Dreaming of Empires

Álvaro Enrigue, author of “You Dreamed of Empires,” in the Hamilton Heights neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. Photo by Yunuen Bonaparte for palabra

Álvaro Enrigue’s latest novel is a trippy, thought-provoking reimagining of a seminal point in the history of the Americas: When Cortés came calling on Tenochtitlán.

Words by Rich Tenorio, @rbtenorio. Photos by Yunuen Bonaparte, @_ybonaparte. Edited by Ricardo Sandoval-Palos, @ricsand.

In 1519, a fateful collision of civilizations took place in Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Mexica Empire. Moctezuma Xocoyotzin, the huey tlatoani — the emperor — of what the Spanish would mangle and rename the Aztec world, warily greeted an army of strangers from the East: the forces of Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés. Two years later, the once-beautiful, architecturally stunning metropolis was destroyed, the powerful empire conquered, and its subjects the victims of war — or of infectious disease unwittingly introduced by the Spaniards.

But what if a different narrative had unfolded? What if the emperor knew exactly what he was doing when he inexplicably allowed the Spaniards to march all the way from what is now known as the Gulf of Mexico to Tenochtitlán? That’s the premise of “You Dreamed of Empires,” a daring new novel by celebrated Mexican writer Álvaro Enrigue.

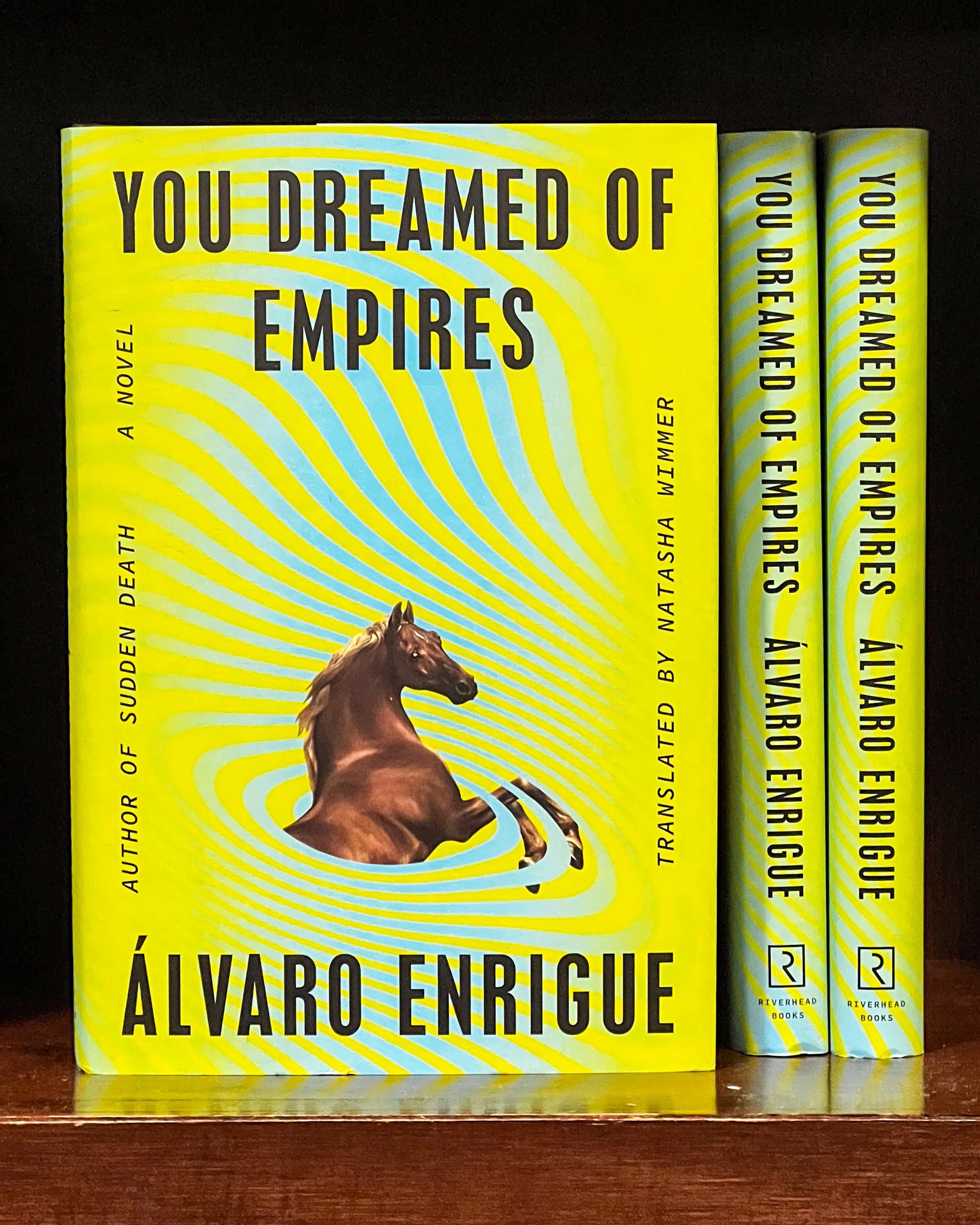

"You Dreamed of Empires" at the Barnes & Noble bookstore in Union Square, Manhattan, New York City. Photo by Yunuen Bonaparte for palabra

The novel reintroduces readers to the well-known historical figures of Moctezuma, Cortés and Malintzin, a Nahua princess who became Cortés’ translator and lover, and is referred to in the book as Malinalli. (Moctezuma’s full title was huey tlatoani, which the author explains means “great lord of Tenochtitlán.” In the creative language of his book, the Mexica view Cortés as “huey Caxtilteca,” or “a Castilian lord.”)

Enrigue also created two imaginary characters: Mexica princess Atotoxtli, who attempts to counsel her brother-husband, Moctezuma, on affairs of the state; and Spaniard Jazmin Caldera, one of Cortés’ commanders, who is fascinated by the Mexica despite an all-too-visceral encounter with their practice of human sacrifice. Along the way, Enrigue meditates on the themes of capitalism and colonialism that have flowed from the Spaniard-Mexica encounter 500 years ago.

When palabra asked about his decision to create alternate universes, Enrigue had an answer ready.

“It’s just to change the point of view and give the center stage to the people of the Americas — not as the ‘other’ but as regular, political human beings,” he says. “I try to do that literary exercise — change your point of view, unlearn everything we learned about the situation with the Americas, before the arrival of the Europeans … imagine what a wonderful world this would be if there had not been a colonial system for 300 years in the Americas.”

‘It has to do with the freedom of the fiction writer…You can say things that a historian, a philosopher, a sociologist simply cannot say.’

Enrigue’s interest in the fall of Tenochtitlán and its impact has deep roots dating back to the excavation of Mexico City that began in 1978 and yielded a majestic Mexica complex known as the Templo Mayor, which once dominated Tenochtitlán as a center of worship. The future author was a kid back then. He remembers visiting the site on a school trip, and the encounter made him think of ancient Rome. He saw Mexico City reconnect to its pre-colonial past, transforming what he perceived as a stuffy, provincial place into a beautiful megalopolis. Although he eventually relocated to New York City as an adult, Enrigue never lost his connections to his homeland and its history. He also contemplated an alternate early history for Mexico, having grown disenchanted by present-day political trends, namely the effects of globalization and right-wing populism in the U.S., Europe and Latin America.

Álvaro Enrigue answers emails at home in Manhattan. His walls are lined with books and artifacts representing his Mexican culture. Photo by Yunuen Bonaparte for palabra

Although he intended this novel to explore these broad themes, he also wanted to document the details of everyday life in Tenochtitlán. He exhaustively researched sensory details: What did the place smell like? How did its inhabitants dress? How did indigenous people pronounce their names and those of the Spaniards? Enrigue explains his decisions with regard to spelling and pronunciation in an explanatory note to Natasha Wimmer, who translated the novel from Spanish to English. Enrigue’s note accompanies the text.

He had to describe what it felt like for two peoples to viscerally absorb each other and their cultures for the first time. One such encounter, between the Mexica and the Spaniards’ horses, allowed him to play with history. “It has to do with the freedom of the fiction writer,” Enrigue says of this plot twist. “You can say things that a historian, a philosopher, a sociologist simply cannot say. There is no scientific method for writing fiction. The great question we have asked over 500 years in Mexico is: why did Moctezuma let the Spaniards go into Mexico City? Why didn't he just wipe them out when they disembarked and that was it? Why did he let them (form) all these alliances (with indigenous peoples) that produced a bigger army?”

In the novel, Moctezuma is intrigued by the horses, to the point of allowing the Spaniards unhindered access to his capital so that he can surreptitiously capture their mounts. “It is true,” Enrigue adds, “that (indigenous) American nations that adopted horses resisted Europeans until the 19th and 20th centuries … It was not all the other technologies, but really the horse that changed the course of history, their appearance in the Americas, mounted by Europeans and all the people of North America who were able to resist … The novel plays with that.

“It’s just a play. I think that’s important to say. It is fiction, but a game. Fiction is only a game. You can see it as a political discourse on how history is told. Maybe it’s a psychedelic comment discussing an important truth. For me, it’s a game.”

Álvaro Enrigue at home in Manhattan. Photo by Yunuen Bonaparte for palabra

It seemed like the right moment for palabra to bring up another plot device, namely the Mexica’s affinity for magic mushrooms.

“I can engineer. I’m a builder, an engineer of the time of the novel,” Enrigue says. “It moves things to the consumption of hallucinogens by Moctezuma on page five or ten. From then on, he’s consuming more and more hallucinogens, getting higher and higher. The story begins to change. I use that as a way of moving the time of the novel.”

As the novel heads toward its climax, it’s Cortés who goes on a hallucinogenic trip — through cacti rather than mushrooms. In it, Moctezuma reveals himself as a nagual who can transform into a protective animal figure and who can also speak Greek. It turns out to be a very revealing “magical mystery tour,” as the Beatles might say.

The novel also describes scenes of unimaginable violence. Moctezuma and his lieutenant, Tlilpotonqui, sentence subjects to death, while a high priest wears the flesh of a human sacrifice. Cortés presides over a mass slaughter of the indigenous community of Cholula (a real historical event), and rapes Malintzin out of anger.

Mexican author Álvaro Enrigue in Upper Manhattan. He has lived in New York City for two decades, since the Mexican economic crisis of 1994. Photo by Yunuen Bonaparte for palabra

“It was a very gory world on both sides,” Enrigue says. “More than the U.S., Europeans still have the idea of the occupation of the Americas as hygiene: The worst people disappeared in the name of a Christian people. Of course, it’s an incredibly limited and stupid idea … The novel, in the first place, tries to show the humanity of the people of the Americas. It was a tough world on both sides. The novel is about the brutality of history. It was not a gentle process. It’s also worth noting that we live in a horrific world. The way we got here was through abuse and cultural destruction.”

—

Subscribe to palabra’s newsletter.

Rich Tenorio is a writer and editor whose work has appeared in a variety of media outlets. He is a graduate of Harvard College and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.Tenorio is also a cartoonist. @rbtenorio

Yunuen Bonaparte is a photojournalist and visual editor based in New York. She is currently the photo editor at palabra and Narratively. @_ybonaparte

Ricardo Sandoval-Palos is palabra’s founding editor. He is the public editor for PBS, an intermediary on ethics, integrity and standards between the broadcaster’s audiences and its creatives and journalists. Ricardo is an award-winning investigative reporter and editor. His reporting in Latin America earned awards from the Overseas Press Club and the InterAmerican Press Association. He’s also co-author of the biography “The Fight In The Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers Movement.” @ricsand