Only the Beginning

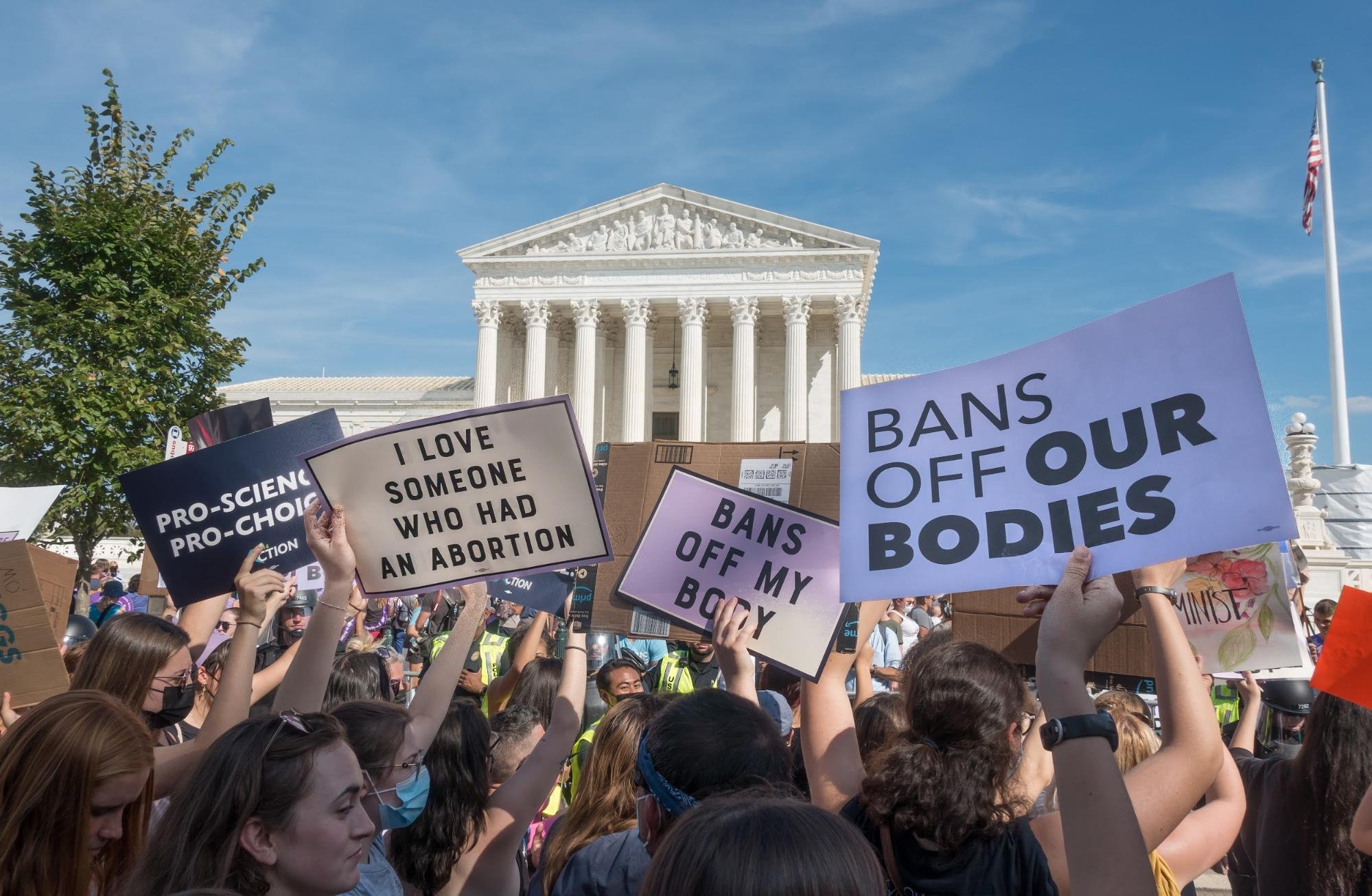

Months before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade and weeks after Texas banned abortions after six weeks, protestors descended on the U.S. capital during the Women's March to demand protection for reproductive rights. Washington, DC. Oct. 2, 2021. Photo via Shutterstock

Anti-abortion advocates don’t just want to criminalize abortion. Their strategy is to isolate the person seeking an abortion by targeting everyone that makes such care possible, whether it’s providers, friends — or journalists

Editor’s note: This Op-Ed is jointly published in partnership with Prism.

In the weeks since the Supreme Court issued its decision in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case that overturned Roe v. Wade and struck down our Constitutional right to abortion, the country has turned into an even more hostile place for marginalized people.

The risk of criminalization is so great that abortion funds have paused operations in states with trigger bans and laws that target people who provide abortion support. In states like Arizona and Texas, which have some of the largest undocumented populations in the nation, providers have stopped offering abortion care or packed up and moved to neighboring states, leaving undocumented people who cannot risk Border Patrol checkpoints with virtually no options. In effect, the Supreme Court ruling that the right to abortion is not "deeply rooted in this Nation's history or tradition” has strapped a ticking time bomb onto other fundamental human rights. How long before right-wing lawmakers come for contraception? How long before they come for interracial marriage and gay marriage? How will this ruling be used as justification to further whittle away at trans rights?

Abortion experts knew that overturning Roe would be a slippery slope. Harder to anticipate was how quickly the ruling would affect First Amendment rights — a gravely serious issue that should concern every newsroom operating today.

Last month, Prism editor-in-chief Ashton Lattimore reported on new anti-abortion model legislation released by the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC), one of the oldest and most powerful anti-choice groups in the nation. The multimillion-dollar organization not only helps elect anti-choice lawmakers but also shapes and influences state laws—and hopes that state legislatures nationwide will soon adopt its new model legislation that would subject people to criminal and civil penalties for “aiding or abetting” abortion. This includes “hosting or maintaining a website, or providing internet service, that encourages or facilitates efforts to obtain an illegal abortion.”

As Lattimore noted, the text offers no guidance on how broadly or narrowly the provision might be interpreted. Take, for example, a piece of reporting our newsroom published last year about accessing abortion medication by mail, or this reporting about abortion doulas navigating criminalization in a post-Roe world that concludes with a series of helpline numbers for confidential abortion support and legal aid. Does this constitute aiding and abetting abortion? As residents of the U.S., we know our right to abortion care has been stripped away. As journalists and editors, it would also be helpful to know if we are subject to draconian laws that place newsrooms in legal crosshairs for producing evidence-based reporting on abortion.

Pro-Choice protestors gather at the "Bans Off Our Bodies" rally at the Pennslyvania State Capitol to protest Texas' anti-abortion laws. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. October 2, 2021. Photo via Shutterstock

Even before the Supreme Court ruling, there was evidence of abortion information censorship. Jezebel reported last month that in states set to ban abortion when Roe fell, Google appeared to actively sabotage people’s searches—giving results for anti-abortion “crisis pregnancy centers” in searches about abortion care. A study from the Center for Countering Digital Hate found that in Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Texas, Oklahoma, and Wyoming, a whopping 37% of Google Maps search results for abortion care led to crisis pregnancy centers. To the unknowing, these faith-based organizations at first appear to be clinics, but soon it becomes apparent they don’t actually offer abortion services. For decades, these deceptive fake clinics have received tax payer money to disseminate dangerous health care misinformation that targets low-income pregnant people for the sole purpose of dissuading them from accessing abortion care.

Our newsroom has not been immune to Google’s harmful practices. Even though Prism has a Google Ads grant that allows us to run free ads that use keywords highlighting our most prominent coverage areas, the search engine blocked and denied our ads that used keywords like “abortion” and “abortion rights.” Even more chilling, in the immediate aftermath of the Roe decision, Instagram and Facebook began removing posts about abortion pills, including those that noted that the medication mifepristone could be obtained through the mail. Users who tried to repeatedly post about abortion medication were banned. Abortion Finder, a website that allows people to search for care providers, was also suspended from Instagram. The account was restored after a tweet about the incident went viral.

Abortion censorship is well underway, and if states adopt the kind of model legislation proposed by the NRLC, it would be a striking blow to the First Amendment and would prevent newsrooms from producing accurate, reliable information about abortion when it’s needed most. It would also have dire consequences for people in need of abortion care — an overwhelming percentage of whom are low-income Black and Latinx women who already have children.

The anti-abortion movement shaping our nation’s abortion laws have a clear goal: to create a terrifying and isolating environment for people seeking abortion care

There is a recurring theme in the most recent anti-abortion legislation, which does not target the person seeking an abortion, but everyone on their periphery who makes the care possible. This includes health care providers, abortion doulas, and abortion funds. This trend largely began with Texas’ Senate Bill 8, which was signed into law last year by Gov. Greg Abbott. Even before abortion was banned in the state as a result of the fall of Roe, SB 8 severely restricted abortion by banning the procedure once electrical activity in the embryo was detected, which occurs at about six weeks. But the law also allows anyone — regardless of whether they live in Texas or have any association with the patient — to sue an abortion provider who violates the ban or anyone who helps a patient obtain an abortion. In the 10 months since SB 8 went into effect, over a dozen states have introduced or signaled their intent to introduce copycat legislation. In recent weeks, Idaho and Oklahoma passed laws that deputize private citizens to sue people who aid and abet abortion. Republican lawmakers have also signaled their desire to adopt model legislation from anti-abortion groups that would allow private citizens to sue anyone who helps a person access abortion care outside of their state of residence — a current necessity for people in many states.

The anti-abortion movement shaping our nation’s abortion laws have a clear goal: to create a terrifying and isolating environment for people seeking abortion care. Current laws and proposed legislation cut prospective abortion patients off from health care they need; practical support networks that offer information, guidance, and resources; and friends and loved ones. Abortion remains highly stigmatized. When you throw in the risk of criminalization, how many people can afford to take on the risk of driving someone to a clinic or across state lines to access abortion care if it means potentially facing a $10,000 lawsuit? How many small newsrooms can afford to take on the State if laws make it illegal to host or maintain a website “that encourages or facilitates efforts to obtain an illegal abortion”?

The anti-abortion movement knows that criminalizing pregnant people seeking abortion care would be a bad look for their movement, which purports to care deeply for women. But championing legislation that targets people who provide abortion support is part of a larger strategy to make people seeking abortion care feel desperate and alone. The anti-abortion movement — and the many lawmakers in their pockets — know that it’s easier to force someone to have a child with laws that incite fear and legitimize the surveillance and policing of trusted and established abortion support networks. The way we fight back is also the way we become targets: by educating people on the legal risks associated with self-managed abortion, and sharing information about abortion medication.

Increasingly, proposed anti-abortion legislation doesn’t just criminalize people who provide abortion support; it seeks to expand the definition of what it means to provide support

In the coming weeks, newsrooms should seriously assess the proposed legislation coming from anti-choice groups. It’s also time for journalists to push for conversations with newsroom leaders about the protections available to journalists who aid and abet abortion — otherwise known as providing accurate and timely information about abortion, a basic function of our jobs.

The dragnet of abortion criminalization will only expand further and further — largely because the people with the power to codify Roe into law and meaningfully combat abortion criminalization don’t seem particularly invested in doing either. It took President Joe Biden two weeks to substantially address the end of Roe in the form of an executive order aimed at protecting “reproductive health care services.” Democrats’ inaction — and the president’s toothless plan—do little to instill hope that the nation has the leadership it needs to navigate the rising tide of white Christian fascism that’s primed to swallow us all.

If you’re a journalist who assumed the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe would not affect your work, you haven’t been paying attention. The anti-choice movement’s decades-long fight was never just about abortion. As a movement deeply rooted in white supremacy, it was about social control through attacks on bodily autonomy. History shows us that to be successful, fascist projects require stifling the media, controlling the narrative, and limiting access to information. Increasingly, proposed anti-abortion legislation doesn’t just criminalize people who provide abortion support; it seeks to expand the definition of what it means to provide support. The road out of this mess is unclear, but one thing is certain: Unless serious action is taken, we should prepare to enter a new era of criminalization — and a very dark chapter in our nation’s history.

—

Tina Vasquez is a movement journalist with more than a decade of experience reporting on immigration, reproductive injustice, gender, food, labor, and culture. Currently, she is the editor-at-large at Prism, where she reports on immigration, reproductive injustice, and labor. She is a 2021 McGraw Center Fellow reporting on back wages owed to migrant farmworkers. Tina also serves on the board of Press On, a Southern journalism collective that strengthens and expands the practice of journalism in service of liberation. She is based in North Carolina.