‘What if one day you leave and don’t come back?’

Concepción Ortíz inside her family’s home in Chicago on February 13, 2025. Concepción has lived in the United States for over 20 years with her husband. Lately, her fears have deepened as Trump seeks to deport millions. Photo by Sebastián Hidalgo for palabra/MindSite News

Many immigrant children in Chicago are too anxious to go to school, fearing parents will be deported.

Editor’s Note: Silent Battles is a reporting project focusing on the mental health of immigrant, refugee and asylum communities in the U.S. We begin in Chicago, a city founded by a Haitian immigrant that has the fourth-largest immigrant population in the country. The series is a collaboration between the Chicago bureau of MindSite News and palabra, a multimedia platform from the National Association of Hispanic Journalists. It is made possible with funding from the Field Foundation of Illinois.

Haz clic aquí para leer este reportaje en español.

A framed print of La Virgen de Guadalupe and a wooden crucifix stood out against the wall in Concepción Ortíz’s living room in the Southwest Side of Chicago. A television played cartoons for her 2-year-old granddaughter. Seated around the kitchen table, she and I talked as she served café con leche and seamlessly juggled the rhythms of her daily life.

“Everything has been about working, working,” Ortíz told me “We came to give our children a better life. With all that’s happening, I am afraid.”

Ortíz and her husband are immigrants living in the U.S. without documents. She has lived in Chicago for 20 years and her husband for nearly 30. Their youngest daughter, Guadalupe, is 14 and is a U.S. citizen. Guadalupe struggles with anxiety, a condition that has shaped much of her young life. (MindSite News and palabra are changing the names of family members to protect their identity.)

But lately, Guadalupe’s fears have only deepened since U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids have been targeting immigrant communities in Chicago, particularly in neighborhoods with large undocumented populations, as part of federal efforts to detain and deport people without legal status.

“She used to go to school, even though it was hard for her,” Ortíz said. “But now, she doesn’t want to leave the house at all. She’s scared something will happen while she’s gone, that I won’t be here when she gets back.”

Ortíz drew a flower on a piece of scrap paper, hoping to calm her granddaughter who demanded attention. When that failed, she handed her a lollipop.

Guadalupe was diagnosed with anxiety at the age of 10. She was prescribed medication and therapy, and for a time, it seemed like her condition was improving, according to Ortíz. But then, news of terrifying immigration raids in Chicago spread.

Since then, Guadalupe has refused to attend school. Some days, she doesn’t even leave her room. “She sleeps a lot. She just wants to shut everything out,” her mother said.

Ortíz has tried everything to encourage her daughter. “I tell her, ‘If you go to school for a whole week, I’ll take you out to eat’ — offering her favorite place, Raising Cane’s. Guadalupe regressed when one day she saw a girl in her eighth grade class crying because she heard ICE was near the school.

“She was afraid her mom wouldn’t be home when she got back,” Ortíz said. “She asked me, ‘What if they take you while I’m in class? Who will pick me up? Where will I go?’”

Ortíz spoke softly to avoid disturbing Guadalupe, who was in her room during our conversation. “Right now, she’s probably still asleep,” Ortíz said, glancing toward her bedroom. “She hasn’t eaten, but she took her medication. Maybe by noon she’ll come out.”

A painting of La Virgen de Guadalupe hangs next to family photos and a small altar in Concepción Ortíz’s home in Chicago. Photo by Sebastián Hidalgo for palabra/MindSite News

Trailed by unmarked cars

Chicago has been preparing for immigration raids for months, ever since Donald Trump’s election victory and his pledge to carry out “mass deportations” upon taking office. Even before his inauguration, reports suggested that the city would be among the first to be targeted. Advocates are prepared and have been offering advice and workshops on legal rights for schools and families.

Ortíz does not currently have a safety plan. “Right now, we haven’t made a plan because you don’t want to accept it, but I don’t know,” she said. “It would probably be good to make a plan, but sometimes you just don’t want to accept it yourself.”

Ana Guajardo, a community leader and co-founder of Centro de Trabajadores Unidos, an organization on the city’s Southeast Side that advocates for the rights of immigrant workers, said that they are “seeing families shut themselves inside their homes. Children are afraid to go to school. This is exactly what they want — to create fear.”

While official numbers on detentions remain unclear, fear has been enough to disrupt daily life for many residents without legal status. “There are unmarked vehicles following people for miles, then suddenly pulling off,” Guajardo said. “It’s clear they’re checking something — maybe scanning faces, maybe running plates — we don’t know, but we do know this is harassment.”

‘She hears things. And she asks me, ‘What if one day you leave and don’t come back?’’

Ortíz’s older children have families of their own and she worries that if she is deported, their work commitments will prevent them from meeting their younger sister’s needs. These include driving her to therapy, ensuring she takes her medication and making sure she attends school. As her daughter’s primary caretaker, Ortíz shoulders these responsibilities.

Her husband is the family’s sole provider. He works in the produce section of a local supermarket and drives his wife to stores and Guadalupe to therapy. The three share a rented apartment. “We can’t afford to miss even a single day of work, Ortíz said. “If my husband doesn’t go, we will fall behind on rent.”

Ortíz avoids talking about ICE raids with Guadalupe to keep her daughter’s anxiety from getting worse. “I try not to talk to her too much about it because I know it will make her even more anxious,” she said. “But she knows. She hears things. And she asks me, ‘What if one day you leave and don’t come back?’”

Concepción Ortíz and her granddaughter at home in Chicago. Ortíz tries to stay indoors in the wake of rumors of ICE activity near her community. Photo by Sebastián Hidalgo for palabra/MindSite News

Two weeks before I visited Concepción, reports surfaced that ICE agents had been spotted outside Hamline Elementary School, which has a 92% Latino student population.

The incident caused widespread fear and confusion due to initial reports suggesting that ICE agents had attempted to enter the school. It was later clarified that the individuals were U.S. Secret Service agents. School officials initially believed they were ICE agents, and per Chicago Public Schools (CPS) policy, denied them entry.

Since Trump’s inauguration, absenteeism has surged in Chicago Public Schools, according to Linda Perales, a Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) organizer who cited anecdotal reports from teachers at various CPS schools. Some reported attendance drops as low as 50%.

“We’ve been collecting information from our members — teachers telling us, ‘Half my students didn’t show up,’” Perales said. “Anecdotally, we’ve heard of one school where 1,000 students were absent in a single day. Another school reported just 53% attendance. Some teachers have said, ‘Half of my students have been out almost every day since the inauguration.’”

Immigration “walk-ins” rather than “walk-outs”

As an organizer with CTU, Perales leads sanctuary school and bilingual education efforts. She also helps lead the Latinx Caucus and the bilingual committee, working closely with educators in the neighborhoods of Pilsen and Little Village.

Perales mentioned that just a few hours before our meeting, she had visited Hamline Elementary to help coordinate a “walk-in.” She described walk-ins as acts of solidarity, during which teachers, parents, and students gather outside schools before the day begins to advocate for issues affecting their communities. This particular walk-in aimed to reassure students and teachers, offering a sense of support and safety amid growing fears of ICE raids in their neighborhoods.

Teachers and parents gather outside Hamline Elementary School during a “walk-in,” an act of solidarity to reassure students amid fears of ICE raids in the neighborhood. Photo courtesy of Linda Perales

Outside the school, teachers set up a table with pastries and coffee and held up signs that read: “Sanctuary for All” and “Los inmigrantes son bienvenidos aquí,” while distributing “Know Your Rights” cards and flyers to families as they arrived. A Bluetooth speaker played music as educators engaged with parents and students, emphasizing that the school was a safe space.

Perales said the walk-ins are part of a larger movement to expand the definition of “sanctuary,” ensuring protection for all students: immigrant, Black, LGBTQ and bilingual students while reinforcing teachers’ contractual rights to advocate for their students. The walk-ins also took place at multiple schools.

Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson, who is leading a “Know Your Rights” campaign for immigrants in partnership with the Chicago Transit Authority, has declared that Chicago will remain a sanctuary city. Trump announced on February 6 that he was suing Chicago, Cook county, and the state of Illinois for allegedly obstructing ICE raids.

“Instead of working with us to support law enforcement, the Trump Administration is making it more difficult to protect the public, just like it did when Trump pardoned the convicted January 6 violent criminals,” Illinois Governor JB Pritzker said in a statement. “We look forward to seeing them in court.”

In Chicago, the fight for sanctuary schools was led by CTU, particularly its Latinx Caucus, which had been organizing “Know Your Rights” workshops and solidarity actions since Trump’s first term. In 2019, CTU successfully bargained to include sanctuary protections in its contract with CPS, making it one of the first contracts in Illinois to explicitly protect immigrant students and educators. However, implementation has been slow, according to Perales, with CPS yet to roll out promised training on how schools should respond if ICE arrives.

“One big hurdle that we’re encountering right now is that CPS and CTU were supposed to collaborate to create training for members on how to respond if ICE shows up to the buildings,” Perales said. “It’s been in the contract since 2019.”

Currently, she explained, CPS places most of the responsibility for handling such incidents on school principals, which is an overwhelming burden. Perales believes that a broader team approach involving staff members and collaboration with community organizations and rapid response teams is necessary to ensure schools are better prepared.

“It does worry me,” Perales said. “What impact is it having on their mental health? What impact is it having on their ability to concentrate in the classroom? Are they worried that they're going to leave school and their parents are not going to be at home because they were detained?”

What’s also frightening, she said, is that Trump has deputized other federal agencies to act as immigration enforcement, blurring the lines between traditional law enforcement and immigration raids.

Activist Lapis Marigold with Revcom Corps Chicago talks to people outside of Hamline Elementary School after federal agents were turned away on January 24, 2025, in Chicago. Photo by Erin Hooley/AP Photo

A child’s question:“What have we done wrong?”

Schools have become important spaces where children talk to one another and learn about immigration enforcement, ICE raids, and their rights.

Some local schools have asked Guajardo and her team at Centro de Trabajadores Unidos to provide “Know Your Rights” workshops and guidance for parents. She said that students, many of whom are bilingual children of immigrant parents, are also sharing information among themselves.

For instance, before the election, one of Guajardo’s daughters learned from some friends that if Trump won, their families would have to make the choice to leave Chicago. Those friends have since stopped attending school, as their families have chosen to stay in hiding.

Children are not just absorbing information, they are actively supporting and educating one another in the face of uncertainty.

Another one of her daughters asked her if she could take “Know Your Rights” materials for school friends who expressed fear about ICE raids and if she could give them her mother’s information. Guajardo responded to her daughter saying yes, to let the families feel free to call her. “Kids are helping each other, oh my gosh!” she said, her voice filled with urgency.

According to local advocates, ICE agents have been conducting aggressive and possibly unlawful raids.

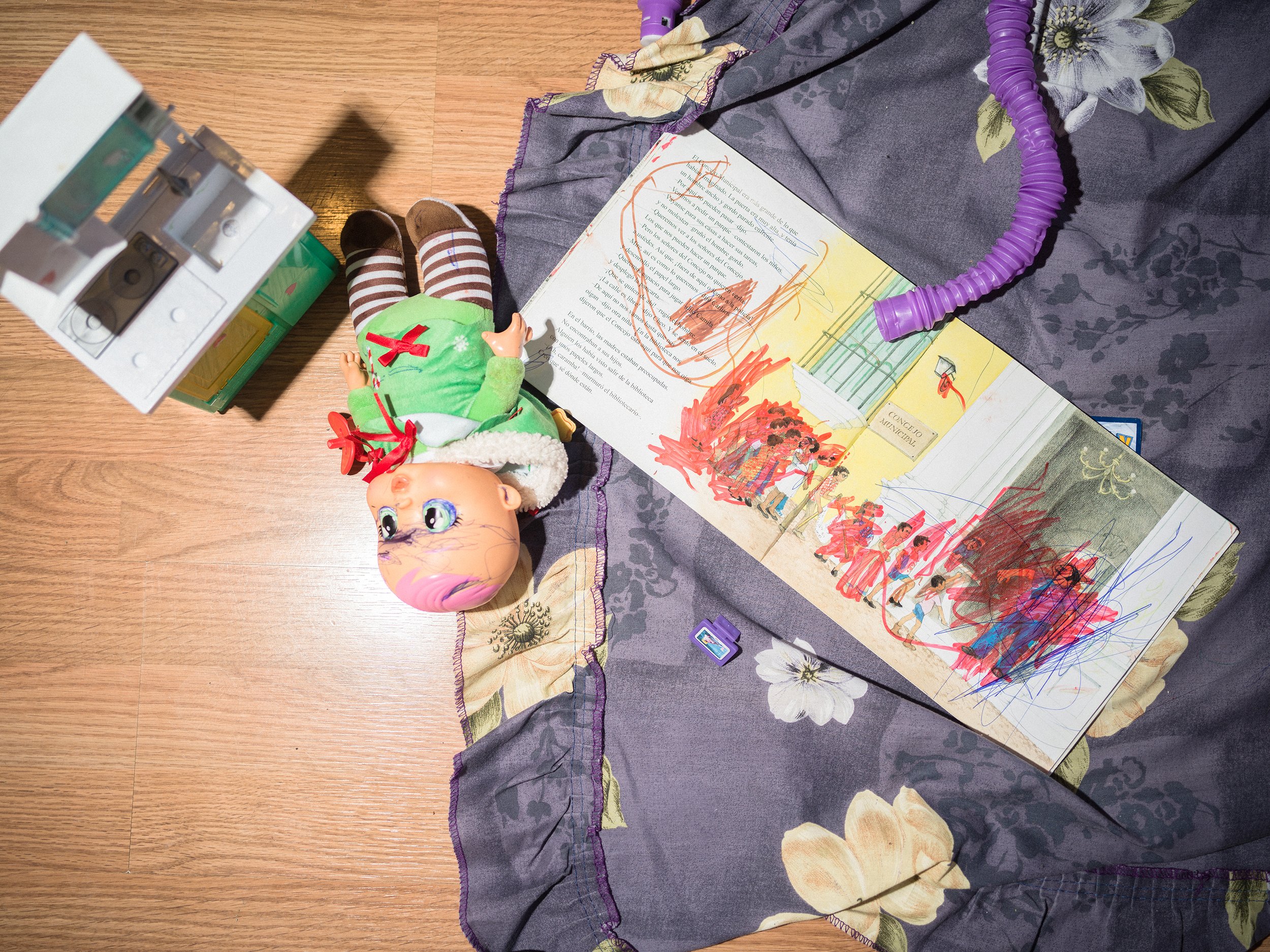

A children’s book and toys are marked with scribbles made by Concepción Ortíz’s granddaughter. Photo by Sebastián Hidalgo for palabra/MindSite News

Children and teens such as Guadalupe, who had been making progress with anxiety or depression, may now experience setbacks, their symptoms intensifying as they internalize fear and uncertainty.

“Generally, if you have a child who has a pre-existing mood or anxiety disorder, and you layer on top of that an acute or chronic stressor, that’s just going to exacerbate symptoms,” said Rebecca Ford-Paz, a clinical child psychologist at Lurie Children’s Hospital in Chicago who specializes in immigrant and refugee mental health. “A low-level depression might evolve into suicidal thoughts, or anxiety might become more prevalent and show up in panic reactions, sort of a hyper-vigilance.”

Support the voices of independent journalists.

|

Ford-Paz explained that children and teens experiencing immigration-related stress often exhibit heightened anxiety, difficulty concentrating, and academic decline. She said many become irritable, on edge, or struggle with sleep and separation from their parents. Confusion and self-doubt are common, as children internalize anti-immigrant rhetoric and question why their families are being targeted.

“Many talk about just feeling confused, like, ‘What have we done wrong? Why are people calling immigrants criminals? Why would they target our family?’” Ford-Paz said. “One of the tips we share with families is to reinforce that their feelings are valid, that they are not alone in feeling this way.”

“Children crave a sense of safety,” she added. “We encourage parents to reassure them, saying, ‘I am doing everything possible to keep you safe.’ We also help families create family preparedness or emergency plans — because in the absence of information, children will go to the most catastrophic scenario in their mind.”

But she also advised against making promises that cannot be kept. Rather than offering absolute reassurances like “Everything is going to be alright” or “Nothing bad is going to happen to our family,” she suggested that parents focus on affirming what they can control, using phrases like “you are safe now, and I am a safe person, and I’m doing everything I can to protect you.” She said that while certainty cannot be guaranteed, parents can tell their children that they will continue to share information and take steps to ensure their well-being.

Support for FamiliesFor immigrant, refugee, and asylum-seeking families, fears of separation, legal uncertainty, and limited access to resources can take a heavy emotional toll. However, support is available:

|

Ford-Paz also has another piece of advice for parents, as well as children: “Take breaks from the radio, the TV, and social media. There’s a lot of misinformation and fear-mongering that is perpetuated on social media.”

She pointed to a disturbing link between anti-immigrant rhetoric and bullying in schools. “There’s been an uptick in bullying, and certainly bullying has detrimental impacts on the mental health of children. Many of these children may internalize some of the anti-immigrant rhetoric, which can lead to self-deprecating thoughts, depression, and anxiety.”

Bullies often target immigrant children with insults and threats related to their appearance and immigration status, she explained. “Mostly, kids report things like being told they’re ugly because of the color of their skin or their hair, or that they’re going to get deported,” she said. “That’s the most common one — being taunted that they’re going to get deported, or that their family is going to get deported.”

Ford-Paz urges parents to provide children with empowering counter-narratives to build their self-esteem and resilience against negative messaging. The clinician emphasized that a key way to combat bullying is by fostering a strong sense of cultural pride and reinforcing positive identity in children. She highlighted the importance of storytelling, sharing cultural narratives, and teaching children about historical figures and activists who have defended immigrant rights.

Concepción Ortíz worries about her daughter’s mental health and her family’s future as Chicago has become a focal point for ICE immigration enforcement. Photo by Sebastián Hidalgo for palabra/MindSite News

In the midst of it all, Ortíz is grateful for the resources her family has found in Chicago — especially mental health support. “The therapist is seeing us both now. One session for me, one for Guadalupe.”

Ortíz is deeply concerned about how deportation would disrupt her daughter's access to crucial therapy. Her fear is two-fold: She worries about her daughter’s mental health and her future, but she also carries the weight of her own uncertainty.

“I don’t leave the house unless I have to. If I go out for groceries, I wait until my husband can take me,” she said. “Because what if I don’t come back? I think I might have anxiety too, but I’m just now realizing it.”

For now, Ortíz and Guadalupe take things one day at a time. Some days are better than others and Guadalupe talks about the future. Other days, she retreats into herself, disappearing into her room for hours. But Concepción refuses to give up. Every morning, she knocks on Guadalupe’s door, reminding her it’s time for school. Some days, the door stays shut. Other days, Guadalupe opens it.

—

Alma Campos is an award-winning bilingual journalist in Chicago. Born in Mexico, her path led her from Azusa, California, to Chicago’s South Side. Her work dives into the immigrant experience, capturing stories across a range of topics from mental health and labor to community resilience. She contributes to The Guardian, is a senior editor at South Side Weekly, and leads reporting on the intersection of immigration and mental health for the Chicago bureau of MindSite News. @alma_campos

Sebastián Hidalgo is a photojournalist and investigative reporter in Chicago who covers the intersection of low-wage labor and policing. @sebastianhidalgo_photo

Rob Waters is an award-winning health and mental health journalist and the founding editor of MindSite News. He has worked as a staff reporter or editor at Bloomberg News, Time Inc. Health and the Psychotherapy Networker and was a contributing writer to Health Affairs. His articles have also appeared in the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, Kaiser Health News, STAT, the Atlantic.com, Mother Jones and many other outlets. @robwaters001