A Clash of Two Lives

Leonor Gomez wasn’t prepared to become an activist fighting two battles at the same time. One was aimed at stopping her husband’s deportation, the other was to prove his innocence for alleged crimes he committed decades ago in Guatemala. July 12, 2022 Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

Almost 40 years after a tragic civil war in Guatemala, the collateral damage continues. Two families - two communities - today have widely different visions of one man

Editor’s note: This story spans two very different moments in recent Latin American and United States history. One moment is tainted by the shadow of a U.S.-backed dictatorship in Guatemala whose security forces authored violent destruction and left collective grief and open wounds for generations of families of people who died or disappeared. The other moment is now – as U.S. immigration detention continues to serve as a heavy tool behind an asylum process that has become a dehumanizing nightmare for applicants, many from countries like Guatemala.

Photojournalist Zaydee Sanchez was reporting on a hunger strike outside the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) office in downtown Los Angeles, led by women advocating for the release of immigrants during the pandemic. What she thought was a story of activism and struggle quickly took a deeper turn. Partnering with writer Abraham Márquez, the duo reported with care, humanity and empathy on the lives of two families seeking justice, from two sides of a tragic episode in Latin American history. Sanchez and Márquez also shine a light on an obscure corner of international government operations that moves slow or fast, depending on prevailing political winds.

For families and friends of the disappeared in Guatemala this story will inevitably be triggering. We shadow the plight of one woman to stop the deportation of her husband accused of a violent crime, and we meet another coming to peace with the past as those involved in the disappearance of her husband are held accountable.

But their struggles are not their own; their causes transcend individual narratives. Their stories cast light on major human rights violations, which we’re not trying to compare or balance against one another. Without diminishing the historical weight of violence and repression that occurred in Guatemala, the bulk of this story happens here in the U.S., where we zoom into the pitfalls of the deportation system as it affects the future of countless humans.

The deportation machine in this country puts the burden on people to prove to authorities that they shouldn’t be deported. Much has been written about how that system intersects with criminal justice. Those caught in the crosshairs of these bureaucracies pay a steep price, often in proceedings that lack the kind of due process we believe every detained person is supposed to get in this country.

There hasn’t been enough deep reporting on what happens to that due process when vested interests in two countries come together and alter one person’s future. Even more rare is reporting that centers families’ perspectives about struggles for justice that cross borders and time.

This is why palabra is telling this story now.

—Valeria Fernández, palabra’s managing editor

“I don’t know, and I just don’t know anymore, I don’t know what to do,” Leonor Gomez says, holding her hands tightly as she waits by the telephone. She’s tired and her voice is soft. Yet a sense of fortitude is clear: She’s thinking it all through as she gazes at the family pictures on the walls of her modest home in Hawthorne, an urban community just south of Los Angeles International Airport. She sits up in her living room’s white accent chair, a poised petite woman dressed in homely clothes, as she twists her wedding ring around her finger.

The next call, she adds, is sure to come from her husband.

When it does, it will come from the Adelanto Immigration and Customs Enforcement Processing Center, a detention facility run by the private, for-profit GEO Group, an ICE contractor. For two and a half years, Hugo Rolando Gomez Osorio has been detained there, among hundreds of other individuals waiting for immigration court or destined for deportation. The Adelanto facility is about 90 miles northeast of Los Angeles in Southern California’s High Desert.

In the summer of 2019, Leonor launched her crusade against arbitrary immigration and customs detentions of legal residents like Hugo – someone who had also spent years helping his community as a respected evangelical preacher.

But to Leonor’s surprise, and the shock of a large community of religious and civic supporters in suburban Los Angeles, Hugo was detained and sent to Adelanto at the request of law enforcement officials in two countries who suspect he was involved in a crime committed in the late 1980s, when Guatemala’s long and bloody civil war was at its peak.

The crime was the disappearance of a well-known activist. Documents suggest Hugo, who once worked for Guatemala’s national police, was one of four officers involved in the disappearance of the activist Edgar Fernando García, who has never been seen again. Two of the officers have been convicted, but Hugo – through Leonor and a vocal community of friends, lawyers and immigration activists – insists the documents unearthed by the investigative non-profit, National Security Archive, are wrong. He’s fought to at least temporarily hold off his deportation to face charges in Guatemala, arguing the international system of Interpol Red Notices is flawed and allowed authorities in his native country to seek his arrest based on bad evidence collected during a chaotic period of war.

That war remains a raw nerve for many Guatemalans, which is why the discovery, in 2005, of decades-old military documents reopened psychological wounds for many families in the Central American nation, and in cities in the United States that are now home to the Guatemalan diaspora.

For Leonor Gomez, the appearance of the family name in those documents ignited a historical and political nightmare.

Leonor Gomez holds a portrait of her husband of 40 years, Hugo Rolando Gomez, who was detained by ICE outside their home on August 16, 2019. July 12, 2022. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

“I’ve delivered food for Instacart to make extra money,” Leonor says, running through the hardships she’s endured since Hugo Gomez’s apprehension. She’s short on cash, and faces mounds of legal paperwork stacked up on the dining room table in her tidy home.

When Hugo lost his freedom, he left the management of a landscaping business he had owned for decades in the hands of his daughter, Debbie, who is also a nursing student.

The family’s spiritual well-being was left to Iglesia de Cristo, Lluvias de Paz, the evangelical church in Hawthorne that the couple has led as pastors. Hugo and Leonor count on a strong group of church members who now help maintain the church in Hugo’s absence.

“Our church community is always checking in on my family and me,” Leonor says.

“At every service, people are always telling me they miss him.”

Though Hugo’s absence is felt by the family and its tight-knit community, Leonor says she’s tried to keep their home as a familiar sanctuary, ready for his return. There’s a keyboard in the family room and Leonor and Debbie make time to sing duets. Scattered around the kitchen are healthy food recipes, guides for the new memories mother and daughter are trying to make. The rooms upstairs are filled with family pictures, highlighted by sunlight filtered through white curtains on the windows.

Debbie participates in a sack race game during a pre-Fourth of July church service. The church tries to keep Sunday worship as entertaining as possible for the youth by holding service in a park and providing fun activities. July 3, 2022. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for Palabra.

As hard as she’s worked to make this new life seem normal, Leonor is improvising. It’s the first time she’s lived apart from Hugo. She says she fears the prospect of being away from him for a long time.

ICE says it is holding Hugo on behalf of Guatemalan authorities who want him to face trial for allegedly taking part – when he was a federal police officer – in a forced disappearance of a political dissident. The U.S. government also wants to deport him for allegedly lying on his asylum application, according to immigration court documents.

“Alan (Diamante, one of the Gomez family’s attorneys in the U.S) said this has something to do with more than immigration,” Leonor adds, opening a door to a series of conversations she’s had with palabra over the course of about two years. In that time, she’s gone over not just the impact of Hugo’s detention, but her outrage about the charges in Guatemala, and how this episode, she says, has left him seriously ill.

“Since August 2019, he’s been detained, he turned 60 and 61 behind bars, he tested positive for COVID and was not released,” says Diamante, who insists Guatemalans are pursuing the wrong man.

“They are turning my husband’s case into a political one,” Leonor adds.

Hugo’s past has him in the crosshairs of authorities in both countries. He faces fights for his future in two nations, nearly 3,000 miles apart.

Years after the protracted and bloody civil war ended, families in Guatemala and the United States continue to seek answers to what happened to many loved ones. Years later, shock waves still separate families.

Hugo’s story hits the heart of generational trauma that a lot of people are still working through. Almost four decades later, it’s as if an emotional and psychological war continues to be waged. In the middle is a man many people say they know, but for widely divergent reasons.

Inside their home, Debbie helps Leonor look through Hugo’s medical records. July 12, 2022. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra.

Hugo in Los Angeles

Pastor Hugo Gomez worked hard to earn a faithful following in his adopted Southern California community. After decades of sermons and helping church members get through all manner of crises, they say Hugo is a holy and honest man who preaches the Lord’s word, a genuine religious example for his church.

In Guatemala, human rights advocates say they know him for something completely different.

Long before he was a pastor in the U.S., Hugo worked for the National Police of Guatemala. Government files show that during his time in uniform, he was a police officer for what documents and witness testimony describe as a repressive government backed by the United States. His work during Guatemala’s civil war is years and many miles apart from the life he has lived in the U.S. since 1987.

Hugo Rolando Gomez Osorio is a 62-year-old Guatemalan citizen and a legal U.S. resident. He is a father to three daughters. He is a grandfather.

Hugo served his community as a pastor for more than three decades. Now, that community has turned militant on his behalf. Church members have joined Leonor in a fight to prevent Hugo’s extradition, to win his release and restore his reputation.

Leonor leads Sunday church service at the Iglesia de Cristo Lluvias de Paz in Hawthorne, California. July 10, 2022. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra.

Leonor spells out Hugo’s tireless work for his church: Even in detention, he continues to counsel individuals struggling with drug and alcohol addiction. (Hugo is certified by the Association of Christian Alcohol and Drug Counselors Institute.)

“They call me regularly to ask if he is out yet,” Leonor says, turning again to her phone to see if there are any new messages from church members or Hugo’s lawyers. Before the accusations against Hugo became public, hundreds of people were part of their church family, Leonor says. But once the media began covering Hugo’s case, they lost a significant number of church members. “It was very difficult. The names they would call my husband were painful. Debbie, she encountered so much hate from some.”

“Hugo was always there for people,” says Noemi Maravilla, a volunteer at their church, on how he impacted people’s lives. “He’s a respectable man people looked to for receiving advice,” adds Marcos Altieri, a church member, and family friend.

As Debbie preaches to the congregation, Leonor closes her eyes in prayer. Throughout Hugo’s detention Leonor says her faith has kept her going. July 10, 2022. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

Hugo does all this, Leonor adds, even as he fights off lingering effects of a coronavirus infection. ICE reports that nearly 300 individuals detained at one point at Adelanto during the pandemic tested positive for COVID between February 2020 and the publication of this article. Advocates believe the actual number is probably considerably higher. Hugo tested positive after a federal judge ordered a reduction in the Adelanto ICE Processing Center population from 772 to 475 to reduce the spread of the deadly virus. However, when authorities began releasing people, Hugo’s name was never called.

Meanwhile, medical records show Hugo has also developed a tumor. ICE has not responded to inquiries about whether this is a condition that emerged while in detention. Leonor says the condition is affecting his vision. “I worry for him…. He doesn’t receive the medical treatment he needs in there.”

In a recent letter by Hugo to the Inland Coalition for Immigrant Justice, he said he is also experiencing blood in his stool.

When palabra asked ICE about the care Hugo was receiving, they sent a generic statement via email: “U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) takes very seriously the health, safety, and welfare of those in our care, including those who come into ICE custody with prior medical conditions or who have never before received appropriate medical evaluation or care. ICE is committed to ensuring that everyone in our custody receives timely access to medical services and treatment.”

Inside her living room, Leonor speaks to Hugo on the phone from Adelanto Detention Center. Since Hugo has been detained, the couple speaks at least twice a day. April 8, 2021. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

Leonor the activist

Leonor Gomez spent 30 years of her life as a loving mother, wife, and more recently, a grandmother. Now, she’s also an immigrant rights activist.

In October 2020, in the middle of an unseasonable warm week and pandemic, she joined mothers and families engaged in a hunger strike for five days in front of ICE Los Angeles Field Office, located downtown in the Federal Building. The SoCal Region Presbyterian Immigration and Refugee Task Force and Freedom for Immigrants organization joined them. Over five days, she lived on the streets, brushing her teeth outdoors, near where she slept.

Immigration rights activism can be a frustrating and demanding role. Day to day, Leonor has found new ways to advocate for her husband’s freedom. It’s an emotional drain on her and her daughters, she says, having clocked countless hours driving to Adelanto to attend speak-outs and protests where families have called for the release of loved ones held by ICE.

At an immigration rally outside the Adelanto Detention Center, Leonor drives up and down the road as Debbie screams out, “Release my dad.” October 24, 2021. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

Leonor has never been shy about speaking her mind: In the 1980s, in Guatemala, she believed in the work of former army general and self-proclaimed President Efraín Ríos Montt, who, along with a group of army officers, seized power in a military coup d’état and ruled the country as the leader of a military junta. The move was praised by then U.S. president Ronald Reagan. “Guatemala suffered, but it rested when Ríos Montt took office,” she says.

“As a child, I somewhat understood what was happening, but it was also just part of our daily life,” she adds, reflecting on growing up in the middle of the civil war and learning, for example, what parts of the city were considered safe.

The war between guerilla forces and the government was decades-long, but Leonor says her family felt at peace when Ríos Montt was in office.

And, amid the bloody conflict, Leonor and Hugo met and fell in love.

Leonor embraces Debbie on the second day of the hunger strike outside the Immigration Service office in downtown Los Angeles. October 3, 2020. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

Hugo in Guatemala

“I was on the bus in the district called ‘La Reforma’ when he (Hugo) got on,” Leonor says, blushing a bit and clasping her hands as she smiled and then remembered their first meeting. “When the lady next to me left, that is when he sat next to me. He later gave up his seat to an older lady; I said, ‘Wow, what a gentleman.’”

She recalls that the bus ride allowed Hugo to get to know Leonor and work up the courage to ask if they could see each other again. “That’s when we started talking, and have not stopped since.” Leonor pauses, gathering herself, and returns to the present: Even today, while he’s detained, she said she and Hugo can talk for hours.

By 1981, civil strife was thick in Guatemala. That same year, Leonor and Hugo learned that she was pregnant with their first child. “He was so excited, we celebrated the news with friends and family,” she says.

The violence in Guatemala, however, kept interrupting their new life. At nights and weekends, Hugo sang at parties and in clubs. But his steady income was earned in a factory that made parts for airplanes. He was devastated when he was let go in a company layoff. “His singing was not enough,” Leonor says. “His brother advised him to apply to the police department because they were hiring.”

Police station at Colonia Bethania, Zona 7, in Guatemala City. The police station is where Leonor says Hugo worked in the late 80s. July 13, 2021. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

On September 1, 1981, Hugo became an official member of the National Police. The following months were harrowing, Leonor recalls. She remembers two incidents where Hugo was mistakenly listed as having been killed in the line of duty. “I felt cold, and I felt my stomach paralyzsed.”

Despite the anxiety, in 1982, Leonor gave birth to their first daughter. “Hugo celebrated all night when she was born; he was so happy,” Leonor remembers.

But the happiness ended in 1986 when Hugo was fired. Leonor recounts that he was dismissed for not being at his post. (Immigration court filings obtained through a FOIA request indicate that the reason for his dismissal was drinking on the job.) Sudden unemployment was a shock to the couple and their young family. So while the country was under a dictatorship they migrated north. “We always talked about moving to the United States,” Leonor says.

On or about July 4, 1987, as Americans celebrated their Independence holiday week, the Gomez family entered the U.S., crossing the border without documents. They joined a river of Guatemalans fleeing the civil war. The number of people fleeing the country rose from 13,785 in 1977 to 45,917 by 1989, the peak of the war. When the Peace Accords were signed in 1996, it had dropped back down to 22,081. In these numbers, there was a mixture of people fleeing. A majority were victims of state repression. Others were those doing the repression.

Leonor’s home is surrounded by family pictures of her daughters, grandchildren and Hugo. July 12, 2022. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra.

In their early days in the U.S., Leonor says, she’d start each day taking her girls to school and then heading to work as a housekeeper.

Leonor fought back tears as she recalled the family’s early hardship in the suburbs of Los Angeles. Hugo and Leonor had arrived with nothing but hopes and dreams, she says. “We placed our lives in God’s hands,” and that was followed by Hugo landing a gardening route, and then becoming the owner of a landscaping business.

On December 11, 2003, the blessings continued as Hugo obtained U.S. residency under The Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA). The policy allowed certain Guatemalans, Salvadorans, and Nicaraguans fleeing political instability in the 1980s to seek asylum and reside legally in the U.S.

The Guatemalan reality

As the Gomez family became a part of the fabric of the Los Angeles community, Guatemala was embarking on a long reckoning.

Repression of popular movements and indigenous people had been a key feature in a Guatemalan revolution, from 1944 to 1954, that brought radical land and social reforms.

In 1952, indigenous people were the primary beneficiaries of Decree 900, also known as the Agrarian Reform Law, initiated by President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. This law gave Guatemalans land back by expropriating the unused property of the United Fruit Company, which for many years had owned as much as 42% of Guatemala’s countryside and was the nation’s largest private landowner. The company controlled the economy and was “exempted from paying taxes and import duties,” as stated in a report by the Baltimore History Labs Project and the University of Maryland.

President Árbenz’s reforms were popular among Guatemalans, but unwelcome in Washington, D.C.

Former Guatemalan dictator, Efrain Ríos Montt, during the genocide trial at the Supreme Court of Justice in Guatemala City. March 19, 2013. Photo by Hiroko Tanaka via Shutterstock

Allen Dulles, director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and his brother John Foster Dulles, then U.S. secretary of state, owned shares of the United Fruit Company. The result was a U.S.-trained and backed army invading from Honduras to overthrow Árbenz. What followed was a reversal of all of Árbenz’s progressive measures and an intense class and cultural conflict.

The internal war reached a new level in the 1980s. Ríos Montt, a graduate of the notorious School of the Americas (currently the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation), a U.S. training center for allied foreign military officers, seized power following a coup d’état in 1982. During his rule, local defense units terrorized rural indigenous regions of the country, chasing after dissidents and guerrillas. Ríos Montt was later ousted by another military general, Óscar Humberto Mejía Víctores, who continued the violent repression of political dissent and anyone deemed sympathetic to an out-gunned but persistent insurgency.

At this time, Colonel Héctor Rafael Bol de la Cruz, director of the National Police, was at the forefront of the government’s urban campaign. He supervised the operation leading the disappearance of Edgar Fernando García. Years later, Bol de la Cruz would be convicted and sentenced to 40 years in prison for his role in the kidnapping.

Bol de la Cruz spent most of his career in counterintelligence. He earned the respect of his superiors for helping “exterminate” the Organization of the People in Arms (ORPA), which included urban dissidents and members of Guatemala’s indigenous Mayan communities.

The monument to peace stands in the center of Guatemala City, a symbol of a peace treaty to end Guatemala’s civil war. June 15, 2021. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

In 2011, the Guatemalan courts charged Mejía Víctores with crimes against humanity. Due to his poor health – he was physically and mentally unable to stand trial – “public prosecutors were forced to drop an indictment,” according to a document from the National Security Archive, a Washington, D.C.- based nonprofit research organization founded in 1985 to investigate and expose once-secret government documents. Five years later, he died at the age of 85. In 2012, a Guatemalan court charged General Efraín Ríos Montt with genocide after reviewing ample evidence of “killing thousands of indigenous Guatemalans by soldiers under his command,” according to the NSA document.

In 2013, the Guatemalan government convicted Bol de la Cruz for his role in the 1984 forced disappearance of García, a student and labor organizer and one of an estimated 45,000 forced disappearances during Guatemala’s civil strife. García is believed to be among the 200,000 civilian lives that international human rights experts report were lost in the civil war.

From August 8, 1983, to April 30, 1984, a total of 635 cases of forced disappearance were reported, an average of 80 per month.

Professor Alejandro Villalpando. Photo courtesy of Villalpando

“To understand the violence Guatemalans experienced in the 80s, you have to look at how the U.S. trained and funded these forces starting in the 1960s,” says Dr. Alejandro Villalpando, professor of Pan African Studies and Latin American Studies at California State University, Los Angeles.

Today, the thousands of activists, students, and indigenous people who disappeared are honored by memorials throughout Guatemala—including one at the historic Catedral Metropolitana de Santiago de Guatemala, an ornate landmark that for centuries has marked the center of the city. Guarding the church entrance and the constant masses celebrated inside the vast nave, stone pillars hold the names of the disappeared, listed in alphabetical order.

Another memorial, at the University of San Carlos, is a wall dedicated to victims of the civil war and includes García’s name. A third plaque in Guatemala City also bears his name, this one at a small private school near the offices of Grupo de Apoyo Mutual – the Mutual Aid Group, known as GAM – an organization still seeking justice for official crimes committed during the civil war.

Names of those disappeared during Guatemala’s bloody war are engraved on the church pillars of the Catedral Metropolitana de Santiago de Guatemala. June 16, 2021. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

A blast from the past

In the early 2000s, “we were happy, me as a mom, and Hugo as a father, my daughters, we regularly went to church as a family,” Leonor says. Their security as U.S. permanent residents, not only provided a feeling of freedom for the family, but brought them one step closer to U.S. citizenship. It gave them a sense of belonging and joy, Leonor says. Hugo was finally able to go back to Guatemala and visit his parents. “We celebrated our 26th wedding anniversary there” and partied with family.

But in July of 2005, the past roared back into Hugo’s and Leonor’s lives: an explosion damaged an old police warehouse in Guatemala City. In the clean-up, government inspectors found explosive documents – historical archives of the National Police, papers that authorities for years had said did not exist. The building had been a base for a police unit said to be tied to Ríos Montt.

The documents yielded names of those allegedly involved in forced disappearances. Notably, Hugo Gomez’s name appears among four arresting officers in documents that have been tied to the arrests of Edgar Fernando García and Danilo Chinchilla.

The authenticity of these documents has been brought into question by Leonor and Hugo’s attorney. They’ve argued in immigration court that the documents were fabricated.

"February 18, 1984, at 11:00 AM, while conducting an operation in the Mercado de Guarda in Zone 11, were attacked by two subversives, from whom they confiscated subversive propaganda and firearms" reads a National Police document listing officers, including Gomez, who were to be decorated for acts of valor.

During the apprehension, Chinchilla was shot in his left leg and rushed to the hospital by security agents. Colleagues of the Guatemala Labor Party then organized his rescue from the hospital several days later. A tape of Chinchilla describing García’s kidnapping was later played in a courtroom. National Security Archive documents relate that seven months after his escape, Chinchilla was captured and disappeared by security forces.

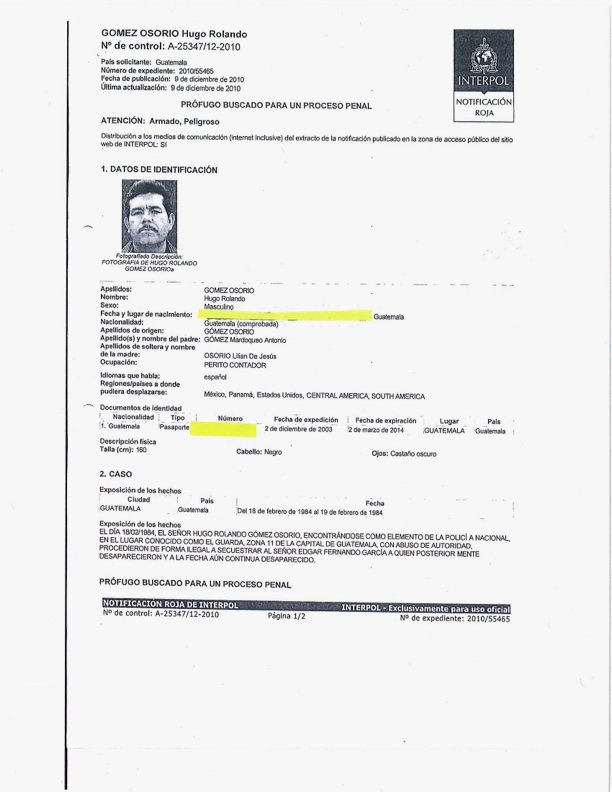

The discovery of the long-lost police records and Chinchilla’s tape led to the conviction of two of the former officers, and later, to Interpol’s issuing a Red Notice on behalf of the Guatemalan government for Hugo Rolando Gomez Osorio.

Who was Edgar Fernando García?

Edgar Fernando García was an activist leader in the clandestine Guatemala Workers’ Party (PGT). He was also an engineering student at the University of San Carlos – a campus identified by the government as an ideological center for “subversion.”

The school had become a constant “focus of intense governmental interest and attention regarding counterinsurgency activities,” according to an Inter-American Commission on Human Rights report. Professors, students, and workers of the university who displayed sympathy, or were believed to be involved with insurgents, were monitored. Many were detained and tortured.

García was an advisor to the university’s Labor Orientation School – reason enough for him to be targeted by Guatemalan officials working with the CIA, reports the Guatemala Human Rights Commission. National Security Archive documents show that National Police had been documenting García’s life since 1977, seven years before he was detained.

García was last seen in the custody of the National Police and today he’s thought to be dead.

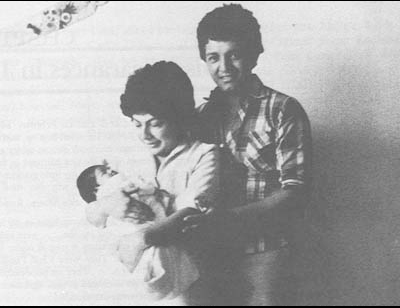

When García disappeared, he left behind his wife, Nineth Montenegro, and then 18-month-old daughter, Alejandra García.

Edgar Fernando García with his wife Nineth Montenegro and daughter, Alejandra García. Photo National Security Archive

A Love Lost

“We met in 1979, began dating in 1980, and we fell in love,” Nineth Montenegro says, smiling and looking off to a distant memory of how she met Edgar Fernando García, or 'Fernando,' as he was called by loved ones. The two had a lot in common; community organizing and a passion for social justice that called out the sins of the government and its foreign supporters. In May of 1980, they married and committed to a life of social activism. “He was sweet and very loving. It was something I didn’t realize I needed in my life,” says Nineth, as a summer rain begins to drizzle on the patio roof of her home in Guatemala City.

She has been living in a security-gated community for some time. Green trees with vast leaves spread out around the garden. A small waterfall takes on the water drops from the storm as Nineth speaks. There is a calmness to her, a sense of stillness when recalling the past. Her small figure is wrapped in a red poncho.

Nineth’s eyes begin to shine as she starts to talk about Fernando with full clarity. It was a love never to be forgotten, she says.

Nineth Montenegro in her home in Guatemala City. Montenegro was elected to Congress in 1996. June 21, 2021. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

Student involvement in the fight for justice was not uncommon at the University of San Carlos. “We saw that there was a lot of social unrest from injustice people were receiving, almost impossible to live in Guatemala,” Nineth says, remembering that Fernando agreed with her that they needed to be involved, as dissidents, in order to fix the country’s ills.

Three years after they met, in 1982, Nineth gave birth to their first child, Alejandra. “Fernando was a sweet and loving father to her,” Nineth says.

Their new family life at home was joyful, Nineth recalls, even as the couple was keenly aware of the growing state repression on the streets around them. The contrast terrified her. “I got to a point where I told Fernando, let’s move to Mexico, it is not safe here.” Fernando did not like that idea, reiterating that he was committed to making a difference in his country. He was deeply involved in organizing, Nineth adds.

The social conflict intensified. What followed was “the reign of terror,” during which “the Guatemalan army carried out 77 massacres in the Ixil-Ixcan region,” according to Victoria Sanford, an anthropology professor at City University of New York and director of the Center for Human Rights and Peace Studies at Lehman College. “There are 3,102 known victims of these massacres” led by dictator Efraín Ríos Montt and his “death squads.”

The suppression of social movements was also hitting home for Fernando and Nineth.

After a year as parents, Fernando finally agreed with Nineth: They would move to Mexico. “Let’s go take our pictures to get our passports for all three of us,” she recalls Fernando saying in early 1984.

‘I felt alone in this fight’

Nineth says Fernando wanted to provide for his family and saw himself doing that in Mexico, which had emerged as a safe haven for political refugees fleeing official repression around Latin America. With fighting in Guatemala getting worse, “I was relieved he finally said yes,” Nineth recalls.

On the night of February 17, 1984, a few short weeks after they’d decided to start their move to Mexico, Fernando told Nineth he needed to leave early the following day to attend an event. “I started crying; something didn’t feel right,” Nineth says, her voice cracking before she pauses and apologizes: revisiting that specific day is still difficult. It was the night everything changed, she says.

Nineth recalls her quick reminder to Fernando: They had a family gathering on Saturday that they were obliged to attend. Fernando said he would meet her there by lunchtime. But lunch came and went, and he hadn’t appeared, and Nineth knew something bad had happened. “Something happened to Fernando, I told my sister-in-law.”

Nineth recalls telling María Emilia García, Fernando’s mother, “It’s 7 pm. He’s not back.”

But instead of shrinking and going into hiding, Nineth mobilized everything she could to search for Fernando. “When I realized he was kidnapped, I lost all fear. I felt indignation. Nothing is going to stop me.”

During the search, Nineth visited the area where Fernando had last been seen. In the investigation it is recorded that Fernando was not alone that day. Danilo Chinchilla, was with him when both men were captured in Guatemala City’s Zone 11, a hilly area six miles southwest of downtown. Today Zone 11 is a busy, middle-class neighborhood. Four decades ago, when Nineth was searching for Fernando, there were no markets or rows of colorfully painted homes lining the streets. Back then, “I felt I was losing everything I loved.”

“At first, I felt alone in this fight,” Nineth says.

Looking back on what she described as a frightening, fruitless search for Fernando, Nineth says she instead found something new: a community that, like her, was tested by tragedy and made stronger by testing the country’s government. She and her new friends went into morgues, secret cemeteries, and attended clandestine memorials where families made sure that time would not erase memories of the dead or missing.

Today’s 7th Street and 3rd Avenue, Zone 11 in Guatemala City, the area where Edgar Fernando García was last seen, according to the National Security Archive. June 16, 2021. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

At least half of Guatemala’s population is of Maya descent. Maya and Maya descendants believe in an afterlife, and that it’s up to the families to guide lost loved ones. They believe that souls need sustenance for the journey. But for their disappeared, the important cultural practice of a proper burial, of leaving some maíz in the mouth of the deceased as a symbol of rebirth, was denied to them.

Nineth says she noticed the same women at every place she visited during her search for Fernando. She befriended them, and in 1984 they formed the Grupo de Apoyo Mutuo - the Mutual Aid Group - to provide support for families of civil war victims. The group grew in numbers and in reputation, and in 1986 they were nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

“I realized there were thousands of women in rural communities, indigenous women; who were experiencing the same pain and suffering I was,” Nineth says. The struggle of the rural and indigenous women caught the attention of activists in the cities. “When they heard of what we were doing, they joined by the thousands.”

GAM’s support grew each year as the civil conflict showed no signs of ending. As its profile grew, so did the volume of criticism from the government and the political right. Once, the reaction was a violent attack on its headquarters. But that did not stop Nineth or GAM.

In 1992, Nineth, along with other women who worked for human rights and peace in Guatemala, was part of the Nobel Peace Prize exhibit in honor of Rigoberta Menchú, the first Guatemalan and indigenous recipient of the award. In 1996, Nineth was elected to Congress. Later that year, peace accords were signed to break up the thirty-six-year combat between guerrilla forces and the government.

Nineth ties those accords to the work of activists like Fernando. “Today’s civil peace is a result of the past movements. People sacrificed a lot for this to happen.”

Nobel prize-winner and presidential candidate Rigoberta Menchú (center) is greeted by supporters during the close of her presidential campaign in Guatemala City. With Menchu is vice-presidential candidate Luis Fernando Montenegro (left) and then congressional candidate Nineth Montenegro. August 26, 2007. Photo by REUTERS/Carlos Duarte via Alamy

Two Worlds Collide

In the morning hours of August 16, 2019 – a Friday – “(Hugo) told me not to get up early and to get extra rest, and I did,” Leonor says. When she finally did get out of bed, and began her morning routine of brushing her teeth, fixing her hair, and applying a modest dose of make-up, she noticed a missed call from Hugo. “I said to myself I would call him later,” Leonor says, instinctively grabbing a tissue in case her attempt to hold back tears fails. But then came the call that brought her life to a standstill: “Honey, I’ve been arrested,” Leonor recalls Hugo saying.

“I wanted to at least see him.”

Leonor gathered herself and took a deep breath. She called Alan Diamante and told him that immigration took Hugo. At the time, Diamante didn’t know the whole story about Hugo, says Leonor. When she arrived at his office she told him everything. Later, Diamante learned that Hugo was already taken to the Adelanto ICE Processing Center and informed Leonor and Debbie. It was a quick operation, she says.

The agonizing pain of her husband’s detention was not something Leonor could have prepared for. But upon learning more about the detention, she knew she would have to be strong, for her family and for her husband.

“I felt disoriented; I didn’t know what to think,” adds Debbie, Gomez’s youngest daughter, who says she has since battled depression.

On the morning of the third day of the hunger strike, Leonor and Debbie begin to feel more and more tired. In this moment, mother and daughter sit on the sidewalk holding each other. October 4, 2020. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

Diamante told them in his office that Hugo’s detention was not about immigration, but was related to the Interpol Red Notice requested by Guatemalan authorities on March 2, 2009.

In addition to the Interpol notice, the Department of Homeland Security contends that Hugo “misrepresent(ed) a material fact” in his NACARA application, when he applied for immigration status, by not disclosing his involvement in persecuting an individual because of their social group or political opinion. It is an argument Hugo opposes, as he has denied any involvement in García’s disappearance.

The revelation from the 2005 explosion unlocked an extensive cache of documents, adding details to cases of human rights violations from 1960 to 1996. These documents led to a deeper investigation by the National Security Archive, and then by human rights advocates in the Guatemalan government.

In 2009, “my sister called me to tell me to leave the house and to call her from a different number,” Leonor recalls. The shock of that call engulfed her, but she nonetheless followed the instructions. Unaware of what would happen next, she walked over to her neighbor and redialed her family in San Francisco. Leonor learned that Hugo’s name was circulating and that prosecutors were demanding his extradition.

“I thought my sister was crazy, so I asked her if she ate breakfast,” Leonor says. Her next call was to Hugo, who downplayed the news.

”He said everything would be okay. ‘I’m not worried, I didn’t do anything.’”

Then, on October 28, 2010, two of the four ex-members of the National Police who were seen with García before he disappeared were sentenced to 40 years in prison.

By the time of that trial, Alejandra García, daughter of Edgar Fernando García, was an attorney and had joined the government’s prosecution team and “affirmed that they have over 550 documents from the archives of the National Police.” Fernando’s case was the first to lead to convictions after the old police warehouse explosion and the discovery of the trove of documents.

Peace and Reconciliation?

“I will never, never, never forget the man of my life, the father of my first daughter,” Nineth says.

Yet, she adds, “I have no hate or anger in my heart.”

Nineth is remarried. Her husband is Mario Polanco, now the National Director of GAM.

“I am not the one who is going after the remaining officers,” Nineth adds. She calmly describes how it’s the Guatemalan government’s justice department that’s following up on all the documents found in the damaged warehouse and has since been published by the nonprofit National Security Archive. “My daughter retired from being a lawyer. She is (now) taking care of her health,” she says. “I am at peace.”

Edgar Fernando García’s name is engraved on one of the pillars outside the Catedral Metropolitana de Santiago de Guatemala in Guatemala City. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

But thousands of miles and a world away in Los Angeles, Leonor continues fighting for her husband’s release.

“If they want him handcuffed, have him cuffed in my house, but we want the opportunity for due process,” Leonor says.

Recently, Leonor filed a lawsuit in Guatemala against Nineth Montenegro, Mario Polanco, and the founders and representatives of GAM, alleging illicit association, conspiracy, and abuse of power, without adding further details. When palabra contacted Nineth about the lawsuit, she said she sees no sense behind it. “They use my name to give another connotation to the case.”

More than 30 immigation and human rights coalitions have joined Leonor in advocating for her husband's release. Los Angeles human and immigration rights faith based organization, Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice, leads the movement. The group has demanded Hugo be released, claiming the possibility of new evidence that criminal actions that were ‘prefabricated’ against him.

While Hugo awaits the outcome of his wife’s advocacy and his lawyer’s work in Guatemala, he’s also preparing for another challenge in the U.S.

When he and Leonor applied for U.S. citizenship in 2009, they received no response. “They never called,” says Leonor. Over a year later, the Interpol Red Notice followed Hugo. She says she never heard about the notice. Leonor and the family’s attorneys question why it took a decade for authorities to find a man who had been very public and known to his friends, family, and church congregants. It’s a question that, after several inquiries by palabra, ICE hasn’t answered.

The only explanation that ICE has publicly provided is that the pastor was arrested because he was the subject of an active Red Notice, according to Alexx Pons, an ICE spokesperson. An immigration judge ordered Hugo’s deportation in February 2021, and Hugo’s attorneys appealed that decision. That appeal was denied, so in July, 2021 his lawyers asked the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals to review the case. A decision is pending.

But his legal team continues to fight. “I’m asking they delete the Interpol Notice or provide the documents that Guatemala submitted in our case,” says Monia Ghacha, one of two attorneys in the U.S. now representing Hugo. In August 2021, she filed a challenge to the Commission for the Control of Files (CCF) for Interpol in France. In a response earlier this year, the commission said it will temporarily block the Red Notice pending a review of the documentation in Hugo’s case.

For Hugo’s attorney Ghacha, this means her client should be released. In a letter to ICE demanding Hugo’s release, Ghacha describes her encounter with Supervising ICE Officer Buchholz at Adelanto Detention Center: Ghacha states that Buchholz found Interpol’s temporary block insufficient for the release of Hugo. She adds that Buchholz said he would reconsider his decision if Interpol were to delete the data against her client after their investigation. In addition, Ghacha writes, Buchholz said he personally called the Guatemalan Embassy to confirm the charges against Hugo in Guatemala were still pending and found this to be another reason for the denial of the release request. (Buchholz did not respond to a request for an interview with palabra.)

Sandra Grossman, an immigration attorney and member of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, specializes in Interpol matters. Grossman is not familiar with Hugo’s case, but noted that in order for CCF to have initiated a data block, there must be some evidence from the country seeking an individual’s arrest that may not be in compliance with Interpol’s rules.

“They (CCF) want to make sure that they don't run afoul of their mandates by continuing to process negative information about a person that may be in violation of human rights,” Grossman says.

Grossman adds that a long time gap between the issuance of an Interpol Red Notice on an individual to the time of their arrest is not uncommon. She says arrests often depend on law enforcement priorities, changes in the cases or if a case’s priority was elevated for some reason.

“In the case of when he is deported, he and his team will have three months to prove his innocence (in Guatemala), which is a guaranteed right for him,” explained Hilda Pineda to palabra in June of 2021 in her then role as the prosecutor of the Human Rights Prosecutor’s office in Guatemala City. (In October of 2021, Pineda was transferred to a new office pursuing crimes against tourists by Attorney General Consuelo Porras.)

If Hugo Gomez is ultimately convicted of being involved in the disappearance of Edgar Fernando García, it would prove that even where people think justice is not possible, long-ago crimes can yet be punished.

Leonor sings with joy as Sunday service is held at a park to celebrate the 4th of July. Leonor has found some momentary reassurance with the current block on Hugo’s case. July 3, 2022. Photo by Zaydee Sanchez for palabra

That possible outcome is not lost on Leonor. It fuels her determination.

In her home, she scrolls through her phone, watching old church videos of Hugo, when he preached to hundreds of married couples. The sound of Hugo’s voice from the phone fills the quiet kitchen. Footsteps upstairs are a reminder of Debbie’s presence. Leonor's eyes begin to twinkle as the video continues playing. She smiles, lets out a small giggle then begins to weep. “If she (Nineth) would come out and say, ‘I was wrong,’ then I would feel served,” Leonor says, underscoring her belief that Nineth somehow holds a key to Hugo’s fate. “I can’t stay quiet. I have to show her my truth. I’m not going to rest.”

As for Nineth, Fernando’s legal case concluded nine years ago. She reiterates that she, personally, has never sought anything against Hugo. “If they deport him (Hugo) I have nothing to do with this. I do not know how the judges will react here (in Guatemala) but we have not asked for anything against him,” she says.

—

Abraham Márquez is a freelance writer from Inglewood, California, focusing on immigration, and politics.

Zaydee Sanchez is a Mexican - American visual storyteller, documentary photographer, and writer. Her work is rooted in addressing the complexities of migration. With a focus on labor workers, gender, and displacement, she seeks to highlight underreported communities and overlooked narratives. Zaydee is an International Women's Media Foundation grantee and a 2021 USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism Fellow. Her work has been published in Al Jazeera, National Geographic, NPR, and other outlets. She resides in Los Angeles.