A Lingering Infection

Deportees from the United States, their belongings in plastic bags, check in with customs in La Aurora International airport in Guatemala City. Photo courtesy of Guatemalan Migration Institute

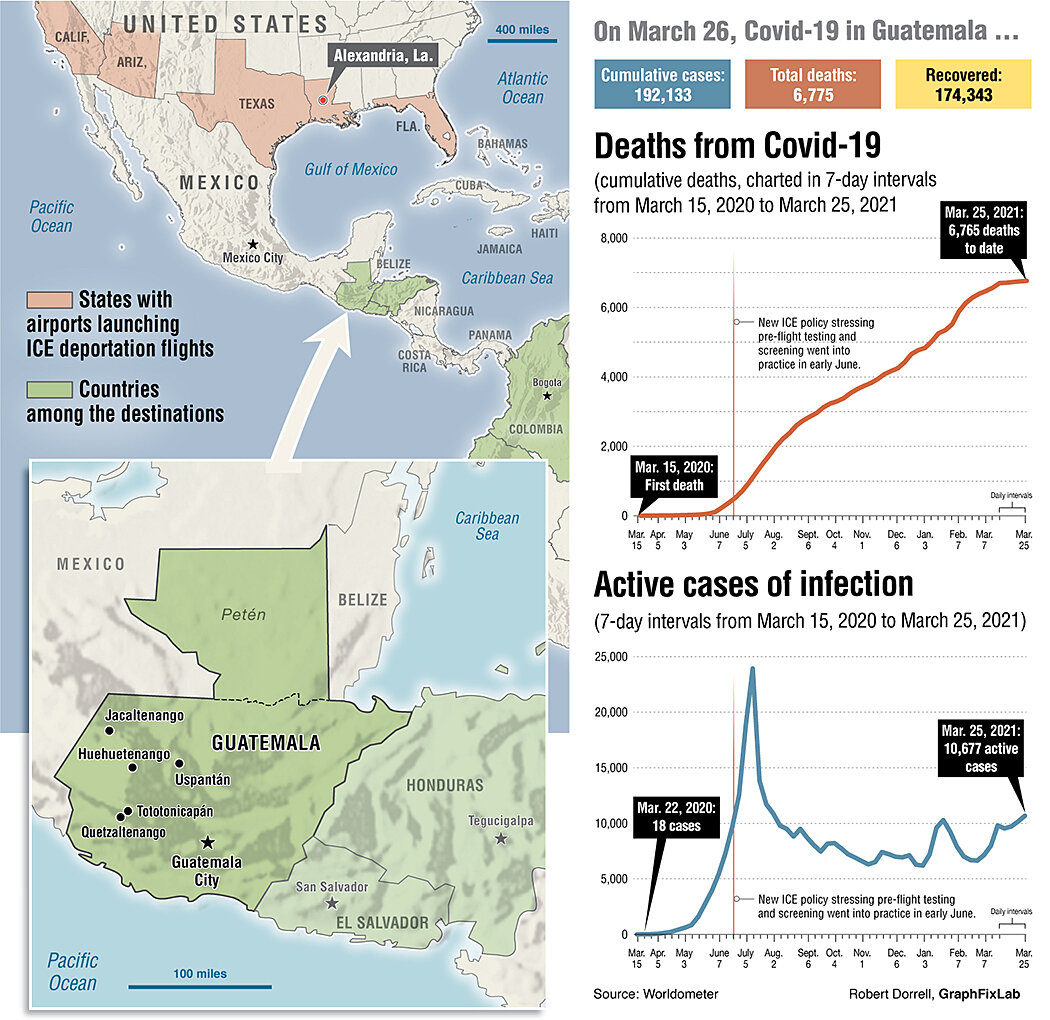

Guatemalans infected with COVID and deported from the U.S. aggravated the country’s coronavirus outbreak. They have faced stigma and neglect at home. In 2020, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement moved to stop exporting the virus. But documents in Guatemala say infected deportees continue to arrive in planes sent by ICE

Editor’s Note: Over the past year, palabra. has tracked the spread of COVID through vulnerable communities in the United States and Latin America. Our stories from Colombia, Brazil, Peru and Mexico have shown how inaction can fuel outbreaks and social conflict.

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Lea este artículo en Español

A year after individuals returning from Europe became Guatemala’s first COVID-19 positive tests and casualties, life at home for those who’ve lived through infections and illness continues to be marked by isolation and stigma.

Hundreds of those returning infected were exposed while in the custody of the United States’ Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency (ICE), which over the last year sent home at least 22,000 Guatemalans, according to the Guatemalan Migration Institute.

In spring 2020, ICE responded to complaints from health officials and politicians in Guatemala and other Latin American countries. The agency bolstered pandemic health protocols in its nationwide detention system, and ramped up pre-deportation COVID testing to keep infected deportees off Latin America-bound planes. Yet the infected have continued to arrive in Guatemala City, according to a review by palabra. of government health records.

At least 292 Guatemalans were sent home infected with the virus between May of 2020 -- when the new health protocols were established -- and October. Numbers for November and December of 2020, and January and February of 2021, have not been published.

Officials in Guatemala’s Migration Institute said many deportees have been allowed to recover from COVID infections in the U.S., like the 32 deportees who came home March 18 on a flight from Alexandria, Louisiana. But government health officials, speaking on background, insisted that infected Guatemalan deportees have continued to arrive in 2021.

For months, ICE officials have declined to address questions from palabra about the continued deportation of COVID-infected Guatemalan migrants, well after the agency said it would stop that traffic.

The Guatemalan government has also not raised new alarms over the continued flow of infected deportees. Apart from a brief suspension of deportee flights from the U.S. early in the pandemic, Guatemalan officials have said they are committed to receiving deportees, sending infected migrants to hospitals and others into temporary quarantine.

The day the pandemic came home

As of March 26, a year after president Alejandro Giammattei announced the first infection in the Central American nation, the country already had 192,133 cases and 6,775 deaths.

Covid reaction was swift in Guatemala after deportees began arriving from the United States. Photo via Sutterstock

In those numbers is what many Guatemalans say is a story of U.S. carelessness that has aggravated the pandemic: According to the Directorate of Integrated Health System, the first three cases of infected Guatemalan deportees from the U.S. were men who arrived on a flight from Texas on March 26, 2020. A subsequent flight in April 2020 carried 76 migrants, mostly from Texas detention centers. Of those, 71 tested positive for the coronavirus in Guatemala City.

From one nightmare to the next

María Gómez was one of those who spent time in isolation upon her return last summer. She has struggled to resettle after her dream of migration to the United States abruptly ended when she crossed, on foot, from Mexico and was surprised by border patrol agents in the Arizona desert.

Gómez spent four months detained in McAllen, Texas.

She arrived -- virus free -- at Guatemala City’s Ramiro de León Carpio shelter at the end of July 2020. The 160,000-square-foot space had once served as temporary housing for athletes from around the world, in town for international sports competitions.

Gómez, 26, was aboard an “anguishing,” four-hour flight from Alexandria, Louisiana, with another 100 men, women and children who had been held in ICE detention centers across the United States.

Gómez said she was tested for COVID-19 before boarding her flight, but ICE never gave her a clearance, on paper, that she could use to assure the doubters in her neighborhood in Guatemala. She was tested again in the Guatemala City shelter and confirmed as virus-free -- and was issued a document saying so.

María Gómez was interviewed outside the facility where she served her quarantine, after being deported by ICE. Photo by Oscar García

“(In Guatemala) they gave me this paper saying that I am not sick. I will show this to anyone who asks for it,” Gómez said upon her release from the sports complex, six days after her flight touched down.

Gómez was lucky. In all of July 2020, 98 detainees tested positive on landing.

What Guatemalans said was negligence by U.S. immigration officials was repeated throughout the summer and fall of 2020.

Despite those complaints, and after briefly denying landing rights to U.S. immigration flights, Guatemalan officials built makeshift hospitals for infected and sick deportees. The government allowed flights to resume after the U.S. threatened sanctions against countries that “deny or unreasonably delay the acceptance of their citizens.”

Fear of stigma

Rogelia Cinto was on the same flight as Gómez, complaining along the way that her “head was spinning” as she wondered how her family and neighbors would receive her in her village in Huehuetenango state, 135 miles west of Guatemala City.

Her concern began when she was still in detention in the U.S. She’d learned that a cousin, who was deported earlier, had been locked up in his hometown for several days -- even though he was virus-free -- in a facility set up by the local Community Council for Urban and Rural Development (COCODE).

Established by the Guatemalan Congress in 2002, COCODEs are found around the country. The neighborhood groups promote community development. But since March 2020 they have been controlling access to many small towns to prevent the spread of COVID-19 infections. Outsiders are denied entry.

Rejection by neighbors and family was a common topic of conversation among deportees at the Guatemala City shelter. Cinto said it haunted her last summer as she boarded a government-provided bus destined for the country’s rural western departments of Tototonicapán, Quetzaltenango, Huehuetenango and Quiché.

“We learned from other fellows that they don’t want us,” said another deportee, Eduardo, who was on the flight with Cinto and Gómez. He declined to give his last name, out of fear of retaliation. “They think that because we come from the United States, we bring COVID-19. (But) this illness is everywhere.”

Eduardo spoke as he was boarding a bus that would embark on a 225-mile trip to his town, Chinchillá, deep in Guatemala’s Petén region. He promised a family member traveling with him that he would deal with “any situation”; he would not allow himself to “be humiliated” once he got home.

Not all villages in Guatemala have rejected deportees sent home from the U.S. This sign welcomes “migrant brothers and sisters” with open arms. Photo courtesy of Uspantán municipality.

According to Osmar Tello, mayor of La Unión Cantinil in Huehuetenango state near the Guatemalan border with Mexico, rejection of deportees was widespread a year ago. Tello said he was threatened by neighbors after he allowed some deportees to return to their homes.

“(They said) if someday the pandemic got here (La Unión Cantinil) it would be my fault,” said Tello.

This convinced many deportees to return quietly, asking families to avoid neighbors, or offer vague responses about their health and their whereabouts.

In contrast, in shelters in Jacaltenango, Huehuetenango and in Uspantán, Quiché, mayors and neighbors said they have welcomed deportees.

“We are very willing to support our migrant brethren because they have been a key part of the economy of Jacaltenango and of Guatemala. They deserve decent treatment,” said Juan Antonio Camposeco, mayor of Jacaltenango. He added that in the United States, there are about 13,000 people from Jacaltenango, or about 18% of the local population.

A daily humiliation

Yudy López said she’s reminded daily of her humiliation in custody in the U.S., and the distance now kept by neighbors and family since she returned to Guatemala City.

In 2020, López spent months in ICE custody, trying, and failing, to convince authorities to allow her to apply for asylum. She recalled spending too much of her brief time in the U.S. in handcuffs; she said she was even handcuffed on her deportation flight last summer.

Yudy López with her belongings, in August, 2020, after being quarantined in Guatemala City. She avoided illness, although she flew home from the U.S. on an ICE flight that yielded several cases of COVID-19. Photo by Oscar Garcia

Things got worse, she said, after she arrived in Guatemala City and was released from the shelter.

In August 2019, she had left her belongings with a neighbor in Guatemala City before setting out for the U.S.-Mexico border. After her deportation -- and her stay in quarantine in the sports complex -- she revisited the neighbor to pick up her things. But the property owner did not let her in, insisting she not return for 10 more days.

“When I turned around to leave, the lady soaked the door in chlorine, because I had leaned on it while speaking with her,” López said. “I was furious and asked her why she used the chlorine if I (wasn’t sick).”

She recalled that when she was quarantined in the capital city’s Ramiro de León Carpio shelter, Guatemalan authorities and representatives of various social organizations came to interview her. They asked her why she left her country in the first place, and they took down her name and phone number before promising to help her get re-established in Guatemala City. No one has called, she said.

In the seven months since she came home aboard a flight with sick deportees, she’s felt ostracized by neighbors. She can’t find a decent job now, she added.

López said she feels blessed for having avoided becoming sick on her trip home, which began a year ago at the Joe Corley ICE detention center in Conroe, Texas. She spoke of spending five months with 11 women of various nationalities as cellmates, amid what appeared to be improvised health protocols by ICE.

“We were all kept together … . Those who ended up with the virus were dressed in orange. They were the ones who would faint, then (be) moved to the next room. When (COVID-19) started, they put us all in one room and told us that they would isolate us because one of us in the group began to feel sick with symptoms of sore throat, fever and cough. They took her out and isolated her.”

Yudy López prepares some of the snacks she sells on weekends in downtown Guatemala City. Since her deportation from the United States, during the coronavirus pandemic, she’s not been able to land a steady job. Photo by Oscar Garcia

On a recent Saturday López talked as she walked near Elena Avenue in Guatemala City’s colonial downtown, selling snacks to pedestrians. It’s her weekend routine, earning her just enough to cover basic expenses.

During the week, she’s paid cash to wash other people’s laundry, from before dawn until the late afternoon. Her feet are swollen by the time she gets home.

Thinking about the last year leaves her sad, Lopez said. She longs for formal employment, but she knows that the pandemic has made full-time work “a complicated issue.”

“I (think about) the opportunities I would have had in the United States if I had stayed there, working. I went to fight for my children’s future. They are young. But the (U.S.) immigration service frustrated my dream,” López said, gasping a bit while she walked, holding her plastic bags with snacks for sale.

---

Oscar García is an editor at the Nuestro Diario newspaper in Guatemala City. He is a graduate of the University of San Carlos de Guatemala, and a former professor of the Faculty of Communication Sciences of the Mariano Gálvez University. Three decades ago, he started out as an editor and reporter at the Guatemala Flash radio newspaper and the Diario Al Día newspaper.