A Toxic Trail

Donald Moncayo, a community leader from Lago Agrio, has witnessed the arrival of Texaco and the onset of oil exploitation in the region since he was just 13 years old. Photo by Andrés Cornejo Pinto for palabra

Big Oil’s Legacy: In Ecuador, Indigenous communities cope with pollution and illness

Haga clic aquí para leer el reportaje en español.

“In a'ingae, my native language, the words oil, contamination, and cancer did not exist until Texaco arrived on our lands,” says Don Arturo, an elder among the A'i Kofán Siangoé people, one of Ecuador's 11 Amazonian communities. The A’i Kofán worldview is based on an intimate relationship with nature and its environment, and a strong spiritual connection with its ancestral territory.

Don Arturo lives in Dureno, a community located on the banks of the Aguarico River. The river crosses the province of Sucumbíos in the northwestern reach of the Ecuadorian Amazon, near the border with Colombia. To get to his home, built with materials such as wood and zinc, you have to cross the river by raft. Don Arturo says that when he was a child, the river was crystal clear and full of fish, which allowed him and his community to make a living. In those days, everyone in the community was healthy and led quiet lives.

As Don Arturo's memories gradually fade, he says he’s compelled to remember and share his story. At 72, nostalgia takes him back to when he was 13 years old. The petroleum company Texaco (now Chevron) had just arrived on his land. "White men arrived in the Amazon with huge machines that razed the forest and the community's land."

To this day, he harbors terrible memories of having witnessed abuses by company workers, worst among them the rape of an indigenous woman.

Don Arturo, an A'i Kofán indigenous man, resides along the banks of the Aguarico River in Sucumbíos province, in the Ecuadorian Amazon. He lives with the harsh consequences of oil industry exploitation. Photo by Andrés Cornejo Pinto for palabra

In a soft voice and broken Spanish, he recounts how, from one moment to the next, neighbors noticed that cattle began to die, and his relatives suffered from unfamiliar diseases.

For him and his people, the arrival of the petroleum company meant a break in their way of life and the loss of everything they knew and loved.

Don Arturo now has prostate cancer. The Aguarico River, once crystal clear and full of fish, is polluted and empty. These days residents must leave their land to buy food in the city. The life he knew is just a memory.

The story of Don Arturo is like that of thousands of Amazonian indigenous people living with the consequences of oil exploitation in Ecuador, and neglect and abandonment by the government. Thirty years have passed since the community began to demand justice and struggle against official impunity and a hostile and precarious environment.

CHEVRON IN ECUADOR: A PAINFUL HISTORY

Almost 60 years ago, U.S.-based Texaco Gulf arrived to operate oil wells in the Ecuadorian jungle. The company’s time in Ecuador lasted until 1990. A decade later, the company became part of Chevron.

Chevron evokes in the memories of many Ecuadorians and environmental organizations that of one of the worst environmental disasters in history. According to documents from Ecuador's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Human Mobility (MREMH, in Spanish), the company failed to comply with proper environmental protocols and dumped millions of gallons of toxic water and oil residue into rivers and streams adjacent to oil wells, spreading pollution across some 400,000 hectares.

According to a 2008 study, environmental damage was followed by a decline in the health of the local indigenous population, including children, who suffered from chronic and congenital diseases that in many cases led to death.

The document found that those who live in places surrounding the exploited area, in the provinces of Orellana and Sucumbíos, have three times more cancers than the rest of the country. The figure is higher when compared to communities in the same Amazon region not exposed to contamination. It is estimated that around 30,000 people were affected, belonging to different indigenous groups and farming communities.

A gas flare in Lago Agrio, a common device used in the oil-rich regions of the Ecuadorian Amazon to burn off excess gas and extraction waste. In the photo, Donald Moncayo, a prominent advocate in the fight for justice against Texaco Chevron's pollution. Photo by Andrés Cornejo Pinto for palabra

Donald Moncayo, a community leader from Lago Agrio and spokesperson for the organization Union of Those Affected by Texaco (UDAPT, in Spanish), remembers clearly the tragic experience of his mother, who suffered three miscarriages. Moncayo says that happened after Texaco arrived. He says he’s convinced there were more in the same community. A 2004 investigation found that the risk of having a miscarriage was more likely in communities near oil wells, versus those free of contamination.

But the tragedy did not end there. Cancer was discovered in residents of the area. During those years, he recalls, residents were being led to believe that the oil was medicinal. Some neighbors rubbed their bodies with the traces of oil that began to appear in the forest, believing that this would heal various ailments. They even walked barefoot over black puddles of oil, convinced that this black liquid was a source of healing.

The environmental catastrophe only became known to the public around the 1990s. It was then that Ecuadorian lawyer Pablo Fajardo, later a recipient of the Goldman Environmental Prize, filed a lawsuit in a New York court, but the corporation successfully fought to have the dispute moved to Ecuador.

In 2011, an Ecuadorian judge ordered Chevron to pay as much as $9 billion in compensation to communities affected by contamination in the Lago Agrio region in the Ecuadoran Amazon. Chevron refused to pay, as it had already ceased operations in the area. Over months, palabra made multiple efforts to contact Chevron for this story. The company has not responded.

But since the judgment, Chevron questioned the "legitimacy" of the verdict, arguing that the ruling was the result of fraud and bribery. The petroleum company claimed that it complied with proper environmental care requirements and attributed the damage to Petroecuador, the Ecuadorian company that took over oil development in the region after Chevron left Ecuador.

But the damage was indisputable: vast expanses of jungle were left covered by toxic black oil. The agony of residents with unknown diseases was clearly visible, and a number of studies and professional results attested to the damage.

None of that, however, was enough to obtain justice or reparations.

After the first ruling in an Ecuadorian court, the issue was transferred to U.S. courtrooms. In a new trial, former Ecuadorian judge Alberto Guerra testified that he “had been bribed by lawyer Steven Donziger to rule in favor of the victims of the petroleum company.” These statements caused U.S. federal judge Lewis A. Kaplan to rule in 2014 that the Ecuadorian judgment against Chevron was because of fraud.

Years later, former judge Guerra retracted what he had said in U.S. court, admitting that it was Chevron who had given him $2 million.

To discredit the ruling against them, the oil company launched an international smear campaign against the communities, their lawyers, and judges in Sucumbíos. Chevron also started international arbitration to place blame for the contamination in the Amazon on the Ecuadorian government.

Community lawyer Julio Prieto asserts that since 2004, Chevron has initiated claims seeking to have the Ecuadoran government take charge of the environmental cleanup.

CHEVRON’S VERSION

The oil company says that the alleged environmental control failures occurred in previous decades and that the problem of decontamination is the responsibility of the Ecuadorian oil company that took over after Chevron left.

In 2009, Chevron took the case to the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague in the Netherlands, asserting that it had not received a fair hearing in Ecuador, and that the country violated the Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) signed in 1993 between Ecuador and the United States. In 2017, the international court ordered Ecuador to annul the 2009 ruling and compensate the oil company for legal expenses.

In 2020, a ruling from the International Court of Arbitration on the Chevron v. Ecuador case favored the oil company, and on June 28, 2022, the Court of Appeal in The Hague affirmed the decision. The result was a dramatic turnaround: the petroleum company originally ordered to pay for the environmental damage was now the plaintiff and allowed to file claims to recoup legal costs. The ruling drew sharp criticism from some legal observers who called it an affront to justice and a setback in the fight against environmental pollution.

Donald Moncayo, a community leader in Lago Agrio and spokesperson for the Union of Affected People by Texaco (UDAPT), reflects on how his mother endured miscarriages as a result of oil pollution, which deeply alarmed the community. Photo by Andrés Cornejo Pinto for palabra

Pressure from the UDAPT — and an international media campaign led by environmental activists — led to an appeal by Ecuador on September 27, 2022 in The Hague.

A decision is pending.

Despite resisting blame, Chevron has repeatedly said it had indeed helped clean up around its former operations in the Amazon. But Moncayo says no such thing ever happened. Instead, it has been the state-owned oil company, Petroecuador, that has cleaned up some pools. The "remediation" carried out by Chevron took place between 1995 and 1998, according to Moncayo. It consisted of collecting the upper part of the spilled oil, the thickest part, and covering it superficially with dirt.

However, residents observed that liquid oil continued to seep into the jungle. "All the mud from the drilling and the toxic liquid remained in the pools," says Moncayo. Chevron claims the pools belong to the government-owned company that took over its operations in the region. Aerial photos certified by Ecuador’s Military Geographic Institute were obtained from 1976 when Texaco — not Petroecuador — operated in the region.

POLITICAL IMPACT IN ECUADOR

The lack of a legal defense strategy, free of political fluctuations, has also affected the fight against pollution in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Various federal administrations have held contradictory positions on environmental protection in the country’s Amazon region. This lack of coherence in public policies has generated uncertainty and mistrust among people still living with the pollution.

Protesters paint an oil pipeline in Lago Agrio, demanding justice for Texaco's Chevron oil pollution. Photo by Andrés Cornejo Pinto for palabra

A tragic example of this is how two presidents — former allies turned political enemies — fought over credit and blame for the pollution and its consequences: During the administration of President Rafael Correa (2007-2017), the government led protests against the oil company with “The Dirty Hand of Chevron” campaign in 2014. Years later, President Lenín Moreno accused Correa of misusing public funds for that campaign.

After Correa, interest dwindled amid the political contradictions. In 2022, the Ecuadorian government finally appealed the ruling in The Hague.

According to Manuel Pallares, a biologist and environmental educator who has lived with the Secoya people, another of those most affected by the contamination, "The biggest mistake in the Chevron case has been its politicization." Pallares believes that this case should not have been used by any party or political line, since it is a violation of human rights and an environmental crime.

THE CHEVRON - DONZIGER LAWSUIT

Despite the magnitude of the pollution and the health consequences for residents in this part of Ecuador’s Amazon, for many years the case was practically unknown to global public opinion. In 2021, the Chevron case rose to prominence again, especially in the United States, after the Chevron v. Donziger lawsuit.

Steven Donziger was part of the legal team that helped win the original claim against Chevron. Years later, Chevron initiated legal action against Donziger, which led to him being disbarred. He spent almost three years under house arrest, accused of contempt of court.

Critics said the trial against Donziger was an alarming example of corporate persecution. U.S. media coverage sparked support for Donzinger from activists, celebrities, Nobel laureates, and politicians including U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

Ecuadorian immigrants in New York also became active, organizing rallies and marches to demand Donziger's release. Among the protesters were many who had migrated from affected areas in the Ecuadorian Amazon – indigenous men and women who said they suffered because of the "black gold" and its toxic waste. The indigenous leader Lino Wamputsrik, because of the precariousness of his life in the Amazon, decided to migrate to New York from his native jungle to what he called a "concrete jungle," where he continues to demand justice for his community.

CURRENT REALITY

After the departure of the U.S. oil company in 1990, around 880 pools with toxic waste were abandoned in the Ecuadorian Amazon. At present, elderly residents of the area are being affected by diseases that have never before been diagnosed in the region, according to residents and the community’s Environmental Clinic doctor Adolfo Maldonado. The list includes various cancers, with the most common being skin and liver cancer and leukemia.

Don Arturo is in the midst of a battle against prostate cancer. In regions marked by oil exploitation, such as Lago Agrio, people grapple with comparable health challenges. Photo by Andrés Cornejo Pinto for palabra

According to Moncayo, despite the seriousness of the situation, the Ecuadorian government does not provide preventive measures to limit exposure to contaminants, or basic services to the affected communities. Residents say there is also inadequate medical care. palabra reached out to health officials to corroborate this information, but as of publication time had not received a response. Data provided by Ecuador’s Ministry of Public Health show cancer in the affected area is scarce, since officially only 31 cases have been registered in the Siekopai community, one of the most affected. However, Moncayo explains that the historical lack of health monitoring in the Amazon by public institutions misses many cases in clinics and hospitals not monitored by the government.

The hospital in Lago Agrio, the provincial capital of Sucumbíos, where oil companies still operate, does not have equipment to treat catastrophic illnesses. That means Don Arturo, one of the Kofan indigenous people who suffers from prostate cancer, must travel hundreds of miles to the capital city of Quito for his chemotherapy. Some of the drugs he needs are so scarce that he buys them from Colombia on the black market.

He says that the damage that Big Oil left around his home goes beyond the environmental. It has affected his culture. Fewer people now live in the Kofán indigenous region. Traditions have disappeared. He says he’s lost hope; he just wants a cleanup so his grandchildren don't share his fate. “There is nothing to do anymore, I will soon die; my culture will never come back,” he says in a soft, slow voice.

THE CANCER LEGACY

According to Miguel San Sebastián, a specialist in environmental epidemiology, an analysis titled the Yana Curi Report found that women living in communities near oil wells have a 2.5 times higher risk of miscarriages compared to those who live in uncontaminated communities. There is also a higher risk of death from cancer – especially stomach, liver, and skin – among men in the area.

Several decades have passed since the start of the contamination, and people affected by government and corporate negligence have yet to receive reparations. It’s dragged on so long that it’s become an intergenerational crisis.

Emilio Lucitante, a 105-year-old elder and member of the Siekopai nationality, is one of the original plaintiffs against Texaco. Photo by Andrés Cornejo Pinto for palabra

Don Emilio Lucitante, 105 years old and a member of the Siekopai community, lives three hours from São Paulo, Brazil. He is one of the original plaintiffs in the Chevron-Texaco case. In his community, several people have died of cancer, and others with little income treat themselves. They’ve received no help from oil companies or the Ecuadoran government.

Lucitante lives in perilous conditions with his wife, son, daughter-in-law, and 5-year-old grandson. There is a noticeable chemical in a nearby river, the family says, and the little boy has persistent spots on his skin. His father, Orlando Lucitante, has taken the boy to doctors in Quito, but the skin condition has not improved. The family fears he may have skin cancer.

Don Emilio has said he’s been threatened for his participation in the lawsuits against the oil companies. He signed various documents and writings supporting the communities’ complaints. But he’s also learned that the attorney general's office may be investigating him for allegedly bribing Nicolás Zambrano, a former judge of the Sucumbíos provincial court. Despite the challenges, Don Emilio says he is not afraid. He will continue to fight for his family, he said.

THE TOLL

According to advocacy groups like Amazon Watch and INHRED, the high levels of chemicals such as cadmium and lead caused congenital anomalies and cancer in hundreds of people who live in areas exposed to oil contamination such as Sucumbíos and Orellana, in the Amazonian provinces of Ecuador. Reports from these organizations state that Texaco contaminated water in Ecuador with carcinogenic and volatile organic compounds.

A 1994 study from the Center for Economic and Social Rights found a risk between 12 and 1,000 times higher than what is acceptable in the United States. Oil exposure is linked to adverse health problems, including cancer, respiratory diseases, birth defects, and miscarriages. In addition, Texaco — according to the same study — withheld information about its environmental impact. The high-level studies underscore what local activists have long claimed: the emergence of cancer as a leading health threat is due to petrochemical pollution.

A study from 2002 to 2008 on 471 patients and published in the Scientific Research Journal explored the relationship between cancer cases and oil exploitation in the Ecuadorian Amazon. It revealed that the Napo and Sucumbíos regions had the highest cancer rates, with female genitourinary tract cancer being the most common.

Based on a report from Registro Biprovincial de Tumores and UDAPT, two out of every three patients are women. Already, 132 patients have died. The three most lethal cancers are cervical, breast, and leukemias and lymphomas.

A documentary produced by the Environmental Clinic and Ecuadorian filmmaker Pocho Álvarez depicts how deaths have recently increased because of a lack of specialized doctors, insufficient early diagnosis and proper medicines, and the difficulty of access to chemotherapy.

An oil spill, a frequent result of oil extraction, poses a significant environmental threat to Amazonian communities. Photo by Andrés Cornejo Pinto for palabra

“Seventy-two percent of the cancer cases registered in the Amazon affect women and that is another form of aggression and gender violence,” said Pablo Fajardo, a lawyer for the plaintiffs. "Isn't that a genocide?" asks Moncayo, who insists on calling the pollution and health crisis a crime against humanity.

The fight has not been easy and has claimed the lives of indigenous leaders such as Eduardo Mendúa. In February 2023, Mendúa, a member of the Kofán Sucumbíos community, was shot dead at point-blank range in his home while protesting Petroecuador's oil extraction in the Kofán territory. The community demanded an investigation and called out armed attacks of local indigenous people by workers of the Ecuadorian oil company. The Ecuadorian government has ordered an investigation into Mendúa's murder.

COMMUNITY SOLIDARITY

For environmentalists, the story of oil and Ecuador’s Amazon is a painful lesson on the human impact of ignoring the environment and the voices of residents.

Global oil companies are well-documented culprits of climate change. Yet drilling continues at a profitable rate for the industry, even as it has yet to lead to any level of prosperity for the inhabitants of the Amazon region, where more than half of the residents are poor and do not have adequate sanitation, drinking water, and an education system.

Scientists warn that the Amazon, weakened by deforestation, exploitation of natural resources, and climate change, could become a grassland.

Indigenous communities in the Amazon rightly say they are guardians of a priceless treasure: the largest tropical forest in the world.

Until now, community residents say, their ray of hope has been the only alternative that has brought actual help and support for those affected by oil contamination, which has been community solidarity and an increase in residents’ organizing.

The odds are against them but despite their slim chances, members of groups and so-called “Reparation Committees” in some communities have reached agreements with charities to provide free medical care and donations to cancer patients.

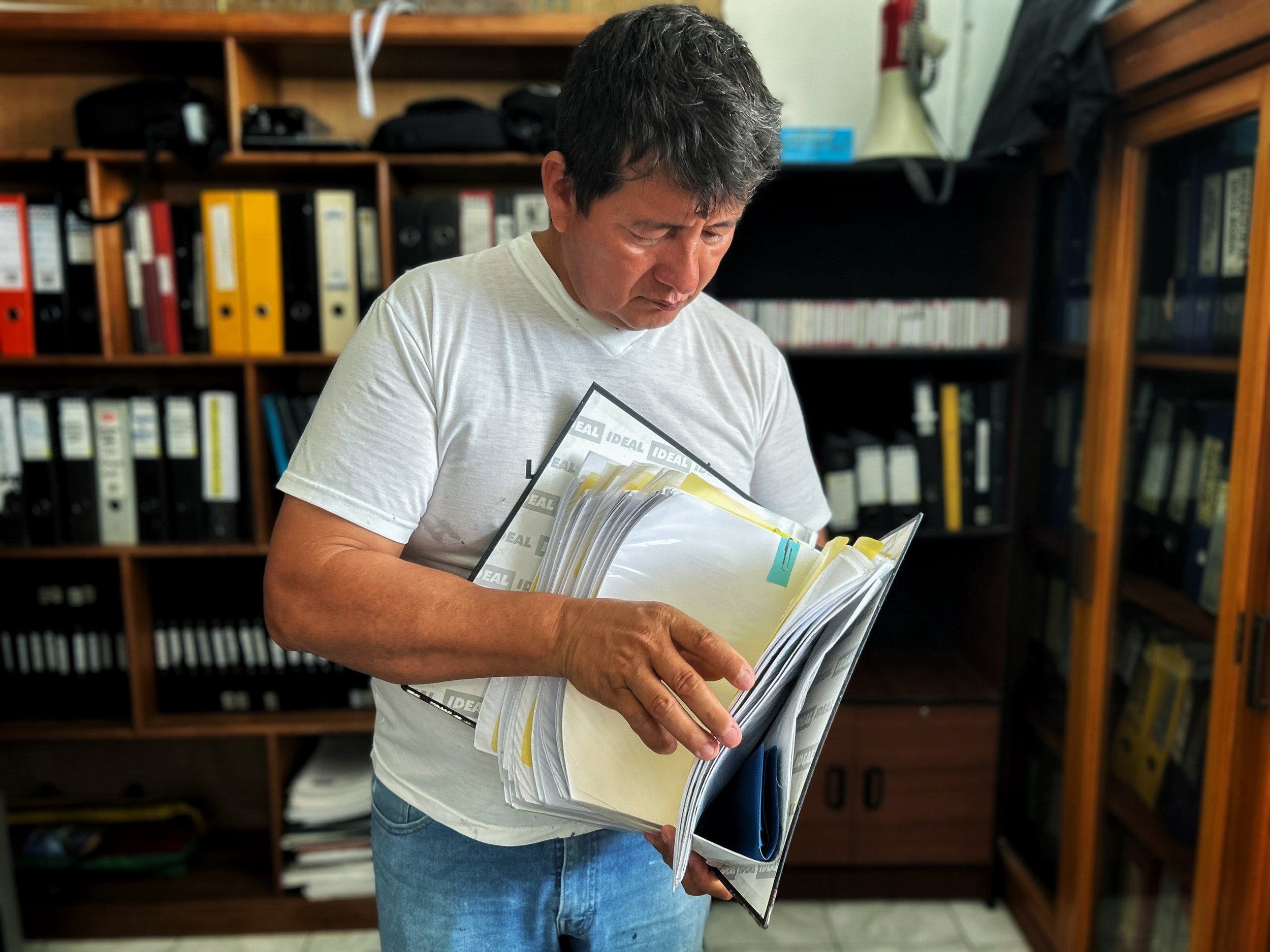

Donald Moncayo, leader of the Union of Affected People by Texaco Chevron (UDAPT), keeps decades of records and documents in his office from a 30-year legal battle. Photo by Andrés Cornejo Pinto for palabra

Additionally, a group — mostly women, calling themselves "therapists," has stepped up to accompany patients throughout the imposing journeys and trajectory of their disease and difficult treatment. These counselors have received training in alternative therapies thanks to the support of the Esculapio Technical Institute and its "Community Links" program.

Communities have also stepped up where the government and oil companies seem inactive. They’re doing their own land remediation, by hand in some places, over long days and despite exposure to biohazardous waste.

So that oil contamination is not forgotten, Moncayo has since 2003 been carrying out what he calls “Toxic Tours,” — free expeditions to what was Field 46, where Chevron operated and where the contaminated and unremediated pools remain, to raise awareness and tell the world what happened there.

The leader of the fight against Chevron says he has received threats on several occasions, as have many of his neighbors. Still, despite years of frustration, Moncayo maintains the hope that one day the community will find justice and his descendants will be able to once again swim in the rivers without fear of disease.

—

Gabriela Barzallo is a journalist based between New York City and Ecuador. Her work covers issues related to human rights, the environment, politics, social justice, and solutions in Latin America and its connection to the U.S. She has been published in Al Jazeera, El País, BBC Future, among others. Additionally, she is a climate fellow for the Solutions Journalism Network.

Andrés Cornejo Pinto is a non-fiction filmmaker based in Ecuador whose work as a director has been screened at festivals worldwide, including IDFA, HOT DOCS, BUSAN, EDOC, and SHEFFIELD. He is currently producing the documentary "Ozogoche.” Andrés has a degree in film from ESCAC (Barcelona) and a master's degree in film directing from Docnomads (Lisbon, Budapest, Brussels). In addition, Andrés is a professor at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito.

Ricardo Sandoval-Palos is palabra’s founding editor. He is the Public Editor for PBS, an intermediary on ethics, integrity and standards between the broadcaster’s audiences and its creatives and journalists. Ricardo is an award-winning investigative reporter and editor. His reporting in Latin America earned awards from the Overseas Press Club and the InterAmerican Press Association. He’s also co-author of the biography, “The Fight In The Fields: Cesar Chavez and the Farmworkers Movement.”

Patricia Guadalupe, raised in Puerto Rico, is a bilingual multimedia journalist based in Washington, D.C. She has been covering the capital for both English and Spanish-language media outlets since the mid-1990s. She previously worked as a reporter in New York City. She’s been an editor at Hispanic Link News Service, a reporter at WTOP Radio (CBS Washington affiliate), a contributing reporter for CBS Radio network, and has written for NBC News.com and Latino Magazine, among others. She is a graduate of Michigan State University and has a Master’s degree from the Graduate School of Political Management at George Washington University. She specializes in business news and politics and cultural issues. She is the former president of the D.C. chapter of NAHJ.