Those Who Don't Exist

César Lepe looks at brain imaging done in August 2022, two years after his first COVID-19 infection. The PET-CT (full-body tomography) showed a decrease in metabolic activity in different areas of his brain. Jalisco, Mexico. December 6, 2022. Photo by Quetzalli Blanco

In Mexico, the government ignores long COVID, and health systems belittle long-haulers suffering neurological and neuropsychiatric aftereffects

Editor’s note: This story was produced with the support of the Pulitzer Center.

Haga clic aquí para leer el reportaje en español.

Until October 2020, when he became infected with COVID-19, César Lepe was a healthy 29-year-old public servant living in the state of Jalisco. Today, César, 32, is unemployed and completely dependent on his parents' care.

Two weeks after recovering from his infection, Lepe began to experience worrisome neurological and neuropsychiatric symptoms, including tremors, numbness, prickling sensations in his extremities, brain fog, and short-term memory loss.

“I’ve spent 24 months lying in bed experiencing a long list of symptoms that started with the COVID infection,” Lepe told the palabra team, who spent three days with him and his family at their home in western Mexico in December 2022.

Over time, Lepe has developed more symptoms, and his original symptoms have worsened. His bedroom is now his world. From there, he paints watercolors and manages the largest social media group for patients with long COVID in the country: COVID 19 Persistente México Comunidad Solidaria .

“César was my first long COVID case,” says Dr. Giorgio Franyuti, the former biosecurity coordinator of the Secretariat of National Defense during the first year of the pandemic. "He had already seen dozens of specialists and I had treated thousands (of COVID-19 patients), but I had not seen aftereffects beyond respiratory ones and those associated with barotrauma (lung damage in patients who needed a respirator)."

In Lepe’s case, his lymphocyte levels are similar to those of a person with HIV or lupus. A PET-CT (full-body tomography) scan revealed a decrease in his brain’s metabolic activity that was initially thought to be autoimmune encephalitis, though that was ruled out with further studies.

Lepe has visited dozens of doctors at public and private hospitals. His family has paid for dozens of exams, tests, and medical appointments — expenses that his private health insurance won’t reimburse unless he is diagnosed with something other than long COVID.

Mexico has multiple government-run health care systems, commonly referred to as social security, for people employed in the public and private sectors. Their purpose is to ensure access to free medical care for such people and their families, in addition to guaranteeing monetary income for pensioners and those on disability (due to work accident or illness).

While Lepe was still working and had social security, it took six months for him to be treated at the highly-specialized hospital of the Mexican Social Security Institute in his region, Centro Médico Nacional de Occidente. IMSS, the institute’s Spanish acronym, is the decentralized government body responsible for health services for around 50% of Mexicans. In April 2021, Lepe says, an immunologist told him, after listening to his medical history, that they had no treatment to offer him and that it was difficult to obtain dexamethasone to save intubated patients. (Shortages of essential and specialized medicines are a marked problem in Mexico.)

When vaccines arrived in Mexico, Lepe had doubts about whether or not to get vaccinated, he says. The health of some members in the Facebook group (COVID 19 Persistente Comunidad Solidaria México) deteriorated, while other members improved. In September 2021, the month after vaccines became available for his age bracket in his area, he got his first shot and his neurological symptoms worsened.

It angers Lepe that doctors have belittled and mistreated him. "They’ve called me names, told me to go to a psychiatric hospital, that I am ruining my parents' lives."

Efrén Lepe and Rosalía Medina, 32-year-old César Lepe’s parents, have tried multiple types of masks to minimize the risk of their son being reinfected with COVID-19. Despite the family’s efforts, César has been infected at least four times. Jalisco, Mexico. December 9, 2022. Photo by Quetzalli Blanco

Lepe was infected with COVID-19 for the fourth time in March 2023. He was admitted to a hospital for people without social security in the state of Jalisco as his health continued to decline. In May, he was finally diagnosed with hypogammaglobulinemia, secondary to long COVID, and began an intravenous immunoglobulin treatment commonly used in other countries for people with long COVID.

The birth of long COVID

Since the spring of 2020, people on social media around the world have been calling symptoms lasting more than 12 weeks after an initial infection “long COVID.” The range of symptoms is vast, and includes conditions and aftereffects beyond just pulmonary ones. Symptoms can be neurological, neuropsychiatric, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, autoimmune, endocrinological, renal, and dermatological as well.

In late 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) published the clinical definition of “post COVID-19 condition”: symptoms that last at least two months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis. Two of the three most common symptoms are neurological: fatigue and cognitive dysfunction.

The WHO also revealed a statistical review of 15 international studies on COVID long-haulers: 58% suffer from fatigue, 27% from attention deficit, and 16% from memory loss. “COVID-19 is not a respiratory virus. It spreads through the air, but it is a multisystem virus,” explains study co-author Carol Perelman.

Dr. Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, Rehabilitation Medicine chair at the University of Texas at San Antonio, explains that the best management for long COVID “is a multidisciplinary one that centers the patient. If the symptoms are neurological and neuropsychiatric, it’s advisable to see a physiatrist who, together with a neurologist, can coordinate treatment and medication to manage symptoms.”

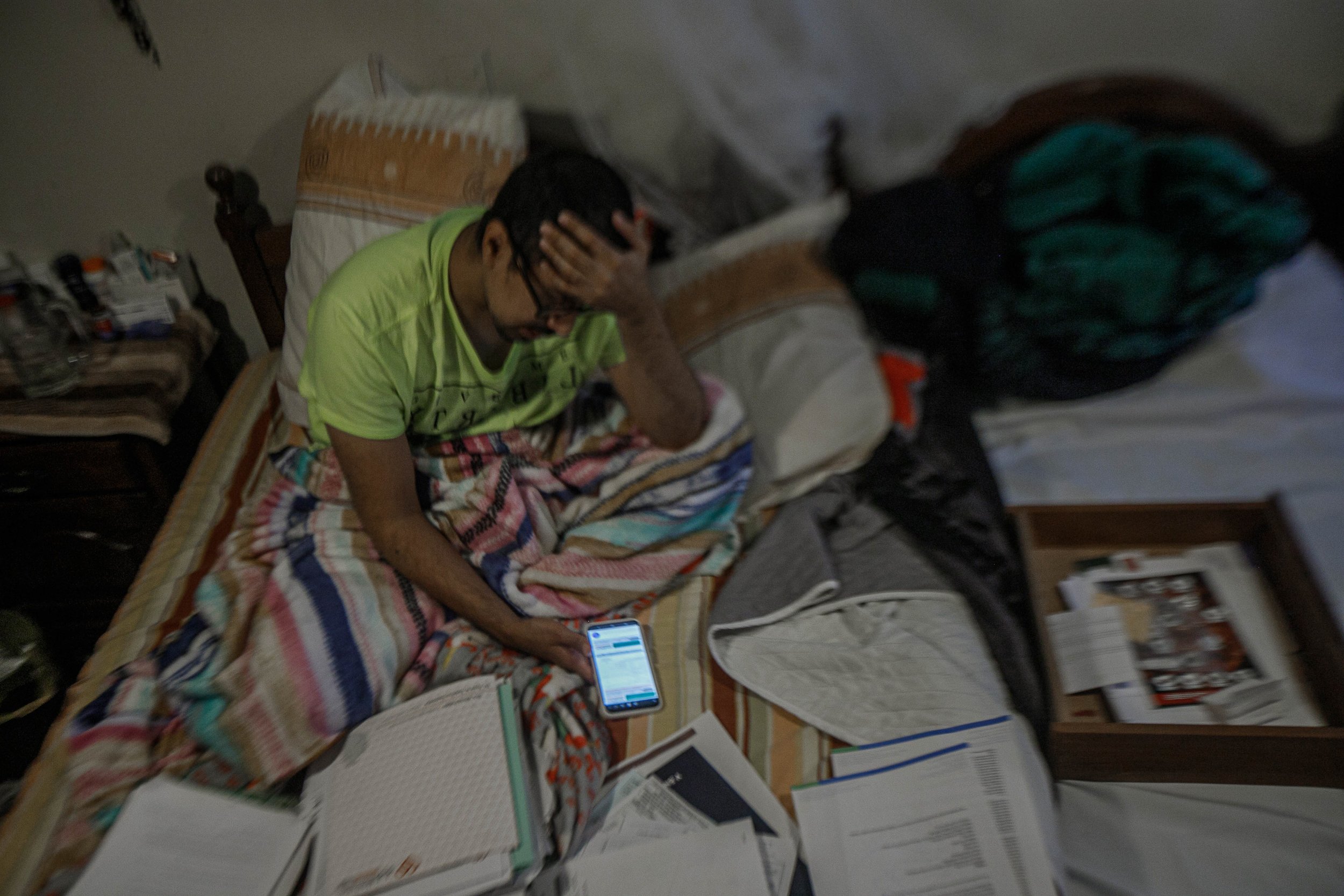

César Lepe, the founder of the largest social media group for COVID long-haulers in Mexico, supports other long-haulers while bedridden himself. The former civil servant has two university degrees: one in Urbanism and the Environment and the other in Genomic Biotechnology. Jalisco, Mexico. December 6, 2022. Photo by Quetzalli Blanco

Investigations in the United States, as reported by the Government Accountability Office, estimate that 10% to 30% of people who become infected with COVID-19 develop long COVID. Additionally, an analysis partially financed by the British government estimates that 33% to 62% of those infected with COVID-19 develop neurological and psychiatric aftereffects within six months of infection.

In the United States, the Census Bureau, in coordination with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), has been collecting statistical data on long COVID since April 2020. The CDC also developed guides about long COVID for healthcare providers and the general public.

Mexico’s northern neighbor has multiple care centers for people suffering from long COVID. Still, Verduzco-Gutierrez explains, it’s rare for COVID long-haulers to be able to access multidisciplinary care, unless they’re hospitalized in multispecialty hospitals, an unusual occurrence for people with long COVID. Some U.S. long-haulers say that these specialized long COVID clinics haven’t made an effort to create multidisciplinary teams, which forces long-haulers to research their medical conditions themselves to be able to access different specialists.

In Mexico, the federal government doesn’t include long COVID among diseases under epidemiological surveillance, nor has it created long COVID protocols. It also doesn’t count cases or disclose information to health personnel or the general population.

Hugo López-Gatell Ramírez, spokesperson and head of Mexico's pandemic response, declared on March 1, 2022, “the idea that there must be surveillance — a census or a specific registry — of a health condition that’s highly variable and multicausal really doesn’t have much useful technical foundation in public health.”

palabra interviewed five people with long COVID aged 29 to 40 who did not have previous health problems, are still suffering from neurological and neuropsychiatric conditions more than a year after being infected with COVID-19, and who have experienced a lack of appropriate care in public and private health systems.

Around 33 million Mexicans, the vast majority of whom are informal workers and their families, depend on free health services from the federal and state governments. These services often suffer scarcities, especially compared to other free services offered by the federal government through semipublic entities to people categorized as taxpayers.

Of the five people interviewed, two lost access to health services provided by institutions for salaried workers and students registered with social security. Since then, they’ve had to seek medical care in public hospitals specifically for people without social security.

Doctors insult and ignore COVID long-haulers

Mayra Mora, a 40-year-old clinical psychologist, has social security as a professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, in Mexico City. She’s affiliated with the Institute of Safety and Social Services for State Workers (ISSSTE), a semipublic entity responsible for providing health services to about 9% of the country's inhabitants, second only to the IMSS. Between them, the two institutes serve close to 60% of the country's population.

Mayra Mora has suffered neurological symptoms since she was infected with COVID-19 in August 2020. The Universidad Autónoma de México professor had to move to make getting around the city easier. Fatigue and intense pain prevent her from going long distances. Mexico City, Mexico. February 23, 2023. Photo by Quetzalli Blanco

In August 2020, following a two-week COVID infection, Mora began to experience severe joint pain, electric shocks in her muscles and fatigue. Two months later, she could no longer walk, go to the bathroom, or lift a spoon. Since there were no appointments available at ISSSTE, she went to three private specialists. The first two told her that her problems were psychiatric. The third, based on electrical activity of her muscles and nerves, diagnosed her with mixed demyelinating polyneuropathy ― a neurological disorder in which nerve swelling causes loss of strength or sensation ― due to the aftereffects of SARS-CoV-2.

In October 2020, Mora went to the ISSSTE with her results that showed polyneuropathy. Even with that information about her diagnosis in hand, the doctors she saw told her that there was nothing wrong with her and that COVID-19 did not cause symptoms like hers.

In 2021, Mora had to conduct classes and work appointments from bed. “I didn’t return to ISSSTE for a year. I could barely walk, the elevator in my clinic didn't work, and the last two times I left crying. They won't give me medication, they won't help me, they won't grant me disability.”

In January 2022, her ISSSTE family doctor authorized escalating Mora's case to the highest care level. After six months of waiting, the institute's specialist who saw her approved an MRI and a new test of electrical activity of her muscles and nerves (electromyography, or EMG). In November, the specialist informed her that her MRI was fine and that they saw improvement on her EMG. Mora insisted that she suffered severe muscle and joint pain, particularly pain in her left leg that made it difficult for her to walk. Mora says the specialist told her that she needed to see a psychiatrist and lose weight.

Nearly three years after her first COVID infection, Mora has been diagnosed by private doctors with polyneuropathy, fibromyalgia, insulin resistance and Raynaud's syndrome. She was also recently diagnosed with dysautonomia, a malfunction of the central autonomic nervous system which causes dizziness and rapid heart rate, among other debilitating symptoms. She suffers acute muscle and joint pain, numbness in her legs and palms, brain fog, and extreme fatigue. All of these symptoms are cited in the WHO’s definition of long COVID. Before, Mora had none of these ailments, and she hopes that ISSSTE will recognize her as a COVID long-hauler, treat her, and approve her disability. "If they don't name us, we don't exist."

Between 2021 and 2022, 31,148 people had long COVID care appointments at ISSSTE clinics and hospitals. In the same time period, at the national level, the institute only approved seven partial disability statuses and 17 total disability statuses due to "sequelae (aftereffects) of COVID-19."

Mayra Mora looks at photos from before her COVID-19 infection three years ago. She can’t leave home to hang out with her friends on the weekends without feeling exhausted the next day. Now, her family and friends visit her at home. Mexico City, Mexico. April 28, 2023. Photo by Quetzalli Blanco

Barriers to public services

The IMSS document “Comprehensive Care Protocols: COVID-19 Prevention, diagnosis and treatment" dedicates 12 of 153 pages to the rehabilitation of patients with a history of COVID-19: at the basic care level, doctors must identify COVID aftereffects, and if necessary, refer patients to rehabilitation units or to specialists at IMSS’ third level of care (for patients with complex diagnoses).

It was 8:30 a.m. and a 39-year-old long-hauler was waiting in front of the Long COVID Comprehensive Rehabilitation module of the IMSS Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Unit North, in Mexico City, where he agreed to an initial interview with palabra. (He was too exhausted and stressed to talk longer, and we did not get his name.)

“I don't know when I was infected. I realized something was going on in January 2022. I started to feel very tired; I got annoyed really easily. There are days that I can't even tolerate myself," says the man, whom we will call Antonio, on February 8, 2023.

Antonio was the only patient in the room, and that day he would receive his fourth and final session in the module, a rectangular room with six SciFit PRO1 upper body exercise machines.

An exceedingly small minority of patients get long COVID appointments at IMSS’ third care level. In 2020 and 2021, the institute recorded more than 97,297 appointments related to long COVID, but only 4.8% of these were in IMSS third care level hospitals (specialized care hospitals).

In response to public information access requests, the IMSS reports that three complementary medical units offer subsequent care to patients with long COVID issues. Between 2020 and 2022, the three units saw 1,635 patients for neurological aftereffects from COVID, an average of one patient per day. Of these patients, 96.2% were seen at the IMSS Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Unit North, where Antonio had his appointment in February 2023.

"I don't have reflexes in my legs, I don't feel them," Antonio says. He had been waiting since December 2022 to be treated in Neurology at an IMSS third care level hospital.

"Honestly, I'm already tired and especially from being in hospitals," he says upon saying goodbye, apologizing for not wanting to talk more about his experience. "Go here, go there, and right now what I'm trying to do is calm myself down a bit." We do not know if Antonio ended up being seen at the IMSS third level hospital.

If patients suffer neurological complications or aftereffects, the recommendation is rehabilitation and a neurology referral, the institute says. In 2020 and 2021, IMSS neurology services granted a total of 690 consultations for COVID-19 aftereffects, an average of less than one per day nationwide, according to data from the institute’s Department of Medical Resources.

palabra requested an interview with IMSS officials. The institute's Department of Medical Resources responded by email, saying that the IMSS Division of Clinical Excellence has developed 13 pages in official documents dedicated to care for patients with aftereffects from COVID.

Regarding the scant 690 Neurology consults for long COVID, the response stated that "an important number of patients with COVID-19 aftereffects surely received care in the Comprehensive Rehabilitation Services.”

Sedation instead of treatment

Mayra Domínguez, 29, was infected in June 2020, while in the last semester of her architecture studies in university. Today, she has a degree, but her dream of creating an interior design studio remains on hold while she suffers from neurological symptoms.

Early on, she lost mobility in her legs and feeling in her face and left arm. Her symptoms increased in the following months, including fatigue, sensations of electric shock in her head, involuntary movements, vertigo, and tachycardia (elevated heart rate).

César Lepe with his mother, Rosalía Medina. Rosalía is preparing a B-Complex injection for her son. César sleeps under a mosquito net to protect him from bites and potential dengue infection. Jalisco, Mexico. December 7, 2022. Photo by Quetzalli Blanco

One month after Domínguez contracted COVID-19, her white blood cells, as well as her inflammatory and coagulation markers, were elevated. At the end of that year, when she still had social security, a cranial tomography performed at the IMSS revealed a grade I cerebral edema (abnormal accumulation of fluid in the brain). IMSS discharged Domínguez without a diagnosis.

By 2021, Domínguez had to rely on family members to be able to eat, comb her hair, and bathe. The following year, her fatigue and tachycardia improved, but she began to have seizures. "(In the hospital) they say they’re motor seizures, but I feel as if my brain were inflamed," she says. “Pressure in my ears and pain in my head. I lose mobility in half my face. I babble. I lose all my strength on my left side and suddenly my brain shuts down. I become lethargic and can’t react, but I’m still conscious.”

“The only thing they’ve done when I have a seizure is sedate me or give me sleeping meds,” says Domínguez while at the Dr. Juan Graham Casasús Regional Hospital in the state of Tabasco. It was February 8, 2023, and Domínguez had been admitted to the hospital six days earlier, for the third time since 2020. In previous hospitalizations, she had been discharged with conflicting diagnoses: catatonia (a neuropsychiatric syndrome characterized by motor and behavioral abnormalities) and somatization syndrome (a disorder that causes extreme anxiety because of physical symptoms, even when other serious illnesses have been ruled out).

During her hospitalization in February 2023, a neurologist witnessed one of her seizures for the first time, says Domínguez. The MRI and lumbar puncture done didn’t provide answers about her condition. According to Domínguez, the specialist expressed that she was somatizing (that is, he doubted there was a physical explanation for her symptoms), as she heard him talking to a psychiatrist during the seizure. In her discharge note, hospital staff would attribute her seizures to possible psychiatric or psychological problems.

“Since yesterday, they’ve stopped coming in when I have a seizure,” says Domínguez.

Domínguez remained hospitalized for 15 days in Tabasco, her home state on the southern coast of the Gulf of Mexico. She recounts that she was given a benzodiazepine, an antidepressant, and a sleeping pill, as well as an antiepileptic and a glucocorticoid. All of these, except the sleeping pill, were mentioned in her discharge note, which also reads: “Noting (patient) resistance to ingestion (of the antiepileptic and glucocorticoid).”

Infographic by Tomás Benítez

“I feel that (the antiepileptic) increases the seizures, increases the electrical currents and tachycardia. It makes me euphoric; I can't stand it,” says Domínguez while hospitalized. She says that her doctor insisted that she had to take the medicine, even if it made her feel worse. Domínguez was discharged with a prescription for the same antiepileptic, as well as the antidepressant and benzodiazepine.

Domínguez was discharged with three new diagnoses: chronic fatigue syndrome, neuralgiform cranial syndrome (moderate to severe headache attacks), and mixed dissociative disorders (loss of total or partial awareness of one's own identity, immediate sensations, and control of movements).

“They never told me at the hospital that they had given me those three diagnoses,” Domínguez said in May 2023. “I suppose they realized that it wasn’t somatization. However, they never stopped treating me as if it was, which is why I was ignored." She adds that, despite the fact that her discharge note says "Open appointment in the emergency room," she was recently denied care there.

palabra requested an interview with Dr. Juan Graham Casasús Regional Hospital authorities about Mayra Domínguez's case, through the Tabasco state Health Secretariat. An interview was not granted.

"I can't even play with my kids"

Unlike César Lepe, Daniel Zamora first got vaccinated and then contracted the virus. In addition to long COVID, the WHO recognizes that some people suffer post-vaccination adverse effects.

During the months after his second vaccine dose in September 2021, Zamora, 31, went to the emergency room a dozen times. He was treated at Hospital Ángeles – a highly-specialized private hospital in the city of Puebla, in central Mexico – for symptoms that he describes as pre-heart attack.

"I felt as if there were electric shocks from my arms outward, like an electrical current, and as if my heart was racing too much," he says via video call. “The only tests they did were electrocardiograms and D-dimer tests and everything came out normal,” continues Zamora, a former sales manager at a call center company, who has private health insurance. A father of two children, he has been on disability since last year.

In February 2022, Zamora was infected with COVID-19 for the first time, with mild symptoms. But, three weeks later, he experienced chest tightness and passed out. He went to an internist, who diagnosed him with anxiety, as frequently happens to COVID long-haulers. A cardiologist performed an echocardiogram and an MRI of his heart, which revealed myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle) and pericardial effusion (excess fluid in the layer surrounding the heart).

Zamora spent three months in a wheelchair, between March and May 2022. "I couldn't even get up to go to the bathroom, the exhaustion was terrible," he says. His blood pressure rose and dropped constantly. Then, one day in June, he heard ringing in his ears, and at night “when I went to bed, it would come back, poom poom poom.” Two days later, while eating breakfast, his eyes closed involuntarily, he says, “as if I was falling asleep. I was trying to raise my head because I felt pressure, like a heavy helmet pushing down.”

Zamora attended appointments with four “of the best neurologists” at the hospital, he says, who ordered CT scans and X-rays but found nothing. The fifth neurologist referred him for a cranial MRI and diagnosed “severe long COVID inflammation.” The specialist prescribed steroids on which, for a short time, he improved slightly.

In the Lepe Medina household, both parents and their son take numerous kinds of vitamins to strengthen their immune systems. Jalisco, Mexico. December 7, 2022. Photo by Quetzalli Blanco

It was then that Zamora traveled to the Mexican capital to visit the prestigious private ABC Medical Center. They weren’t able to diagnose the origin of the inflammation, either. “The headaches were unbearable,” says Zamora. “They gave me drugs for relieving cancer pain.”

Back in Puebla, during the following months, Zamora says, he “still (felt) pressure, I couldn’t think clearly, like classic brain fog. I forget things a lot." In addition, he suffered joint and muscle pain. "I was carrying my daughter and, the next day, it was disastrous, as if I had done a bodybuilding exercise."

“It’s been very upsetting to hear that it’s anxiety and that the problem is psychiatric. It's not," says Zamora, referring to some doctors he’s seen. “These pains that those of us with long COVID have are savage. I’ve cried every day trying to find a solution; my wife has seen me. I can't even play with my kids."

Zamora says that most of the doctors he has consulted recognize that his symptoms are due to long COVID. However, his health insurance will only refund costs related to his pericardial effusion.

“It is not a specific disease that requires monitoring”

In January 2019, President Andrés Manuel López Obrador assured the country that, by the end of that year, his government would offer public health services comparable to those of Denmark, Canada, or the United Kingdom. Such services would be offered in IMSS and ISSSTE hospitals for those with social security. For those without social security, they would receive services through the then-newly-created Wellbeing Health Institute (INSABI in Spanish), which replaced the previous Seguro Popular, or Popular Insurance.

Three years after its creation, in May 2023, INSABI closed down. Free health services for people without social security are now the responsibility of a new entity: IMSS-Bienestar, a former IMSS program for people in marginalized areas.

Through public records requests, INSABI – now shuttered – informed palabra that it ran four hospitals. One of these hospitals recorded 769 appointments for long COVID between 2021 and 2022. IMSS-Bienestar, on the other hand, reported 105 hospital discharges in 2021 of patients whose main condition was long COVID.

“The only way to get a serious estimate of infection prevalence would be through a national probability sample,” said Dr. Jaime Sepúlveda Amor, executive director of the Institute for Global Health Sciences at UC San Francisco, in an email interview with palabra. Sepúlveda Amor spent two decades heading the top epidemiological and public health institutions in Mexico.

According to official National Institute of Public Health (INSP) estimates, at least 58% of the population (73 million Mexicans), had been infected with COVID-19 by late 2021.

Currently, the federal government reports 7.6 million confirmed COVID cases in Mexico, and just under 829,000 suspected cases.

“The estimates that INSP did in past years showed high prevalence,” added Sepúlveda Amor. “I would say that at least 80% of the Mexican population has been infected — symptomatically or asymptomatically — with SARS-CoV-2.”

The WHO estimates that 10% to 20% of those who get SARS-CoV-2 develop long COVID. In other words, using the INSP’s statistic of 58%, 7.3 million to 14.6 million people have developed long COVID-19 in Mexico, if not more.

"Everyone has the option to be treated if they have one, two or 30 of the symptoms accompanying long COVID," said the federal Undersecretary for Prevention and Health Promotion, Hugo López-Gatell Ramírez, at a press conference on March 1, 2022. "The National Institutes of Health have been helping in establishing more or less standardized clinical care protocols, according to the situation, in order to more efficiently care for these people."

Mayra Mora has had numerous studies and tests done since she was infected with COVID-19. She has been diagnosed with five other conditions since 2020. She is waiting for a long COVID diagnosis. Mexico City, Mexico. April 28, 2023. Photo by Quetzalli Blanco

At that press conference, López-Gatell thanked the National Institute of Medical Sciences and Nutrition and the National Institute of Respiratory Diseases for promoting working groups of clinical specialists to establish such protocols. One year after the declaration, however, through responses to public records requests, the aforementioned institutes said there were no projects for the creation of long COVID care protocols in existence.

In Mexico, clinical research is financed by pharmaceutical companies, points out Dr. Samuel Ponce de León, head of the University Commission for Coronavirus Emergency Care at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. For example, he explains, trying to identify the frequency of long COVID neurological symptoms would require multiple MRIs for x number of patients, plus clinical studies, personnel, and facilities. For each participant, the investment could amount to $50,000. “They will never authorize it; to begin with, there are no funds,” says Ponce de León.

In the aforementioned press conference in March 2022, government epidemiologist López-Gatell also declared: “There was a proposal to add long COVID to the list of diseases subject to epidemiological surveillance in Mexico. From a medical point of view, it makes no sense because it is not a specific disease that requires monitoring as such.”

In Mexico, there are 170 diseases subject to epidemiological surveillance. Including long COVID would be intimidating for the authorities, explains Franyuti, the former biosecurity coordinator for the Ministry of National Defense. “If they were to start monitoring it (long COVID),” he continues, “numbers would shoot up dramatically… It would be almost the size of diabetes.” The next step, he says, would be to "train and empower primary care physicians so that they can diagnose it."

In the United States, in the summer of 2021, the Biden administration declared long COVID a potentially disabling health condition under the Americans with Disabilities Act. A 2022 report by a non-governmental research organization, Brookings Institution, estimated that 2 million to 4 million Americans were unable to work because of the condition.

In Mexico, public dissemination by federal health authorities about long COVID is limited to a single social media post from December 19, 2022. "Between 31% and 69% of COVID-19 survivors," it states, “can develop long COVID.” On the IMSS website, the institute has published 13 infographics on topics including “walking” and “anxiety,” among others.

'No decision maker has had to go to a public hospital, get up at 5 in the morning, and line up at 6 to be treated at noon.'

Notwithstanding López-Gatell's statements, as of 2021, by instruction of the Ministry of Health, diagnoses, causes of death, and medical procedures must be registered with the long COVID-19 codes of the WHO International Classifier of Diseases: U08 “Personal history of COVID-19,” U09 “Post COVID-19 condition,” and U10 “Multisystem inflammatory syndrome associated with COVID-19.”

palabra made requests to the federal and state governments for statistics for long COVID care registered with these WHO codes. According to the data provided by these entities, less than 150,000 people in all of Mexico have received any type of care for long COVID.

For his part, Franyuti points out that it’s contradictory to order the use of the WHO’s codes for long COVID-19 and, at the same time, not quantify cases. “It’s data that’s going to go straight in the trash.”

Iván Regalado, Mayra Mora’s partner, has taken on tasks that they used to do together, including cooking, cleaning the house, and walking their dog. The couple’s daily life changed once she was infected with COVID-19. Mexico City, Mexico. April 23, 2023. Photo by Quetzalli Blanco

Iván Regalado, Mayra Mora's partner, wishes the country's doctors had more empathy. “This disease, which is new and requires more research, is difficult to treat,” he says. Doctors must “accept that (COVID long-haulers) have an ailment…that their illness is real. And start from there to rule out other causes.” He asks decision makers to visit COVID long-haulers so that they "see their ailments, their needs, and make their decisions based on that and not based on budgets."

palabra requested interviews with the Health Secretariat and ISSSTE but did not receive any responses.

"No decision maker has had to go to a public hospital, get up at 5 in the morning, and line up from 6 to be treated at noon," says César Lepe. “To be later given a prescription and go to the pharmacy, but they don't have the medicine. If you ever put them in such a vulnerable situation...overnight this would become Denmark".

—

Alice Pipitone is a freelance investigative journalist in Mexico, where she has collaborated with various print, digital and radio outlets. In Washington, D.C., she contributed to Newsweek en Español. And, in Colombia, she worked with the economic magazine Dinero’s investigative unit.

Quetzalli Blanco is a freelance photographer and visual journalist working in Mexico. Alongside psychology, she specializes in issues related to the victimization and re-traumatization of people in vulnerable situations, mainly women, children and the transgender community. Her research projects come from decolonial and humanist perspectives. Her photographs have been published in agencies such as AFP, Xinhua and Notimex.

Lygia Navarro is an award-winning disabled journalist working in narrative audio and print. She has reported from across Latin America, as well as on Latine stories in the United States and Europe. Lygia has reported for The American Prospect, Business Insider, Marketplace, The World, Latino USA, Virginia Quarterly Review, Christian Science Monitor, The Associated Press, and Afar, among other outlets. She has also worked as a podcast producer, and her work has been supported by many grants and fellowships, including, most recently, the Journalism & Women Symposium.