happened.”

On May 12, U.S. District Court Judge William Young ordered the release of dozens of ICE detainees from Bristol County correctional facilities, after a class action filed on behalf of 148 people being held on civil immigration charges.

“This facility was notorious for bad medical care, bad sanitation and very high suicide rates, so we became very concerned about what was going to happen here after the coronavirus outbreak,” said Oren Nimni, staff attorney with Lawyers for Civil Rights, a rights group representing individuals in the lawsuit.

The judge ordered tests of all detainees and staff, and a release or transfer of immigrants in Bristol. To date, 18 ICE guards and nurses have tested positive and 50 detainees have been released. “We have reports from our clients inside that testing indeed has been increased,” Nimni said, adding that detainees still complain of threats from staff that anyone asking for a test will be put in solitary confinement.

Aristobulo Varon

Deportation: The way out

The situation in Bristol is similar to other ICE detention centers around the country where the Colombians on the March Bogota flight had been detained. Individual accounts decry a lack of social distancing, of testing and of face masks while in ICE custody and as they were moved to the pre-flight staging area in Louisiana.

Public health experts in the U.S. now say that, in optimistic scenarios, about seven of every 10 individuals in U.S. government immigration custody may become infected.

“I was detained with close to 100 people, the majority from Guatemala,” said Aristobulo Varon, 52, who was held for two months in the Port Isabel detention facility in Los Fresnos, Texas.

“When we heard the news of the number of deaths and the closure of (the U.S.) borders, we started to feel very anxious,” Varon said. “We saw some (Asian) inmates who were checked and then isolated. But it was not the case for the rest of us.”

Varon said he lived in Mexico for 20 years, and was apprehended after crossing the Rio Grande into Texas, near McAllen.

In the Port Isabel facility, Varon said he noticed that the stress of being so close to the threat of the virus was hitting some people hard, especially those who had waited years for a chance to fight their immigration cases in U.S. courts. Instead, he said, they became anxious for a chance to be evacuated.

He remembers seeing medical personnel go from bunker to bunker, talking about washing hands and keeping safe distances -- things that were impossible to do because of the crowded conditions. “Some activities like telephone calls, visits, and even the change of currency were suspended. They stopped allowing people to come inside the jail. But the uncertainty was bigger and some people discussed a hunger strike.”

Seven Colombian inmates at Port Isabel, including Varon, were elated when they heard they were going home. What they didn’t know was that they were about to spend several days in transit -- being transferred from one center to another. ICE often moves those with deportation orders through multiple facilities, collecting more detainees and then distributing them to 13 airports across the U.S. West and South, where they’re put on planes headed for Latin America.

Jenny Guerra

Transfers without PPE

For detainees bound for Colombia, one of the points of departure is an ICE facility near Alexandria, La., where at least 14 ICE employees have tested positive for COVID-19, according to the agency.

Former detainees told palabra. that before arriving in Louisiana, their ICE planes stopped in Georgia, Texas, Indiana, New Jersey, New Hampshire and Tennessee, to pick up more deportees. At no time during their journeys, they said, did any U.S. official follow standard anti-virus protocols of wearing masks or gloves or keeping passengers at social distances.

Carlos recalled that by the time he was ready to board his flight, he was already feeling body aches and had an irritating tickle in his throat. He said ICE officers offered him salt-water gargles.

Deportees on the flight were seated together, even though several said there were many empty seats on the chartered aircraft, which could carry 135 people.

“The transfer between facilities mixing people from one state to another is concerning,” said Eunice Cho Sr., a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Prison Project. “Staff are not wearing PPE (personal protective equipment) and are potential vectors. Even the detainees who spent time isolated are. There is no way to prevent transmission in the planes.”

Cho co-authored an ACLU report published earlier this year. “Justice-Free Zones” investigated immigrant detention centers that had opened during the Donald Trump presidency. The report highlights conditions at detention facilities that, once the COVID-19 pandemic began, became big problems for ICE: understaffing and cost-cutting measures in medical units, lack of access to proper hygiene, unsanitary conditions in living units, and prolonged detentions without parole.

The report looked at five detention centers, including the Jackson Parish Correctional Center in Louisiana, where five detainees, interviewed by palabra., spent at least four nights before their flight home.

“This is where more people complained about the lack of soap for bathing, or cleaning supplies for their cells or bathrooms,” said the ACLU’s Cho.

Gonzalo Botero

Dodging the COVID-19 bullet

Gonzalo Botero, 76, said he was held in those conditions before boarding the March 30 flight to Bogota. The oldest on that flight, Botero suffers from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). After surviving the coronavirus, Botero said he now feels “very fortunate to be alive.”

“The most irresponsible thing (the Colombian government did) was to send me home after the positive result for COVID-19, because I then infected my wife and her nephew,” said Botero from his house in Dosquebradas, a small town in the foothills of the Andes in western Colombia. “(My wife) lost 28 pounds in 10 days.”

Yet everyone in the family survived the disease and recently celebrated Botero’s birthday.

The longtime delivery truck driver said his body is still wracked with bone pain and chills, and he often has a hard time breathing.

Before his deportation, Botero spent two weeks at the Winn Correctional Center in Louisiana. There, Botero recalled, he repeatedly asked for a voluntary deportation. He had completed a three-year prison sentence for drug trafficking and was eager to go home.

“I was freed (from prison) but spent two more months locked up, first in New Jersey and then in Louisiana, with no access to medication or doctors,” Botero said, a claim that mirrors ACLU research showing the Winn facility has had problems with inadequate medical staffing.

Understaffing was also a problem in detention centers in Texas, according to immigrants who spent time in those facilities. Jenny Guerra, 30, was detained February 26 in the Rio Grande Valley after crossing the border with the hope of working and saving money for treatment for her epilepsy, which is not covered by insurance in Colombia.

She was sent to a U.S. Customs and Border Protection holding Center in Donna, Texas, where she slept in a tent complex with 50 women. After being transferred to a nearby ICE facility, she found herself locked up with dozens of other women. She said they slept in bunk beds, shared a few shower stalls and toilets, and had no access to soap.

“If there were rumors of (coronavirus) contagion, the guards isolated the dorm, but no doctor came to check on us,” Guerra said on a phone call from her house in Medellin where she was recovering from COVID-19. “I had a throat infection, but it was not until I got to Colombia that I had access to amoxicillin and antibiotics.”

When she heard of Carlos’ infection -- she, too, was on the March 30 Bogota flight -- Guerra said she felt there was no way for her to be safe.

“I felt I took good care of myself but this virus is like a lottery. And I won it,” she said.

A doctor leaves a barracks near Bogota housing some of the Colombian deportees who returned this spring from the United States infected with the coronavirus.

A questionable coronavirus strategy

Although Colombia was the first Latin American country to run diagnostic tests in early February, its National Institute of Health has been under scrutiny for its capacity to deliver accurate and fast test results: Technical issues, broken machines and false negatives were part of Colombia’s coronavirus problem.

The institute said it wouldn't discuss confidential health records. That makes it difficult to determine if Carlos was actually the one who spread the virus on the plane. Half of the deportees on the flight have said they never received results of two different tests they took after arriving in Colombia.

As of June 30, there had been more than 95,000 reported cases and 3,200 deaths due to coronavirus in Colombia. The government extended mandatory preventive isolation until July 15, slowly opening shopping centers, hair salons and museums, while restaurants, bars and gyms remain closed.

Even though nearly half a million Colombians have been fined for violating the quarantine, according to the Ministry of Defense, Colombia has significantly fewer cases than other countries in Latin America. According to data from the Worldometer, the pandemic in Brazil has killed almost 57,000 people and the cases are rapidly rising to a million and a half contagions. Peru (282,000 cases) and Chile (279,000 cases) followed the thread in contagions but the number of deaths in those countries (9,500 and 5,600 respectively) are below the count in Mexico, where 27,000 deaths and more than 220,000 cases have been reported.

All these countries are receiving deportees from the U.S. Government. Guatemala for instance halted ICE flights after dozens of passengers were infected with COVID-19. “Our hospitals have limited capacity, but now we have to treat these patients infected with a disease that didn’t originate here,” Guatemalan President Alejandro Giammattei said during a recent interview with the Atlantic Council in Washington, D.C.

More than 300 flights

Despite all this, ICE deportation flights have continued to Central and Latin America, among other global destinations.

Witness by the Border, a nonprofit based in Brownsville, Texas, tracked 324 ICE deportation flights from Jan.1 to May 7. According to its analysis of data collected by Flight Aware, airports in Texas were the points of departure for more than half of the ICE flights. Another 17% flew from Louisiana, and 7% more from Florida. The rest departed from cities in California and Arizona. Destinations have included Barbados, Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico and Nicaragua.

Another survey, by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), found that between Feb. 3 and June 30, there were 366 likely ICE Air deportation flights to Latin America and Caribbean countries. CEPR adds daily updates to a database that shows departure and arrival cities, as well as dates and times.

ICE officials provided data to palabra. detailing the number of deportees per country, between Jan. 1 and May 2. The report includes deportations via ICE Air, commercial flights, and a smaller number of people driven over the U.S.-Mexico border.

With 26,000, Guatemala has received the highest numbers of deportees. It’s followed by the two other countries in Central America’s Northern Triangle: Honduras, with 17,500, and El Salvador, with almost 11,000. In South America, Ecuador, with 2,000 deportees, and Brazil, with another 1,500, are suffering some of the region’s worst outbreaks of COVID-19.

According to ICE, 604 citizens were deported to Colombia between January and May 2 of this year. More have arrived since ICE changed its pre-flight protocols for detainees: All detainees on May 4 were tested before boarding a Bogota-bound plane, according to some among the 52 people on the flight. Two more groups of Colombian deportees landed in Bogota, on May 25 and June 22. There are no reports yet of infections among passengers on those flights.

ICE said the new procedures responded to orders in late April to get some 2,000 tests each month from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) “to screen aliens in its care and custody.”

“Given nationwide shortages,” an ICE spokesperson said in an email, “the agency likely won’t have enough (test kits) to test all aliens scheduled for future removals; therefore, under such a scenario, ICE would test a sample of the population and provide the respective foreign government with results.”

In a recent press release, ICE also announced that it is offering “voluntary tests” for the virus to all people held at detention facilities in Tacoma, Wash., and Aurora, Colo., and will consider doing the same at other locations.

The changes won’t hold off legal challenges by deportees on the March 30 Bogota flight. They said they are planning to sue the Colombian and U.S. governments.

Carlos, meanwhile, says he’s young and that his body was able to fight the virus.

He is now back in his home town of Antioquia, outside of Medellin. He says he has recurring dreams of a coronavirus vaccine and of never having tried to visit his aunt in Indianapolis.

As soon as he recovered, Carlos was allowed to reunite with his family. He finally met his newborn son. He went out and bought toys and clothes for him, in Colombia.

Jenny Manrique is a freelance reporter who has covered human rights in Latin America and the United States for two decades. She covered immigration for the Dallas Morning News and national politics for Univision. Her work has been published, in English and Spanish, in The New York Times, The Boston Globe, and CNN, among others. Follow @jennymanriquec on Twitter.