A Bump in the Road

A lack of immigration reform means that for undocumented immigrants, traffic stops have become harrowing encounters with law enforcement, as driving without a driver’s license could lead to deportation. Photo Victoria Ditkovsky via Shutterstock

A Massachusetts referendum is a test for laws that grant licenses to undocumented drivers

A decade and a half later, the traffic stop is still seared into Miguel Montalva Barba’s memory.

He was living in Orange County, California, studying toward his master’s degree in sociology at California State University, Los Angeles. He had just driven his cherry-red Honda Civic Hatchback through a four-way intersection after, he says, making a full stop when a police car flashed its lights.

Trouble loomed. An undocumented immigrant from Mexico, Montalva Barba was driving without a license.

“I was terrified,” he remembers. “I knew what this meant.”

An officer pulled him over and asked where he was going. Montalva Barba replied that he was headed to the Amtrak station to catch a train to class. The officer requested identification. Montalva Barba provided his student ID and the insurance papers for the Civic he shared with his brother, who was in the vehicle.

Montalva Barba wanted to know why he had been stopped. The response: A similar-looking car had been reported speeding. But the officer offered to let him go if he could name the song playing on the radio at that moment. Montalva Barba remembers that it might have been a Rod Stewart tune, but he didn’t know the title. The officer let him go anyway.

“I remember what a horrible show of power,” Montalva Barba says, “and also so trivial — ‘name the song and I’ll let you go.’”

Montalva Barba now lives in Massachusetts, where he is a professor of sociology at Salem State University. He has obtained permanent residency, and has been driving legally since 2020, which has given him “a sense of ease, a comfort in knowing if you are stopped, they will not necessarily put you in deportation proceedings. (Driving without a license while undocumented) is a huge burden to carry.”

Miguel Montalva Barba. Photo courtesy Montalva Barba

Yet Montalva Barba is worried about the prospects for the Bay State’s undocumented immigrant drivers. This summer, Massachusetts joined a growing number of states that allow undocumented immigrants to apply for driver’s licenses. But opponents led a successful campaign to get the issue on the Nov. 8 ballot. That means that on Election Day, voters will have a chance to repeal the law before it ever takes effect.

When Massachusetts and Rhode Island approved driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants this year, it brought the total to 18 states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico that have adopted this provision. Supporters of the law argue that it eases commutes to work, trips to the doctor’s office and drop-offs at school. However, critics oppose giving a legal document to people who are in the country without papers, with some also raising the possibility of fraud.

The upcoming Massachusetts referendum represents a potential bump in the road for these types of laws. In the absence of Congressional action on immigration reform, it has been up to state legislatures and local governments to set the agenda. In some cities in Maryland, noncitizen immigrants can vote in local elections, while in the nation’s capital, the D.C. City Council has passed a bill for that same purpose.

More opportunities

It took several decades for Massachusetts to pass a law allowing undocumented immigrants to obtain driver’s licenses. This summer, the Democratic-majority state legislature approved a bill, called the Work and Family Mobility Act, overriding the veto of Republican Governor Charlie Baker. But the campaign to repeal the law reveals the vulnerability of state-led efforts to grant rights to undocumented immigrants.

“If the law is repealed, we won’t give up because immigrants without status will still be here and still need to drive,” Franklin Soults, a spokesman for Local 32BJ of the Service Employees International Union, wrote in an email. The union local helped lead the campaign to pass the Massachusetts law.

Soults adds: “The Republican Party has long refused to consider fixing the broken immigration system and creating a pathway to citizenship for those here without status. The vast majority of those without authorized status have no way to obtain it. This won’t change. Without a doubt, however, the fight to pass this sensible law would become much longer and harder in this state, and perhaps in other states as well, and anti-immigrant politicians would feel empowered to continue to use the issue as a wedge to leverage their careers.”

Elsewhere in the country, organizers are using the referendum process in efforts to expand opportunities for undocumented immigrants. On Election Day, Arizona voters will decide the fate of Proposition 308, which would make in-state college tuition available to undocumented students. If the measure passes, it will overturn a referendum approved by voters in 2006 that prohibited in-state tuition for non-citizen residents.

“The debate in Massachusetts on driver’s license eligibility for undocumented immigrants is generally consistent with that in other states,” Kevin R. Johnson, dean of the University of California at Davis School of Law, wrote in an email to palabra.

In 2004, Johnson authored an article titled “Driver’s Licenses for Undocumented Immigrants: The Future of Civil Rights Law?” that was published in the Nevada Law Journal. “(States) have a great deal of leeway on driver’s license eligibility, and the federal government’s unwillingness to create a uniform standard is understandable. Still, it has impacts, as these issues meander through various states, such as Massachusetts and Rhode Island,” Johnson explained to palabra.

Before this year, state legislation authorizing driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants had only infrequently been challenged by repeal efforts, according to Jackie Vimo, senior economic justice policy analyst at the National Immigration Law Center (NILC).

“Ultimately these efforts are rare,” Vimo wrote in an email. “The most notable repeal effort came from Oregon in 2019, and it was unsuccessful. Most state governments and their residents understand that it is in everyone’s best interest to make sure every driver is licensed, trained and insured, as this is what promotes the safety of everyone on the road. I think that’s why we’ve seen more momentum in the opposite direction, toward states moving to make driver’s licenses accessible for all people regardless of their immigration status.”

The NILC notes that almost 60% of foreign-born residents in the US (58.5%) live in the 18 states that have passed legislation allowing undocumented immigrants to obtain driver’s licenses.

Participants from the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition (MIRA) march in support of driver's licenses for the state’s undocumented immigrants. A "yes" vote on ballot Question 4 would approve a new state law enacting driver's licenses for undocumented immigrants, while a "no" vote would repeal the law. Photo courtesy MIRA

“At some point, I just had to drive,” Montalva Barba says of his motivation for getting behind the wheel without a license. “I just thought of my parents, brothers, family — folks who are still undocumented — and how much quality of life changes when you have access to driving, especially if you have to commute or you don’t live in a place where there’s adequate public transportation.”

Massachusetts resident Javier A. Juarez also understands these challenges. A Peruvian immigrant, Juarez is the senior director of advancement for the Massachusetts Immigrant and Refugee Advocacy Coalition (MIRA). He has been a Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipient since 2012, when then-President Barack Obama signed an executive order creating the program. Although DACA authorized Juarez to drive legally, he had already been driving without a license for three years in Rhode Island, where he lived at the time.

Karina Flores, a Salvadoran immigrant living in the heavily Hispanic neighborhood of East Boston, is also a DACA recipient with a driver’s license. She doesn’t get behind the wheel often these days, as she works remotely for Neighbors United for a Better East Boston (NUBE), a local nonprofit. However, when she was a student at Salem State, she drove to campus five days a week and to a job with nighttime hours, when the public transportation system did not run.

Flores worries that DACA could “end at any moment," which would mean she would be undocumented again. Therefore, she fears that if the Massachusetts law were repealed, it would hinder her ability to drive in the future.

Juarez believes that Massachusetts will vote to keep the Work and Family Mobility Act on the books. “I think we are confident the voters of Massachusetts will say ‘yes’ to safer roads,” he says, referencing Question 4 on the November ballot. A “yes” vote will support the legislation on driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants, while a “no” vote would repeal the legislation. “We are eagerly waiting for Massachusetts to become the (18th) state to implement reforms. States like California and Connecticut have seen decreases in hit-and-run accidents as a result.”

Overall, Juarez reflects, passage of the Massachusetts law “feels like a giant win, not only for the immigrant community, but for the state. It acknowledges that it’s simply just a transactional thing, providing people with safety, documentation for people to drive. It has been a long time coming, 15 to 20 years in the making.”

The most recent push in Massachusetts began in 2018. Two organizations — the Brazilian Worker Center (BWC), which supports immigrants on issues of workplace rights and immigration, and Local 32BJ of the SEIU, a union that represents property service workers in the U.S. — co-chaired a coalition dedicated to supporting driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants in the Bay State.

On Sept. 24, NUBE East Boston held events across East Boston to educate non-citizens about issues on the Nov. 8 election ballot, including driver's licenses for undocumented immigrants. Photo courtesy NUBE

Lenita Reason, executive director of the Brazilian Worker Center, predicts that the new law will benefit all industries.

“I think everyone that lives in Massachusetts needs to drive to get to work,” she said. “With the (Covid-19) pandemic, the needs grew even more. Many times, people would go together in a van. With the pandemic, we felt that if one person got Covid, if they drove many people, that could be an issue. I think in all industries, workers need to have the mobility to get to work. Families that have kids need to take their kids to school, go to doctor’s appointments, go grocery shopping. It will affect every resident in Massachusetts.”

Asked about broader connections to the national conversation on immigration, 32BJ spokesman Soults replied, “As others have said, even people who normally take conservative stances, driving and immigration are not necessarily connected.”

He added, “I think most Americans, most citizens, they consider how the majority of undocumented immigrants have been in this country over 10 years, with over two-thirds of that percentage more than ten years … they contribute millions, tens of millions in taxes in every state, often money they don’t get back themselves … I think when they share their individual stories, there’s real compassion.”

The law is scheduled to take effect on July 1, 2023. Qualifying applicants must show proof of both their identity and Massachusetts residency. The license granted is a standard Massachusetts license issued to any state resident who passes a road test.

Currently, undocumented immigrants cannot get a Massachusetts driver’s license, and are subject to a range of possible penalties if caught driving unlicensed.

“Usually, they get a ticket, their car is towed and they have to go to court in front of a judge,” Reason said, adding that in Massachusetts, standard court practice is to separate the traffic stop from immigration-related issues.

“Immigrants need to drive,” she says. “There may be anxiety or fear … Maybe they have a blinker broken. The police can pull you over if something’s not working. It can be stressful all the time.”

Montalva Barba recalled the fear he experienced when the police officer stopped him in California.

“We knew that traffic stops, essentially any contact with the police, could lead to deportation proceedings on American soil,” he said. “You drive with almost overly-cautious driving.”

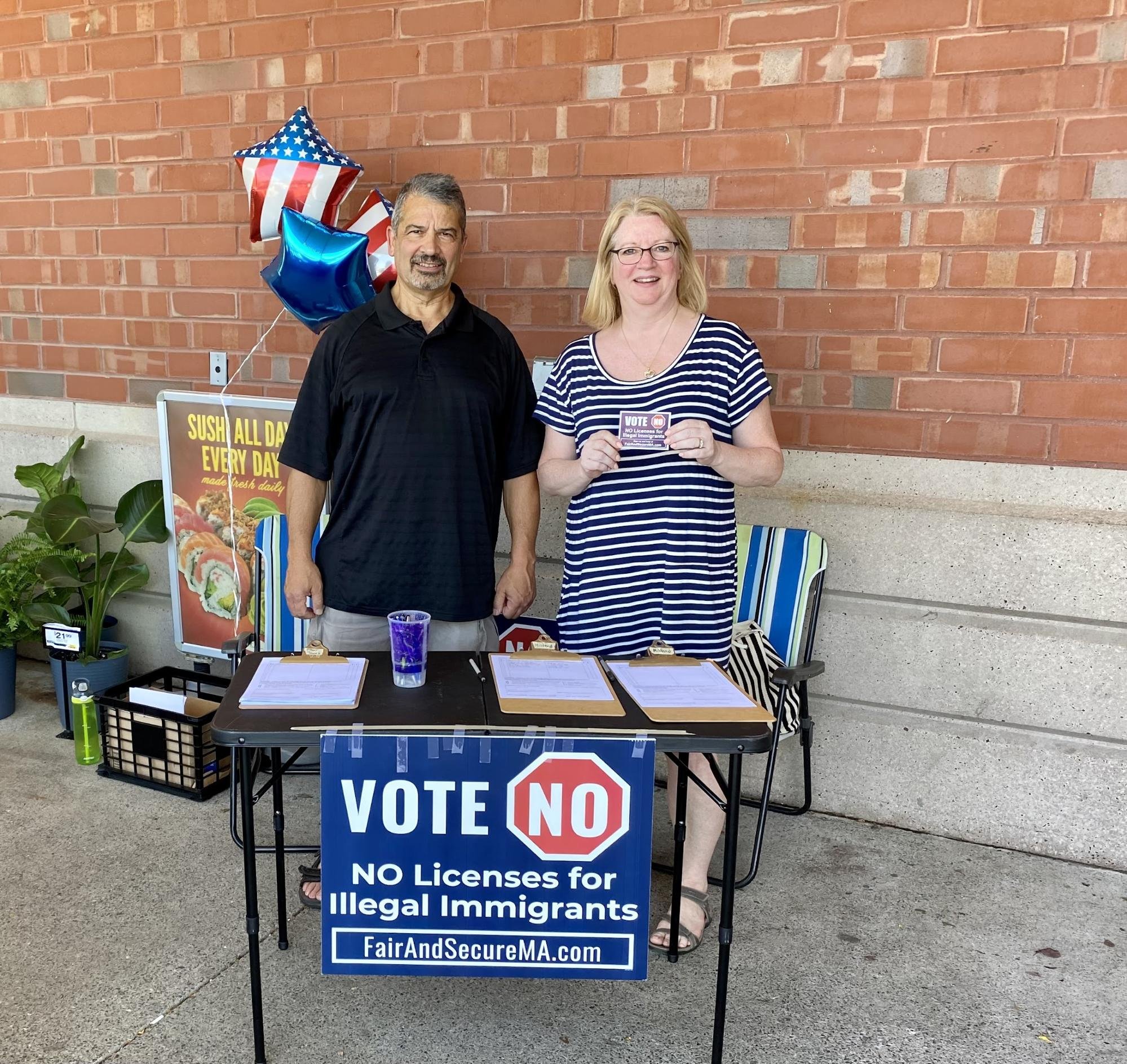

Maureen Maloney (right) promotes the efforts to repeal a state law to grant driver’s licenses to undocumented immigrants. Photo courtesy Maureen Maloney.

Unlicensed drivers have caused accidents, including serious ones. A September 2015 article by the Pew Charitable Trusts noted multiple surveys of accidents committed by unlicensed drivers, although it did not specify whether these drivers were undocumented.

Maureen Maloney, the organizer of the initiative to repeal the Massachusetts law, became personally involved in the debate after her son, Matthew Denice, was killed by a drunk driver who happened to be an undocumented immigrant in a 2011 motor vehicle accident. The driver ran through a stop sign and collided with Denice, who was 23 years old.

Maloney is the head of a group called Fair and Secure Massachusetts, which worked with the state Republican Party on a successful petition drive to get a repeal question on the election ballot. “Had our laws been enforced, my son would still be alive,” Maloney said.

In 2014, a National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) research note found that from 2008 to 2012, there were at least 5,800 fatalities each year in motor vehicle accidents involving drivers whose license was invalid — a term that included having no license at all. The research note did not specify how many of these drivers were undocumented immigrants.

Maloney also questioned whether the new Massachusetts law could be used for fraud, citing the passage in 2020 of a state motor voter law that automatically adds driver’s license applicants to the voter rolls.

“Aside from the voter concerns about who would be registered to vote, giving them a valid form of ID tasks the Registry of Motor Vehicles (the agency that issues driver’s licenses in Massachusetts) with identifying foreign documents for authentication,” she said. “I don’t think it’s fair to RMV workers. I don’t think they have adequate training to take on a task where a lot of fraud is identified around this issue.”

Supporters of the law deny that it can be used for voter fraud.

“Only U.S. citizens can vote,” Reason said. “You have to be born here, or naturalized here. A license is not going to allow anybody to vote. We have to educate voters about this.”

Although Montalva Barba is now a licensed Massachusetts driver, he is keeping an eye on where things stand for undocumented immigrants in his adopted home state.

“I remember hearing about Massachusetts calling for driver’s licenses for all back when I was still in California,” he recalls. “I remember thinking how revolutionary this was … to see it pass after having struggled so long was a huge and beautiful victory.” Yet, he adds, “to see it back on the ballot was really disheartening in many ways.”

—

Rich Tenorio is a writer and editor whose work has appeared in international, national, regional, and local media outlets. He is a graduate of Harvard College and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. He is also a cartoonist.