But Who Can Hear You in the Desert?

A photograph shows Laura Coc (far right), a young woman from Guatemala, posing during a beauty pageant. Photo by Andrea Godínez

In one Arizona morgue alone in the U.S. there are more than 300 unidentified remains of migrants. Their bones and belongings sit in cardboard boxes in a nondescript trailer in a parking lot

Editor’s note: This story is part of the series “Migrating and Vanishing.”

Laura and her brother started their migration 13 years ago. They set off for the U.S. to work and send money to their family, as many people from Guatemala do. But they didn’t make it. Laura is one of at least 817 Guatemalan migrants that disappeared between 2010 and March 2023. Even Guatemala’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs acknowledges that this number — which comes from the missing persons cases filed with their office — is an undercount. The same problem with record-keeping occurs in Mexico, where the only certainty is that they do not know how many migrants have gone missing in their territory. According to the International Organization for Migration, the route to the U.S. from Central America is the third most dangerous in the world.

Haz clic aquí para leer en español.

January 15, 2009

Laura Coc is 18 years old and competing to be the village beauty queen in Xesuj, San Martín Jilotepeque, Guatemala. Her long black hair is styled simply: parted in the middle and gathered in a low ponytail. Like every other contestant, she wears a traditional huipil, with a flowered sash and a long colorful skirt. She poses for the picture that will immortalize her participation in the 2008-09 pageant. With a shy smile, she looks at the camera and waits.

October 4, 2010

The sun rises over the Arizona desert in the U.S. The morning light colors the sky in shades of orange over the still landscape. The shapes of cacti resemble soldiers on duty. Laura Coc's lifeless body lies beneath a thorn-strewn bush. Her brother left her there when he realized that if he didn't seek help, he would die too.

March 27, 2023

A coroner in Pima County, Arizona, pulls out a box from a stack that rises all the way up to the roof of a truck trailer. Taped on the side of the box, under the hole that serves as a handle, is a piece of paper with a case number. The coroner lifts the lid and pulls out a skull, a piece of unidentified human remains.

Gene Hernández, a forensic medical investigator in Pima County, holds the skull of a deceased migrant. Photo by Andrea Godínez

Every day for the last 13 years, whenever Roman Coc hears the dogs barking in his house in the mountains of Guatemala, he thinks that his daughter Laura is approaching. He wonders if she will find the house because the entrance was repaired some time ago.

Laura's body, Laura's bones, Laura's clothes. None of it was found.

How many more like Laura?

Between 2010 and March 2023, Guatemala’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs received reports of 817 Guatemalan citizens missing in foreign countries. More than half of them were between the ages of 18 and 30 when they left from homes in the departments of Guatemala, Quetzaltenango, Huehuetenango and San Marcos. Those last two departments are located along the Mexican border.

Of the missing, 52 are women. This data is neither on a public record nor is it accessible to the families: It was obtained via requests for access to public information made to the Guatemalan Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Guatemala for this investigation.

When Román Coc filed a report for his missing daughter at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he was told to remain calm, that there would be a search for her. Andrés was the name of the man who spoke to Román and gave him a phone number. But when Román called that number, he was told that there was a “change of personnel” and that Andrés was no longer there to answer. “My case, I don't know if they followed it up,” says Román. “Because they promised to call me back. In 13 years we received four calls, at the beginning, and then no more.”

At the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the number of missing Guatemalan migrants is underreported, a fact acknowledged by the vice-consul Geovani René Castillo Polanco, in an interview conducted for this investigation:

— Does this seem like an accurate number to you, or could there be more?

— There may be more. It is unfortunate to say, but many bodies are found piled up in the desert. Sometimes their fellow migrants bury them. Sometimes coyotes (human traffickers) make them disappear. But that figure is not accurate. The numbers are higher.

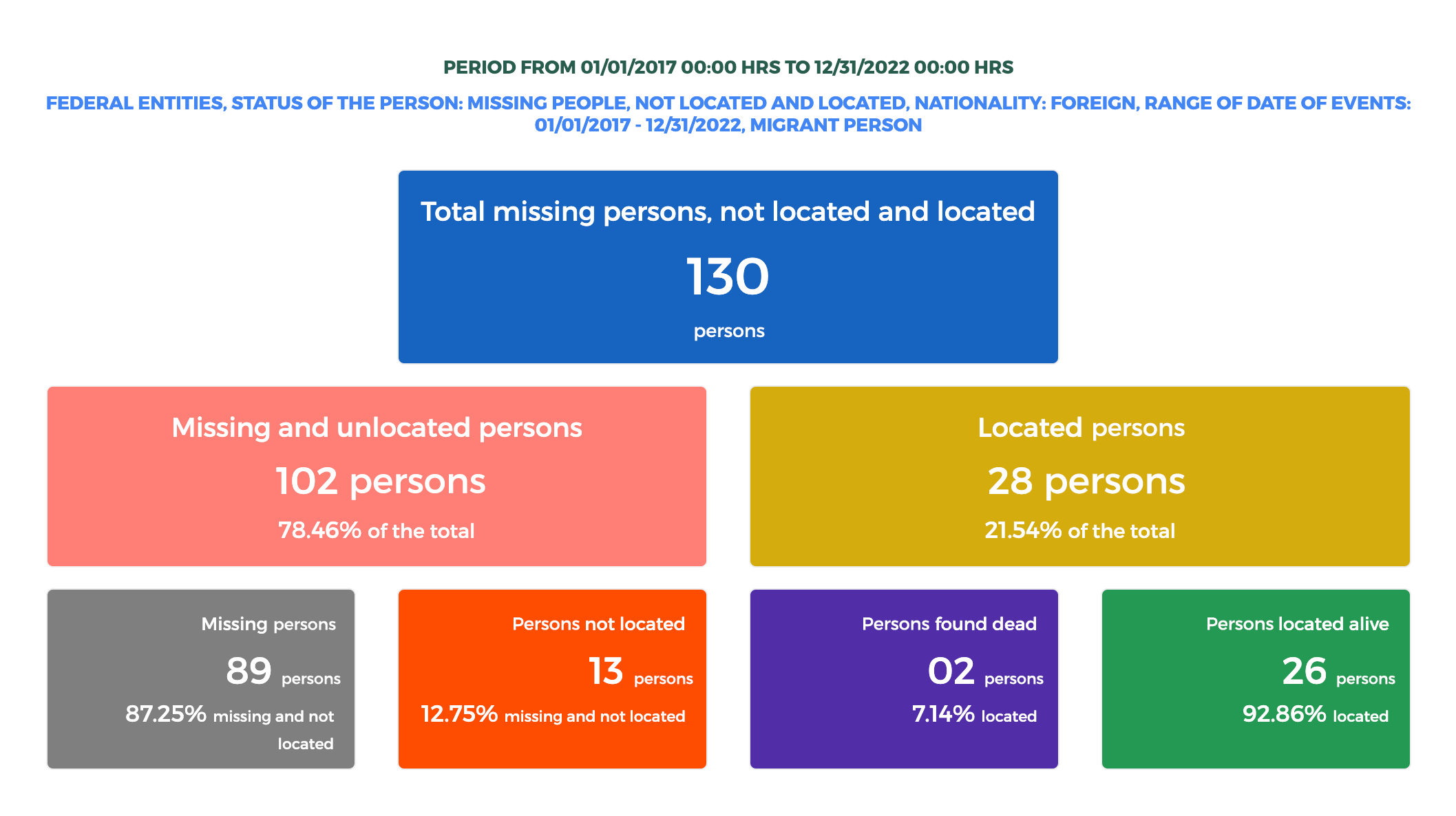

However, underreporting is not only a problem in Guatemala. In Mexico, the number of migrants reported missing between 2017 and 2022 varies depending on who you ask. There may be 1,270 according to state prosecutors, or 124, as reported in the public database of the National Search Commission (Comisión Nacional de Búsqueda, CNB).

Statistics from the National Registry of Missing and Unlocated Persons (RNPDNO). Source: National Search Commission. The prosecutors’ offices send the information to a national database that references the year the person went missing, not the date that the report was filed. This is why the number of missing persons in a particular timeframe is updated.

After six months of requests for interviews to inquire about the discrepancy in these numbers, Sonja Perkic-Krempl, general director of search actions for CNB, replied, “The figure that we use as we oversee the search for migrants is about 1,300 missing persons, counting the cases that we are aware of, and that we follow up on and then a search gets underway.”

The official acknowledged that they are aware of many more cases than the ones documented in their public database. However, when asked for this data, the official refused to share it, alleging that the database was in a "standardization phase".

The only certainty is that Mexico does not know how many migrants have gone missing in its territory, nor how many of them have been found dead. And Guatemala acknowledges that it has no data on how many of its citizens have disappeared while attempting to migrate to other countries.

Castillo Polanco explained that most of the Guatemalan migrants reported missing have disappeared along the border between Mexico and the U.S.: "That stretch of the desert is one of the most dangerous worldwide. It is called the pass of death, and it’s where most loss of human life occurs,” he says. Data from the International Organization for Migration corroborates this: the route to the U.S. is ranked as the third most dangerous in the world.

In three years (2019-21) the number of dead migrants at the border tripled from 255 to 900, according to data provided by Customs and Border Protection (CBP), in response to a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. That is the impact of U.S. immigration policies: militarizing the entire border and leaving open the most dangerous and inhospitable areas does not have a deterrent effect and have instead resulted in an increase in the number of migrant deaths, according to immigration experts.

According to data provided by Mexico’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, of the 7,773 reported migrant deaths along the U.S.-Mexico border over the last 22 years, 3,053 occurred along the Tucson border that runs through the Arizona desert. In other words, almost half of the migrants who died at the U.S. border perished in the same desert as Laura Coc.

In the mountains of Guatemala

The path to Román Coc's house follows a mountain road surrounded by a landscape of pine trees and volcanoes. Sudden curves and switchbacks change the point of view swiftly. It is a two-hour drive from Guatemala City, but the vehicle can only get as far as an isolated supply store. The rest of the journey has to be completed on foot along a steep path. During those last 500 meters the only sounds are the footsteps on the fallen leaves, the singing of birds and the sounds coming from distant mountains.

Román Coc holds photos of his daughter Laura, who disappeared in the Arizona desert 13 years ago. Photo by Andrea Godínez

Román is 69 years old. He has 10 children, 21 grandchildren and an amiable face. He has lived in the village for 40 years, having moved there shortly after getting married to escape the violence in the region where he grew up. He built the house himself. It was humble at first, but he kept working on it and expanding it over the years — to the point that several of his children and grandchildren currently live there.

He worked as a farmer his whole life. He planted corn, beans, coffee, oranges, peaches and bananas. But it became more difficult for his children. In Xesuj there is no work, and the little work that becomes available is poorly paid. “The kids want nice things, or to do the things they want,” says Román.

That was one of the reasons why his daughter Laura decided to travel to the U.S. at the age of 21.

— What are you going to do? — he asked her.

— I'm going to support you, to help you get ahead.

“But it didn’t turn out like that,” he says now, seated on a wooden chair in the patio that separates the eat-in kitchen from the bedrooms. In one of those rooms, the floor is littered with pine needles. In one corner, there is a bed. In the other, an altar with Laura's photo from the beauty pageant. Outside the room, a calendar leaned against the wall reads: shipments from Guatemala to the United States. Román's patio is full of color: yellow-painted walls, red curtains, flowerpots, and a clothesline with clothes hung to dry in the sun. The clothes are similar to the outfit Laura was wearing the day she left.

Román Coc in the patio of his home in a mountain town in Guatemala. Photo by Andrea Godínez

Laura in the desert

Román knows only a part of what happened that day in the desert.

"She began to faint. Two of them carried her along, and once she collapsed she could no longer walk. And the guide said 'leave that there, leave your sister, or we will all fall'". At this point in the story, the father's voice starts to fade. "But he didn't leave his sister. At about midnight his sister died in his arms."

Laura’s brother tried to call for help. “But who can hear you in the desert?” asks Román.

The boy placed Laura’s body under a bush, tore a T-shirt he carried in his backpack, leaving a trail of fabric on the road so he could find his way back. Then he walked in the direction of the Mexican border. He remembers coming across a highway. Cars crossed the desert like a tidal wave. No one listened to him. When he managed to find an immigration post, he begged them to go look for his sister, but they did not listen.

The father's recollection of his son’s timeline becomes hazy, but he recalls that, at some point, the boy was able to return to the spot where he had left his sister, only to find her missing. All that remained was one of her tennis shoes.

Then, he was deported.

“The desert took his sister, and he felt he had to go back to the desert,” says Román of his son, who has made several more attempts to enter the U.S. but has never made it across.

Thirty-eight hundred kilometers away from Román's patio, across Guatemala, Mexico and the Arizona desert, there is another concrete patio. It is a parking lot. There is the silver trailer that is so impeccable — on the outside — that it refracts the sun's rays, blinding people who walk by. It is the courtyard of the Pima County Sheriff's Office, where boxes filled with the remains of migrants who have not yet been identified are kept.

A truck in the parking lot of the Pima County Morgue holds boxes filled with the remains of deceased migrants. Photo by Andrea Godínez

Seated at his desk, Gene logs into his computer, opens a map, clicks the search button, and finds the state of Arizona flooded with numerous red dots layered atop one another, resembling a paint spill. Each dot marks a spot where human remains have been found.

The interactive map was developed jointly by the Pima Coroner's office and the nonprofit organization Humane Borders, Inc. It is fed by a database that shows all the cases of deceased migrants received by Gene's office. As of June 2023, there were 4,005 cases. The oldest is from November 25, 1981, and remains unidentified.

Gene Hernández displays a map covered in red dots that mark the spots where the remains of deceased migrants have been found along the U.S.-Mexico border. Photo by Andrea Godínez

— How is it possible to identify someone who was found so long ago?

— We need the help of the families. The families have to talk to us and tell us that they are looking for their relatives, so they can send us a DNA sample for us to compare with the ones we have here.

The neatly labeled brown boxes are kept in a trailer at the morgue due to lack of space. In 2024, the morgue will open a new office and the boxes will be moved. “All these people are waiting to be identified,” Gene explains.

Migrants who, lost to their families and dead in a box, are still waiting.

Each box contains bones and the belongings of one or more migrants who perished while attempting to cross the border. Photo by Andrea Godínez

This investigation was produced with the support of the Consortium to Support Independent Journalism in Latin America (CAPIR) led by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR).

—

Verónica Liso is an Argentinean product manager for digital native media and a freelance investigative journalist since 2013. She specializes in judicial journalism and data journalism. She has been published in Cosecha Roja, Infojus Noticias, Página 12, Revista Anfibia, eldiario.ar, Perycia, among other outlets.

Rosario Marina is a journalist specializing in data and narrative. She studied at the National University of La Plata, in Argentina. She has been covering human rights, gender and LGBTIQ issues, migration and police violence for 10 years for media outlets in Spain, Guatemala, the U.S. and Argentina.

Gabriela Olga Villegas is a regional digital content editor for Univision Texas and Chicago. She is the winner of a Lone Star EMMY for winter weather coverage in North Texas with the Noticias 23 team. She worked for more than seven years as a journalist for El Norte and Reforma in Monterrey, Mexico, where she began in daily news coverage and also conducted investigative journalism focused on corruption that had a national impact, such as the detour of resources in social programs and the favoritism of politicians with companies to distribute contracts and bids.

Andrea Godínez is a Guatemalan social communicator with a seven-year career devoted to photojournalism and the production of journalistic content, focusing on issues such as migration, poverty and social inequality. She studied communication sciences at Rafael Landívar University.