The Power of Latino Radio

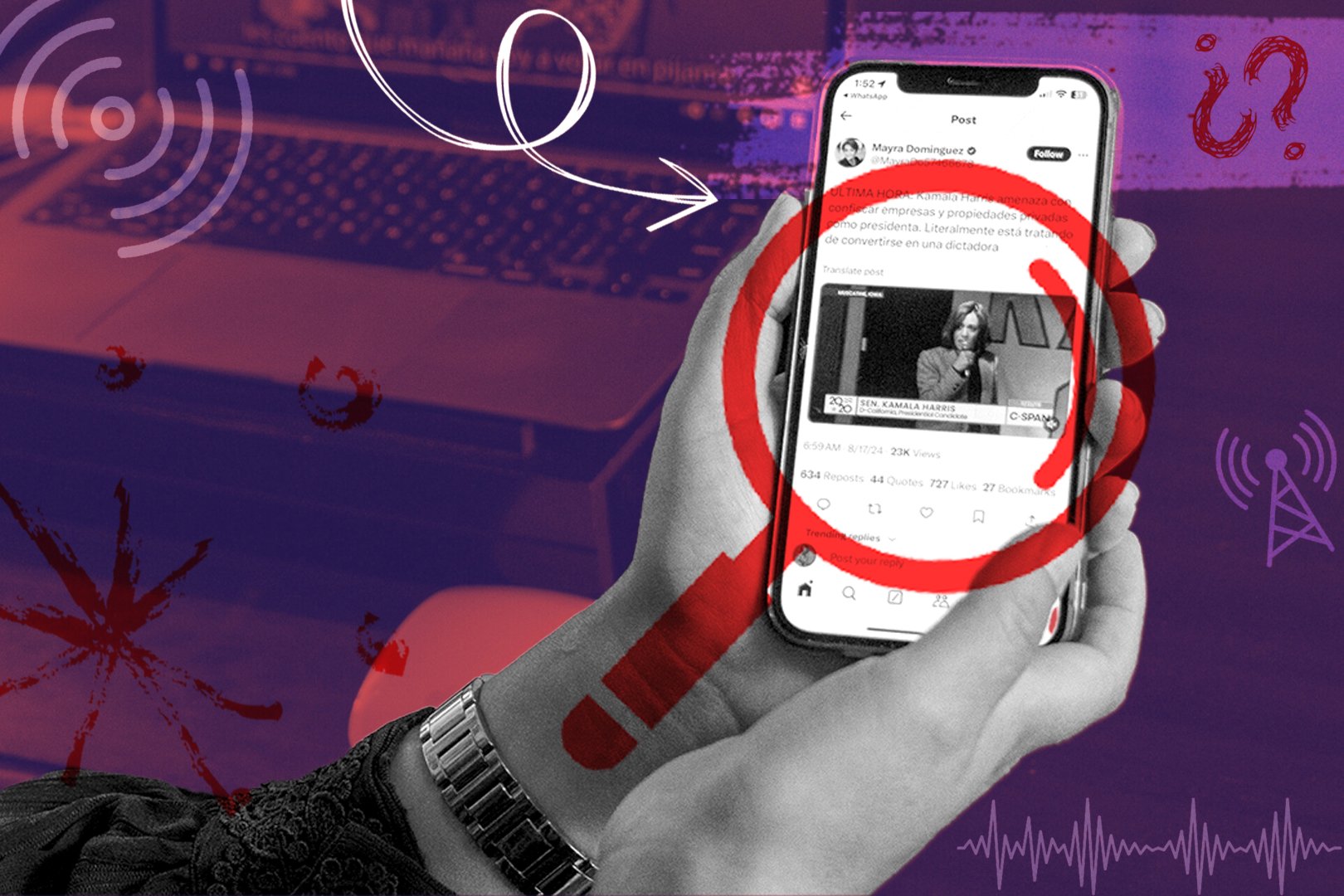

Photo by Jennifer A. Ortiz for Feet in 2 Worlds. Photo collage by Yunuen Bonaparte/palabra

Radio is a powerful tool of communication within Latino communities — but one that needs more oversight and accountability.

Editor’s note: This story is part of Frequency of Deception / Radiofrecuencia de engaños, a six-part series by Feet in 2 Worlds in partnership with WNYC’s Notes from America, palabra, and Puente News Collaborative on the spread of dis- and misinformation on Spanish radio in the U.S.

This radio piece was produced by Feet in 2 Worlds in collaboration with WNYC’s Notes from America.

Haz clic aquí para leer este reportaje en español.

Henry Siciliano scans multiple computer monitors in a chilly, air-conditioned studio at La Campesina 96.7 FM in Las Vegas. “El Lobo (The Wolf) Siciliano,” as he is known on the air, was until recently the host of the station’s midday show. The screens show ads for the day, news bulletins and music playlists.

“I want people, when they’re at their job, to feel like I’m chatting with them…” Siciliano said, “...like I’m sitting right next to them.” When he goes on the mic, he pictures talking to office workers at casinos downtown who tune in from their cubicles, or street vendors who work outside in the sun. He said that kind of companionship “has been the idea of radio for a long time.”

Radio Campesina, which broadcasts in Spanish, is a trusted messenger in the Latino community in the Southwest. It was founded by labor leader César Chávez in the 1980s and is run by the nonprofit Chavez Radio Group. The programming across Radio Campesina’s six stations usually airs from headquarters in Phoenix, but Siciliano’s local show in Las Vegas was an exception. Hosts like Siciliano have immense power to influence Latinos’ opinions on a range of subjects.

Henry Siciliano, better known as “El Lobo (The Wolf) Siciliano” by his former listeners at La Campesina 96.7 FM in Las Vegas. Photo courtesy of Henry Siciliano

Radio is an especially popular medium among Spanish-speaking Latinos in the U.S., reaching 94% of Hispanic adults. There are twice as many Hispanic radio stations in the country as there are National Public Radio network affiliates. For people who can’t afford daily newspapers or cable subscriptions, or for those who work long hours without access to their phones, radio is an indispensable source of news and entertainment. In addition, listening to the radio is a habit that many Latino immigrants in the U.S. bring with them from their home countries. But community organizers, media watchers, journalists, and others are sounding the alarm about the growth of inaccurate and deliberately misleading information airing on Spanish-language radio.

The November election has heightened the concern. Latinos are the second fastest-growing group of voting-age Americans. Over 36 million Latinos will be eligible to vote in November. In some states, including Nevada and Florida, more than one-fifth of the electorate is Latino. Latinos could be casting the deciding votes in places where the margins are narrow between parties or on issues. The fear is that many Latinos will make their choices on Election Day based on incorrect information.

Radio is an important part of a complex information ecosystem in Latino communities that also includes social media and friend and family networks. Because radio reaches such a wide audience, it can easily amplify misinformation and disinformation. Live radio is also difficult to monitor, and so the day-to-day task of ensuring that Spanish-speaking Latinos receive accurate information most often lies with individual radio show hosts and a station’s programming decisions. While there are plenty of trustworthy, reputable Spanish-language stations, the guardrails against misinformation and disinformation are largely set and upheld by the stations themselves.

Siciliano is hyper-aware of how misinformation can spread on the radio. He has worked in radio for 26 years at stations across El Salvador and the U.S. He first fell in love with the medium when he walked into a radio booth when he was around 11 years old. He takes his role as a communicator seriously. He checks news alerts on his phone, and glances at social media and online news sites to see what’s trending, making sure to always look at multiple sources. He’ll never forget the time he said on the air that a basketball player had died in Las Vegas, only to have a relative contact him to say that wasn’t true.

Information can be distorted in many ways, he explained, like playing a game of telephone. Or a host might exaggerate for entertainment value. “I knew a sports commentator. The ball could be on the other side of the field, but when he’d announce it, he’d make you think it was right in front of the goal and that they were about to score!” He laughed. “That’s what sells, but I never thought it was necessary for me to resort to that.”

‘You can have all the opinions you want in your heart. Nobody will try to change those. But it’s one thing to have an opinion based on a lie. And another to have an opinion based on a set of facts.’

Radio Campesina, a commercial radio station, also relies on robust programming and ad sales teams to avoid airing misleading advertising and to ensure that they broadcast useful information. “We just want to make sure that it's accurate, and that it's not misleading to our listening audience,” said station manager Rene Morales.

Spanish-language radio in Las Vegas is a competitive market. According to Morales, who also manages Radio Campesina’s stations in Phoenix and Yuma, Arizona, Latino listeners in Las Vegas account for 30% of the total market. The station’s listeners are Spanish-dominant — more proficient in Spanish than in English — and up to 85% of them are Mexican or Mexican-American.

Latino immigrants are much more likely than U.S.-born Latinos to get news from Hispanic outlets, or media sources that specifically target Latino consumers. “What I love about (the job) is that I'm in a position to be able to provide the information that I think is important to them,” said Morales, who himself comes from a family of Mexican immigrants.

Morales and his team are cautious with the information their stations air. The station provides an extra layer of scrutiny on top of what they are legally required to do. Under the Communications Act of 1934, commercial stations must provide opposing candidates in an election an equal opportunity to access their airwaves, and the Federal Communications Commission requires that broadcasters identify sponsored content on the air.

Morales’s approach faced a test in the 2022 midterm elections, when Radio Campesina declined to air a political ad that they determined was misleading. “The commercial was making some claims that certain medications were being given to children to change their sex,” Morales explained.

The anti-transgender ad did air on other Spanish-language radio stations as part of a campaign in Spanish and English by a conservative group called America First Legal that also included mailers and TV ads. The Colorado Sun and The New York Times reported that the ads targeted voters in Arizona, Colorado, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Tennessee and Texas. The director of strategic initiatives for the Human Rights Campaign, an advocacy organization focused on LGBTQ+ rights, told The New York Times that the ads aimed to make Latino and Black voters — who historically favor Democratic candidates over Republicans — “so fed up” that they stayed home that election.

Morales said they don’t often get such “off the wall messages,” but the sales, programming, and legal teams at Campesina decided not to run it.

Not all stations have the resources or the internal guidelines that allowed Campesina to avoid airing incorrect information. In Florida, in 2021, over a hundred Latino civil society leaders and residents sounded the alarm that Spanish-language radio was airing disinformation to thousands of listeners. They called for greater accountability at stations, which prompted an effort to gather concrete evidence to support their observations. South Florida is home to a large number of Spanish-language radio outlets, including over a dozen stations and several networks that broadcast around the country. A coalition of progressive organizations in Miami called No Más Disinfo analyzed a week’s worth of content on four radio news shows after the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on January 6th, 2021.

Owner Pete Hernandez serves patrons fruit and fresh juices while listening to Radio Libre at his store in Little Havana, Miami, Florida. Photo by Jennifer A. Ortiz/Fi2W

They found numerous examples of Spanish-language broadcasts spreading false narratives, including that there was fraud in the 2020 election that no one was investigating, and incorrectly blaming Democrats and members of the Black Lives Matter movement for the insurrection. Their report highlighted how certain radio hosts were blurring the line between information and opinion by moving back and forth between news and commentary. These hosts often neglected to cite their sources, or used right-wing media sources with mixed reliability, like Epoch Times, Newsmax, or Daily Caller.

WANT MORE INVESTIGATIONS LIKE THIS?Help palabra dig deep into the stories that matter to you. Donate today! |

The audience for many of these stations are conservative Latinos. The No Más Disinfo report found that when callers on talk shows were repeating inaccurate information on the air, many times the show hosts were not correcting their statements or providing more context.

On weekdays from 6 am to 9 am, Juan Camilo Gómez writes news bulletins, shares political analysis, and takes listeners’ phone calls on the air at Actualidad Radio, a conservative news station in Miami. “The station I work at is characterized by a great deal of diversity airing on the same day,” he explained. “Some people don’t like it, because they say some of the programs are correct and others are blatantly wrong. Some people think it works really well.”

One of the shows at Actualidad was featured in the No Más Disinfo report. Gómez and his shows were not specifically named in the report, and our investigation did not find evidence that he airs mis- or disinformation. The report analyzed a different show that airs in the afternoon and is still hosted by one of the on-air personalities that the report criticized. Gómez, who has been at Actualidad for nine years, works on the morning shows. For his part, he said he focuses on his own programming, and not any of the other shows airing at the station.

‘Despite the hundreds of Spanish language radio stations and other Hispanic outlets around the country, many Latinos live in news and information deserts, places that have little or no local Hispanic media.’

Gómez does correct callers on live radio when they voice misleading or incorrect information. The day after former President Donald Trump was convicted of 34 felony counts for business fraud in New York, for example, Gómez received a call from a man claiming Trump was being persecuted politically and implying that President Joe Biden was somehow escaping impeachment. Gómez jumped in to clarify that the power to impeach Biden was actually in the hands of the Republican majority in the U.S. House of Representatives. In another instance, Gómez cut a caller off for seeming to incite political violence, saying, “at least in this program, that won’t be allowed.”

Of his role with callers, Gómez said it was an opportunity less to correct someone, and more to establish an important principle. “And it is this: you can have all the opinions you want in your heart. Nobody will try to change those. But it’s one thing to have an opinion based on a lie. And another to have an opinion based on a set of facts.”

This article is part of U.S. Democracy Day, a nationwide collaborative on Sept. 15, the International Day of Democracy, in which news organizations cover how democracy works and the threats it faces. To learn more, visit usdemocracyday.org.

|

But other Spanish-speaking radio hosts can be heard on the air doubling down on misinformation. At another radio station in South Florida, a listener called in to correct a host. “With all due respect,” the listener said, “you’ve been giving out information that I’ve been hearing, for example…” he stumbled, unused to being on the air. The listener then corrected the host for stating that there were members of the Black Lives Matter movement at the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. But the host insisted that they were there. “No,” the caller insisted, “there was not one,” he said. The host cut him off.

Gómez believes radio listeners share in the responsibility to ensure that what they read and hear is accurate. “It’s not enough to turn the radio on,” he insisted. “What’re the sources you check? And you have to know what the intentions are of these sources.”

Despite the hundreds of Spanish language radio stations and other Hispanic outlets around the country, many Latinos live in news and information deserts, places that have little or no local Latino media. There is also a huge need for information that’s multilingual and specific to geographic and cultural communities. Rather than targeting all Latinos, media needs to speak to Venezuelan business owners in South Florida, for example, or Mexican American hospitality workers in Las Vegas–much like Actualidad and Campesina do.

When these needs are not met with current, accurate, and relevant information, the void is often filled with misinformation and disinformation. Radio is a medium where many Latinos are accustomed to finding news, information, and entertainment that speaks directly to them. Ensuring the availability of reliable, quality Spanish-language programming is all the more crucial as voters prepare to cast their ballots in consequential races at the national, state, and local level.

—

This series is based on original reporting by investigative reporter Martina Guzmán. Logo design by Daniel Robles.

Stanford University journalism students Janelle Olisea, Eve Lu, and Xavier Martinez contributed to this report, as well as Irene Casado Sanchez, Big Local News data journalist.

Feet in 2 Worlds is supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Ford Foundation, the Fernandez Pave the Way Foundation, an anonymous donor, and contributors to our annual NewsMatch campaign. The Fund for Investigative Journalism provided funding for this project.

Paulina Velasco is a multilingual journalist based in California. She has made narrative documentaries and interview shows for 10 years for a variety of outlets, including Marketplace, LWC Studios, Slate, Pacifica Radio and NPR member stations. She writes for The Guardian about immigrants’ experiences in Southern California and particularly at the San Diego-Tijuana border–just 10 miles from where she grew up. Paulina was also the editor of the inaugural season of 100 Latina Birthdays, an audio documentary series about Latina health in the U.S. Her political science education helps her interrogate structures and policies, and her curiosity and empathy empowers her to accurately portray the lives of people who are often misrepresented in the media. She has lived in Mexico, France and New Zealand, and loves reading books by Latina authors — a group she one day aspires to join. Portrait by Las Fotos Project. @_pinavelasco

Jennifer A. Ortiz is a Cuban-American photographer and graphic artist born and raised in South Florida. Her work explores environments, trauma, healing, identity, histories and memory.

John Rudolph is the founder of Feet in 2 Worlds, a leader in centering immigrant voices in journalism. Created in 2004, Feet in 2 Worlds (Fi2W) is an independent media outlet, journalism training program and launchpad for emerging immigrant journalists and media makers of color. Fi2W brings positive and meaningful change to America’s newsrooms and has a broader impact on how immigration is reported and the ethnic and racial composition of news organizations. Over nearly five decades in journalism John has covered events in the U.S. and around the globe with a special focus on immigrants and immigration, U.S. politics, and environmental issues including climate change, population growth, and industrial pollution. His work has been honored by numerous journalism awards.

Martina Guzmán is the director of the Race & Justice Reporting Initiative at the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights at Wayne State University Law School in Detroit, Michigan. Her reporting covers immigrant communities and systemic inequality. She was named Best Statewide Individual Reporter by the Associated Press for her work at WDET, Detroit’s NPR affiliate. Her exploration into the rise and fall of global, post-industrial cities earned her Best Investigative Series from the Michigan Broadcasters Association and the Associated Press of Michigan. Martina was the Detroit correspondent for The Takeaway, a radio news program by Public Radio International and WNYC. She has received numerous grants and fellowships, including the MacArthur Foundation, the German Marshall Fund and a Ford Foundation, to investigate the impacts of water shut-offs on women of color in South Africa and Detroit. She is a graduate of the Journalism School at Columbia University in New York City and a 2023 John S. Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford University.