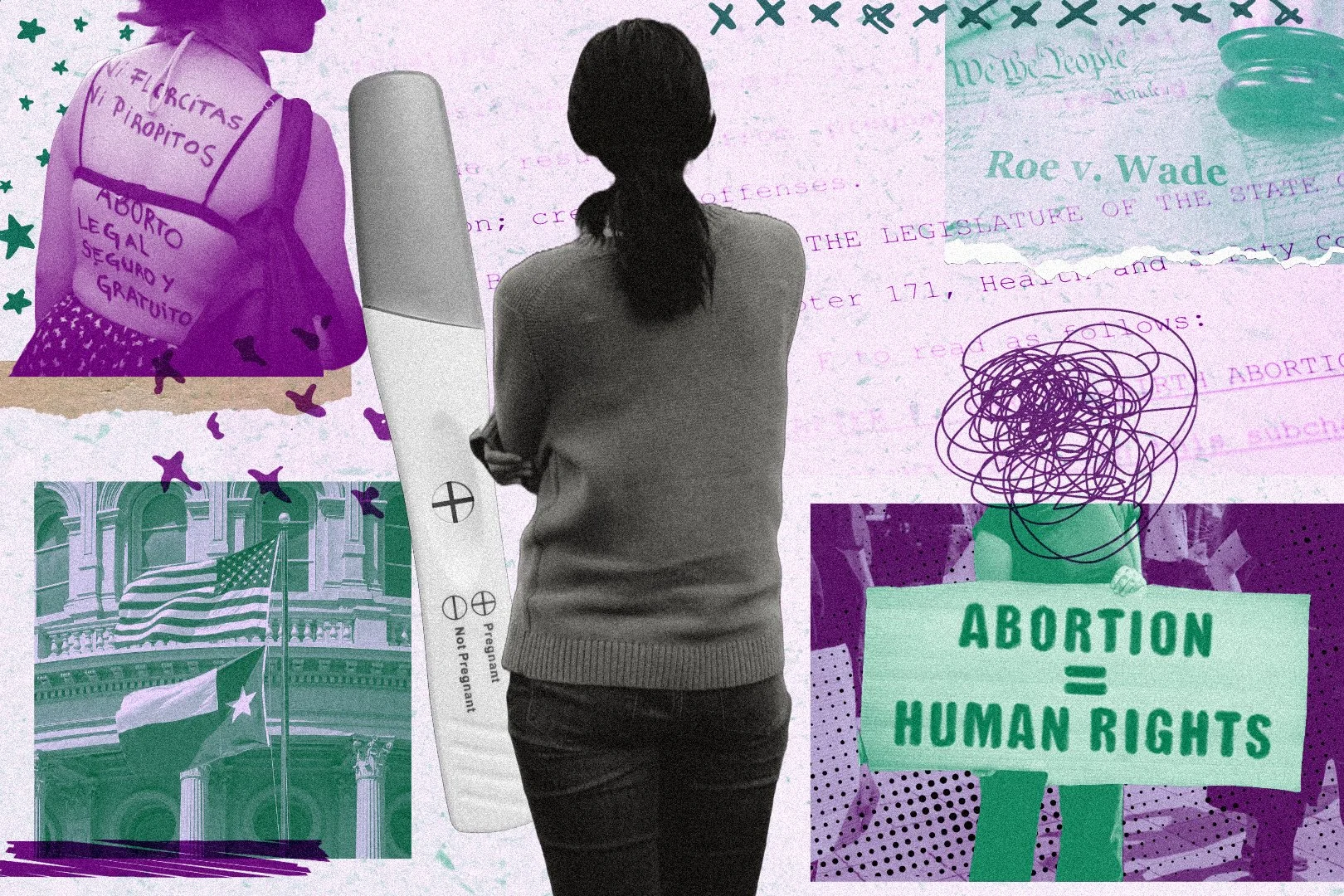

Abortion without Papers: A Hidden Struggle

Photo by Valerie Sigamani via Unsplash. Photo collage by Yunuen Bonaparte for palabra

For immigrants without documents, the fight for reproductive rights is a high-stakes battle against fear, borders, and a system stacked against them.

Editor’s note: This story was originally published by Reckon. Subscribe to Reckon’s newsletter.

The ongoing impact of abortion bans and fetal personhood laws continues to shape who can access reproductive care and how, with marginalized communities facing the most significant obstacles. Immigrants without documents face numerous barriers, including lack of insurance, language barriers, and the constant threat of criminalization or deportation, particularly in states with strict immigration policies. Abortion advocates say these risks create a difficult choice for some people without immigration status: remain pregnant or potentially face separation from their families.

About half of immigrants without documents are uninsured, according to a Sept. 2023 KFF report.

“Travel is really one of the biggest barriers to access abortion for everybody, but we know that that just proportionately impacts people who are undocumented as well,” said Meghan Daniel, director of services at Chicago Abortion Fund (CAF). “Additionally, undocumented people have a harder time accessing IDs, documents, etc. (and) somebody asking about their health in their preferred language is really important to bodily autonomy.”

Zaena Zamora, executive director of Frontera Fund, an abortion fund serving people within 100 miles of the Texas-Mexico border, notes that Texans have been navigating a post-Roe reality, even before the ruling, due to restrictive abortion policies. This has led to Texas having the most abortion deserts in the country, according to the Center for Reproductive Justice.

“We are the farthest away geographically from every other ‘safe space,’ in safe states in the United States,” said Zamora. “So if our callers are coming from McAllen, TX or Brownsville, that's upwards of like a 12-hour drive just to leave the state, right? So there's a lot of barriers that people have to navigate. Travel is very expensive and costs a lot of time and money.”

In a 2022 Teen Vogue op-ed Brenda Rodriguez Lopez, executive director of Washington Immigrant Solidarity Network, described the dilemma she faced navigating the compounding barriers of abortion as a person without immigration status.

“Many of us do not have the luxury of paid time off for an abortion, or any medical procedure. When I got an abortion, like most undocumented folks I didn’t have healthcare coverage. I didn’t know abortion funds existed, and I was running against the clock,” she wrote. “For many undocumented people, crossing state lines is not an option because of Border Patrol checkpoints (which operate in areas within 100 miles of a U.S. border).”

A July Pew Research Center report estimated 11 million immigrants without documents lived in the U.S in 2022, with about 1.6 million residing in Texas, the second highest undocumented population after California.

Zamora says most of Frontera Fund’s clients are Latino/x, many with low incomes, uninsured or underinsured, and an estimated 60% are already parents. It’s difficult to track how many individuals without documents have abortions, as most abortion funds and clinics don’t collect this data. However, the nuances of communities without immigration status face in navigating immigration and abortion laws, in a state as restrictive as Texas, can significantly impact their access to care.

‘They're afraid of being asked about their immigration status, but this is an executive order.’

According to the New York Times, 171,000 people traveled for abortion last year, including 14,000 patients from Texas fleeing to New Mexico and 16,000 Southerners to Illinois. Abortion funds like CAF, help patients mitigate funds, with the average support cost they provide $380, and the average voucher they provide for procedures is $480, CAF’s executive director Megan Jeyifo told Salon in April.

The average cost of traveling for an abortion, including transportation, lodging, the procedure itself, and childcare given that many people who seek abortion are already parents, can range from hundreds to thousands of dollars, creating a significant financial barrier for individuals funding their care out of pocket.

While travel costs are a barrier for many in states with abortion bans, navigating specifically out of Texas is particularly complex due to the heavy border patrol presence. There are 45 border patrol stations in Texas listed in the U.S. Customs and Border Control website, more than any other state.

Zamora described the Falfurrias checkpoint, north of her hometown McAllen, as a large compound reminiscent of the Texas-Mexico border, with law enforcement, Border Patrol, K-9s and cars lining up awaiting inspection. Some dread the question: “Are you a U.S. citizen?”

“If they suspect, or if the dog suspects something in your car they'll have you pull off to the side. They can search your vehicle. They can detain you. They can ask you questions, it just depends on the border patrol agent that stops you,” she told Reckon. “Sometimes they'll just look at you and they'll wave you along and not ask you anything and sometimes they'll ask you ‘where are you going? Why are you going there?’”

Security checkpoints are part of Texas’ multi-billion dollar effort to restrict illegal immigration. In 2021, Gov. Gregg Abbott launched Operation Lone Star, investing $11 billion in border security. Last week, Abbott signed an executive order requiring Texas hospitals to disclose healthcare costs spent treating immigrant patients without documents, though the El Paso Times reports no clear guidelines on how to obtain patients’ citizenship status were given.

Zamora said this policy adds to the fear of interacting with healthcare facilities.

“Right now people are going to be afraid because they're going to be asked their immigration status, which was already a fear to begin with. A lot of people don't like to go to doctors or to official places like that, because they're afraid of being asked about their immigration status, but this is an executive order, now they're going to be asked about it.”

The fear is not unfounded, as medical deportations have been reported in the U.S. A 2012 study found that more than 800 immigrant patients were involuntarily deported from hospitals in 15 states, likely an undercount as hospitals aren’t required to report medical deportations, according to Newsweek. Philadelphia became the first U.S. city to ban medical deportation without informed consent in December 2023.

Further complications for Latinas

An October 2023 report by the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice (Latina Institute) and National Partnership for Women and Families (National Partnership) found Latinas were the largest group of women of color living under abortion bans, nearly 6.7 million.

“Particularly for the Latina community and immigrant communities at large, we know that our communities bear the brunt of extreme policies that have robbed us of the tools and the resources that we need to stay healthy and to make informed decisions about whether and how we want to become parents, and to raise our families with dignity and safety,” said Katherine Olivera, director of government relations at the Latina Institute.

Maternal mortality is also higher for all racial and ethnic groups living in states with abortion restrictions, with Latina maternal deaths in these states 31% higher, according to a 2022 maternal health report by the Commonwealth Fund.

Abortion bans further complicate a healthcare system many undocumented individuals avoid for fear of repercussions, preventing some from seeking even basic care, according to Olivera.

“When you couple your reality as it relates to either facing criminalization due to abortion being criminalized or criminalization simply because you don't have the proper legal status or documentation, immigrant communities fear obtaining the care that they need from going to providers that may often report them to authorities.”

‘So it's a double edged sword, right? You're sacrificing your health or jeopardizing essentially your existence in the state.’

Olivera told Reckon that while many self-manage abortion at home to avoid the risks, that isn’t an option for everyone.

“The reality at large is that many people can't travel to get the abortion care that they need and then may be forced to remain pregnant which is a form of torture as defined by human rights experts,” she said.

Olivera referred to these options as a double-edged sword.

“There's that real risk of deportation, being separated from your family and detained, so it's a double edged sword, right? You're sacrificing your health or jeopardizing essentially your existence in the state or the place that you find yourself due to these laws criminalizing immigrants,” she said.

Even citizens face healthcare obstacles in the form of language barriers. The National Partnership report states over 1 million Latinas in states with abortion bans don’t speak English well or at all, with over 99% being Spanish speakers.

Support the voices of independent journalists.Donate to palabra today! |

“Even for those who are insured, access to culturally competent and culturally responsive health care is another gap for our communities,” said Olivera. “Or services that are not consensual simply because you did not understand the services that you are agreeing to due to the language barriers and the sort of systemic issues that continue to be at play.”

Daniel told Reckon that in preparation for Florida’s six-week abortion ban that went into effect in May, CAF prioritized hiring more Spanish speaking support coordinators to meet the needs of patients, and contract with interpretation services to support callers who speak languages outside of English and Spanish. While Daniel says these steps are important, the need for equitable healthcare policy goes beyond what abortion clinics can provide.

“There's just such a critical role for policy change in addressing the sustainable demands on states where abortion remains legal and then also trying to chip away at the bans in states where it has been banned so that people can get care closer to home,” said Daniel.

Policies like the Affordable Care Act (ACA) have extended coverage to millions of Americans, but undocumented communities remain ineligible for these federally funded programs.

“As a result we're seeing greater communities being uninsured or underinsured, and not having access to regular and consistent providers,” said Olivera.

One avenue advocates are exploring for more equitable healthcare for immigrants is the HEAL Act, which would remove the five-year ban preventing green card holders from accessing Medicaid and CHIP, and open the ACA marketplace to immigrants without documents.

“If reproductive justice is the belief that everyone should be able to determine if, when, and how to start a family and to raise that family in a safe and sustainable environment, that vision is impossible to achieve if it is not inclusive of immigrant communities,” says Lucie Arvallo, senior policy analyst at the Latina Institute told Reckon in September.

Annabel Rocha is a multimedia journalist for Illinois Latino News (ILLN). A native Chicagoan, Annabel graduated with a BA in Journalism & Media Studies from the University of Nevada-Las Vegas in 2018. Her areas of experience include broadcast production, news writing and interviewing. She now resides on the south side of the city, with hopes of amplifying local Hispanic/Latino voices and sharing stories of inclusion and diversity. @AnnabelRocha93