Voting in English y en español

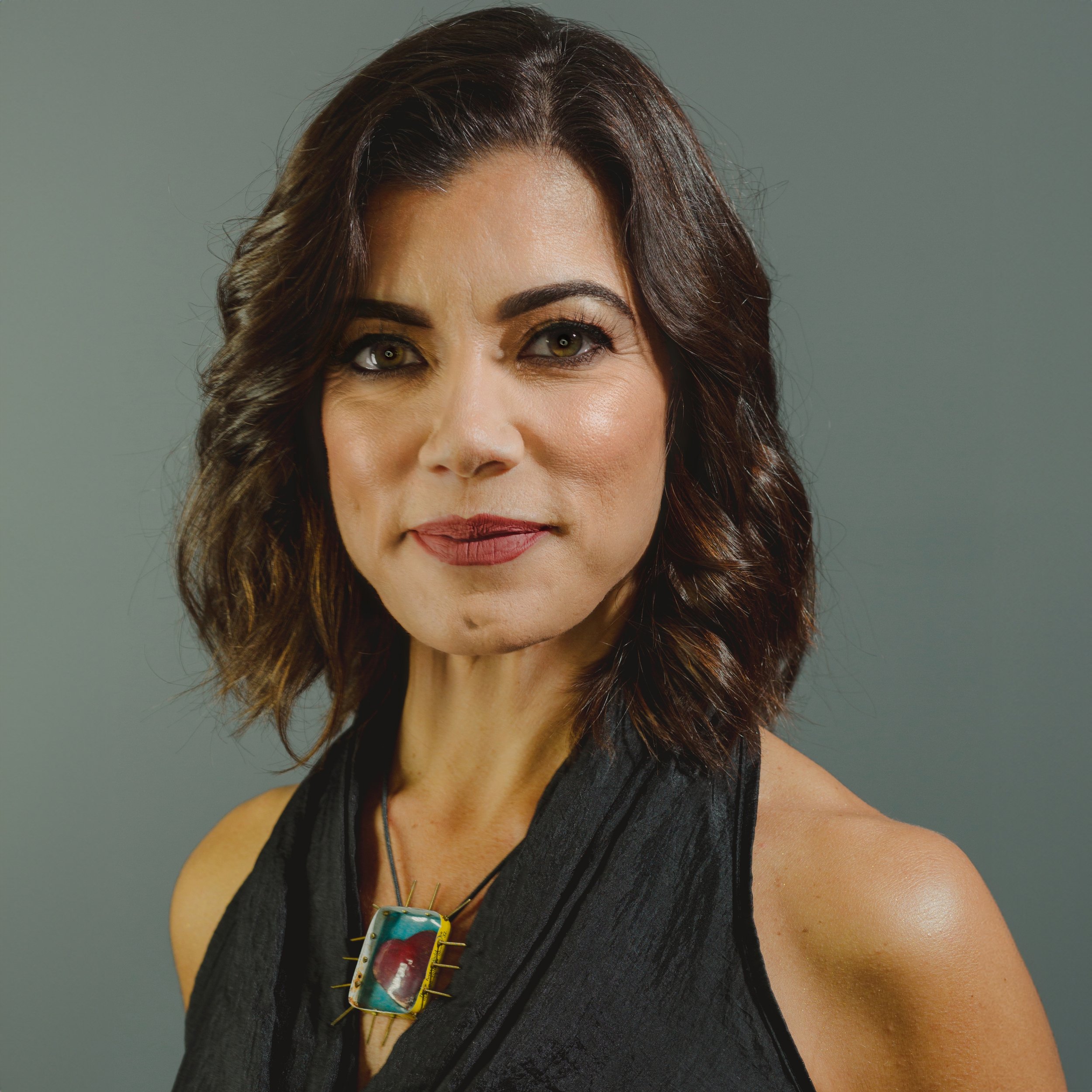

Ana Villamil votes at the Best Friend Park polling location in Norcross, Ga., during the presidential primary on Tuesday, March 12, 2024. Photo by Bita Honarvar for palabra

After the number of voters who speak Spanish as their primary language surpassed 10,000 in Gwinnett County, Georgia, a federal requirement kicked in, forcing officials to translate ballots and other election materials

Carlos Zavala, 48, commutes on a busy four-lane highway to the Gwinnett County Board of Voter Registrations and Elections in Georgia, housed in a former Walmart in a strip mall in Lawrenceville, the county seat.

Zavala is an elections associate. Part of his job is to translate voting materials to thousands of eligible voters in Gwinnett County who speak Spanish as their primary language, a mandate under a provision of the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 known as Section 203.

Section 203 requires the translation of ballots and other election materials when speakers of Spanish, Asian, Native American and Alaskan Native languages — “language minorities that have suffered a history of exclusion from the political process” — surpass 10,000 or more than 5% of the voting-age population.

The mandate has become a requirement in states like California, Texas and Florida, with large and generations-old Latino populations, and in parts of North Carolina and Arkansas, which have recently reached the required threshold.

Carlos Zavala, elections associate at the Gwinnett Voter Registrations and Elections in Lawrenceville, Ga., greets a passerby as he mans a table outside the elections building to recruit poll workers, help people with voter registration and absentee ballots, and promote the county’s language assistance program. Photo by Bita Honarvar for palabra

In Gwinnett County, the requirement was implemented in 2016, when the number of Spanish-dominant voting-age citizens crossed the 10,000 mark. To date, it’s still the only county in Georgia required to translate all voting materials to Spanish.

With around a million residents, Gwinnett is the second most populous county in one of the nation’s fastest growing states. Its population has nearly tripled since 1990 — and the explosive growth has brought profound changes. Gwinnett was once a largely white area, with an all-Republican county commission. These days, white people are the minority, one in five residents is Latino and the Gwinnett County Board of Commissioners has just one Republican member.

Jerry González, executive director of the nonpartisan Georgia Association of Latino Elected Officials, said his group faced resistance when it tried to convince county election officials to prepare for the federal translation requirements, an inevitability given the fast pace of Gwinnett’s demographic transformation.

Strip mall with Latino businesses on Buford Highway in Norcross, Ga. Norcross is part of Gwinnett County, where Latinos surpassed 10,000 of the voting-age population, making Spanish ballots a requirement. Photo by Bita Honarvar for palabra

Literature explaining a language assistance program for voters is displayed at the Gwinnett County Board of Voter Registrations and Elections building in Lawrenceville, Ga. Photo by Bita Honarvar for palabra

“They were really hostile towards providing language access,” González said.

The arrival of Mexican workers to fill the construction needs of the 1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta and an accompanying housing boom fueled the growth of the Latino community in Gwinnett County and all of Georgia. The county has since become a hub for immigrants from Latin America and beyond, in part because of its affordable homes and easy highway access to Atlanta and elsewhere in Georgia.

However, the same white nationalist sentiments that González blames for the reluctant implementation of Section 203 requirements still linger. The arrest of a Venezuelan migrant, charged with the recent murder of a nursing student in Athens, Ga., has prompted anti-immigrant legislation in Atlanta and Washington while fueling fears of anti-Latino backlash.

Meanwhile, Zavala, the election specialist, embraces his work as a sort of mission. “I like to be an example for the good in others,” he said. “Doing things the right way or the best way possible.”

Sharon Padilla is a Honduran immigrant who works as a cashier at the Supermarket Guadalajara, a grocery store in Norcross. Padilla, 24, said she prefers Biden over Trump because she's uncomfortable with what she sees as Trump's anti-immigrant attitude. As for the opportunity for Spanish-speaking citizens in Gwinnett County being able to vote in their native language, "It’s good because that helps for the people who don't speak the English." Photo by Bita Honarvar for palabra

He’s part of a team that reaches out to Spanish-speaking voters at community events, keeps up with the inventory of written voting materials and maintains a glossary of Spanish-language voting vocabulary words to make sure these translations are consistent. The team also runs four language-equity groups, where community volunteers meet weekly over Zoom to discuss how to better reach voters who speak Spanish, Mandarin, Korean and Vietnamese.

Georgia — home to Atlanta, a city known as the cradle of the Civil Rights Movement — is now a battleground state. On presidential primary day, we talked to Zavala and other residents of Gwinnett County in Norcross, a city that’s nearly 40% Latino, about the issues that matter to them this election year and the changes that have happened around them. We met them in immigrant-owned businesses along a congested seven-lane road called Buford Highway, in the historic downtown and at a community center, as they cast their ballots.

Gail Bolton speaks to a visitor outside of the Best Friend Park polling location in Norcross, Ga., after voting in the presidential primary. Photo by Bita Honarvar for palabra

Forty years ago, when Gail Bolton and her husband moved into the Norcross home her father-in-law built, “that street was totally Caucasian,” she said. Now, “it is diverse with Hispanic and Asian and Indian.” Bolton, 69, has seen the city grow and change around her, and she supports the requirement that voting materials be offered in Spanish.

“It’s very helpful to have a knowledgeable voter, and if they can read it in their language, then they're going to be able to answer it truthfully,” she said. “Where if they don't know what it's saying in English, they may not answer the way they truly believe.”

A supporter of President Trump, Bolton said she voted in the presidential primary because “we cannot let Joe Biden win. I mean, our country will just go really, really south.”

Ana Villamil, left, speaks with poll workers at the Best Friend Park polling location in Norcross, Ga., as she arrives to vote in the presidential primary. Photo by Bita Honarvar for palabra

Ana Villamil and her two children came to the United States and settled in Norcross 36 years ago, fleeing drug cartel violence in Villavicencio, Colombia. When she first moved to Norcross, there were few Spanish speakers, which made her feel socially isolated. Now, she said, Spanish is “everywhere” and she likes that “especially because I like talking.”

Villamil, 70, worked more than 30 years babysitting for a white family who asked her to speak to their children only in Spanish, which made it tough for her to master English. She’s a U.S. citizen and appreciates that, for the past several years, she has been able to read voting materials in Spanish.

“I'm feeling much better because I can say, ‘you can do it,’” Villamil said.

She cast her vote for Biden because she doesn’t like Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies. She believes that under Biden, it should be easier for immigrants to become citizens.

Jocabed Montoya arranges quinceañera dresses at the Guadalajara Bridal Boutique in Norcross, Ga. Photo by Bita Honarvar for palabra

In a strip mall off Buford Highway, Jocabed Montoya ironed glittery appliqués onto a pair of white Keds inside the Guadalajara Bridal Boutique. A few months from now, the shoes will be part of a quinceañera ritual called the changing of the shoes. That’s when the birthday girl’s father removes his daughter’s sneakers or flats and slips her feet into high heels, symbolizing her transition into womanhood. The task carries special significance for Montoya; she lived in Durango, Mexico, when she turned 15 and did not have a quinceañera.

Montoya, 42, moved to Gwinnett County years ago. Though she’s still not a U.S. citizen, she pays close attention to presidential politics. “On the Latin news, they speak only about immigration and the economy,” she said.

She said the path to citizenship should be easier and that while indicators show a strong economy, she has struggled. “The food is higher every time,” she said.

Cynthia Foster leaves the voting station at the Best Friend Park polling location in Norcross, Ga., during the presidential primary on Tuesday. Photo by Bita Honarvar for palabra

Cynthia Foster, a retired entrepreneur, moved to Norcross from Florida five years ago to be closer to family. She showed up to vote at the community center with her partner and daughter and cast a ballot for Biden, moved by her concern about reproductive rights.

“I want my voice to be heard,” said Foster, 64. “I'm patient enough to wait for the changes to come.”

Mindful of “what my foreparents went through for the right for us to vote,” Foster, who is Black, described the Spanish-language voting materials as a fair way to ensure voting access to a new crop of naturalized U.S. citizens.

“We have a lot of people that immigrated over into our country,” she said. “So they’re coming here, they’re creating jobs for themselves and I feel like they’re coming here with a purpose.”

Hernan Mosquera, assistant manager and interpreter at the Best Friend Park polling location in Norcross, Ga., waits for voters to arrive to vote in the presidential primary. Photo by Bita Honarvar for palabra

Hernan Mosquera arrived at the Best Friend Park Gymnasium in chilly predawn darkness at 5:30 a.m on presidential primary day to set up and secure voting equipment. The site opened for voters at 7 a.m. It was his first time working the polls for the Gwinnett County Voter Registration and Elections Office and his day would be long — nearly 16 hours, the skies dark again when he left at 9 p.m.

A lanky 40-year-old, Mosquera sees working the polls as his patriotic duty. He has lived in Gwinnett County for seven years, emigrating from Colombia to join his mother, a naturalized U.S. citizen, and other family members. He took his oath of citizenship on February 27, 2021, at a naturalization ceremony not too far from the polling site.

“I'm really happy to have my American passport,” he said. “It’s perfect. That's one of my dreams.”

Mosquera believes that many Spanish-speaking citizens would be intimidated if voting materials were offered in English only. His job, in part, was to guide voters through the process, which includes interpreters who may go into the voting booth with non-English speakers.

“Now that I am a U.S. citizen,” he said, “I need to serve my country and I need to serve my county.”

—

Allison Salerno is an award-winning multimedia journalist based in Athens, Ga. She’s a seasoned reporter, whose work has been published in The New York Times and The Washington Post. She has also produced audio stories about farming, food, and social innovation, among other topics. You can find Allison on Facebook, X and Instagram @allisonbsalerno.

Other palabra stories by Allison Salerno: The Invisible Network, Finding Home, Conquistando un Hogar

Bita Honarvar is an independent photojournalist and visuals editor based in Atlanta. She also works as an image editor at Gravy, a quarterly publication from the Southern Foodways Alliance. There, she primarily commissions original illustrations, and also original photography, to accompany non-fiction stories, essays and poems. Bita spent the early part of her career at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, where she was a staff photojournalist and photo editor for 16 years. Her work there took her around the United States and abroad, including stints in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Iran. More recently, she was the senior photo editor at Vox.com. She is a member of the National Press Photographers Association and serves on the board of the Atlanta Photojournalism Seminar, the longest continuously-operating photojournalism conference in the U.S. @BitaHonarvar

Other palabra stories by Bita Honarvar: The Invisible Network, Big Data at School, “Big Data” en la Universidad

Fernanda Santos has focused her career on elevating the stories of underrepresented and misrepresented communities. She is a professor of practice at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication, a writing coach in the Poynter Institute’s Power of Diverse Voices and a co-writer of ¡Americano!, an Off Broadway musical based on the life of an Arizona Dreamer. Previously, Fernanda worked as editorial director at Futuro Media, contributing columnist at The Washington Post and staff writer at The New York Times. Fernanda got her start in journalism in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, her home country, and has reported in three languages, in Latin America and the United States. She’s the author of The Fire Line: The Story of the Granite Mountain Hotshots, and is currently at work on a memoir. She lives in and loves New York City. @ByFernandaS