Spotting and Responding to Misinformation: A Quick Guide

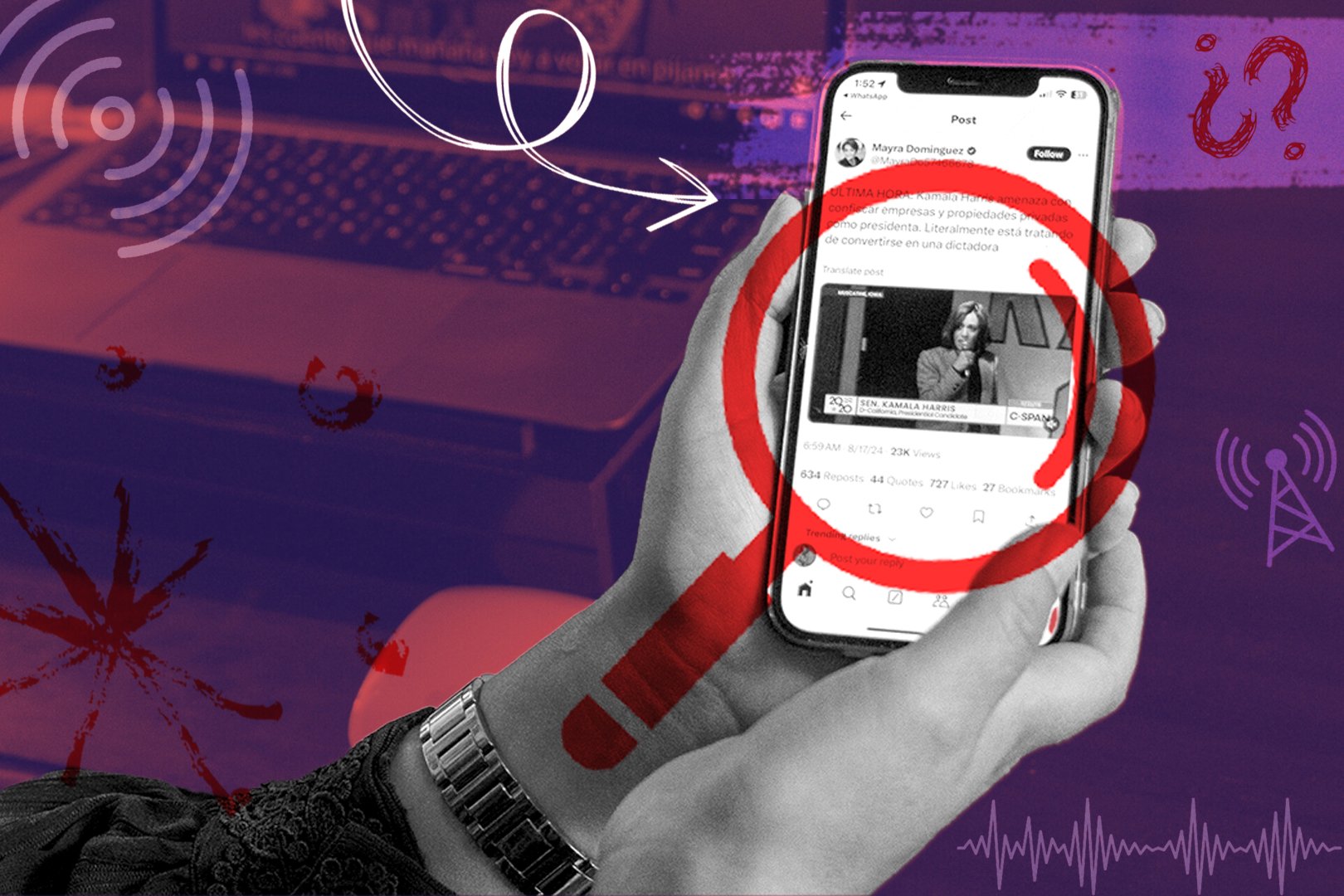

Photo by Jennifer A. Ortiz for Feet in 2 Worlds. Photo collage by Yunuen Bonaparte/palabra

Dealing with false information, rumors, and fake news by keeping an open mind and having conversations with family and friends.

Editor’s note: This explainer is part of Frequency of Deception / Radiofrecuencia de engaños, a six-part series by Feet in 2 Worlds in partnership with WNYC’s Notes from America, palabra, and Puente News Collaborative on the spread of dis- and misinformation on Spanish radio in the U.S.

This radio piece was produced by Feet in 2 Worlds in collaboration with WNYC’s Notes from America.

Haz clic aquí para leer este reportaje en español.

When Luis Antonio Perez received a text from his cousin saying they should catch up, he knew it would lead to a debate night. He says his cousin “very much embraces straight-up conspiracy theories.”

They met at a bar in Denver, where Perez lives. His cousin started sharing information he had found on social media. Perez remembers that it was around August 2023 — right after the massive wildfires in Maui. “And he was straight up saying that it's possible that the government started that fire with space lasers,” added Perez.

Perez, whose parents are from Puerto Rico and Colombia, faced a challenge experienced by many Latinos in the U.S.: deciding how to respond to a loved one when they share a piece of information that is probably false.

Fake news isn't exclusively a problem for Latinos. However, Latino immigrants often experience information somewhat differently due to their connections to their countries of origin. And because journalism in Spanish is often underfunded, misinformers often fill the void in news deserts.

In the U.S., the Hispanic population now surpasses 65 million, a 1.8% increase since the 2022 Census. As U.S. elections approach, combating misinformation and disinformation in Latino communities is crucial. According to the Pew Research Center, Latinos are the second-fastest growing group of voting-age Americans, representing almost 15% of all eligible voters. Over 36 million Latinos will be eligible to vote in November, representing a significant voting bloc.

What is misinformation and disinformation?

People may label things they understand to be false as misinformation or disinformation. Although sometimes used interchangeably, the two words have different meanings.

Disinformation is incorrect information intended to manipulate or mislead someone. For example, a troll on social media posts an image created with artificial intelligence to attack a candidate who is running for office.

Misinformation is inaccurate information shared without the intention to cause harm. For example, one of your friends is concerned about you, and they send an article that contains false information about safety in your city. Although the information is false, it was not sent to cause harm.

"Misinformation is actually the more dangerous of the two because people share in goodwill thinking that they are helping you," says Josephine Lukito, professor at the School of Journalism and Media at the University of Texas at Austin. "And it's much harder to persuade someone spreading misinformation that what they believe is false.”

Another kind of inaccurate information is malformation.

Malinformation is based on facts, but used out of context to manipulate or mislead. For example, a photo of the Hiroshima bomb — while historically accurate — could be used to represent an entirely different historical event, like the Russia-Ukraine war.

According to Lukito, in Latino communities, messaging platforms like WhatsApp play a big part in how misinformation circulates. “(Misinformation) is a very communal experience. It's coming from friends and family, and that includes family both within and outside of the United States,” Lukito explains.

How do I deal with misinformation and disinformation?

Mis- and disinformation are complicated problems that require a broad set of solutions, including laws, policies, media institutions, and education. According to experts such as Tamoa Calzadilla, editor-in-chief of Factchequeado, and professor Lukito, regulations on social media could help people identify the accuracy of the information they decide to consume.

But individuals also play a role in identifying and combating mis- and disinformation. Here are some tools and tips to navigate false and misleading information wherever we find it:

Think twice before you share

Whenever you receive any kind of information — from a friend, on the radio, online or on TV — it’s a good idea to take a moment to verify the source before sharing it with others. Whether it’s an image, meme, advice, or news, double-check the URL links to confirm where it came from. In some cases, information comes from websites that appear to be trustworthy, but are not. You can determine if a website is faking its name by checking the URL. “Look for strange symbols like exclamation marks or variations from the original links. If you notice those things, you should be more cautious of that source,” Factchequeado’s Tamoa Calzadilla explains.

“(Ask yourself) the key questions like what, when and how did this happen,” suggests Calzadilla. She says it’s important to know that “some things are too good to be true, and those that seem too terrible generally aren’t as bad. So trust your intuition and ability to understand when something is misleading.”

Share content from reputable Spanish-language outlets

Try to only share content from reputable news sources — from outlets that are already published in the language understood by those who you’re sharing with. A 2024 study from Brown University concluded that a lack of locally relevant journalism in languages other than English makes people more susceptible to disinformation and conspiracy theories. So sharing information from reputable sources in Spanish is especially important.

As a Latina born and raised in the U.S., Roselyn Almonte sometimes struggles to have conversations with her Dominican immigrant parents when they share misinformation with her. “I do speak Spanish, not 100 percent fluent,” she says. “There's a barrier where there are things that I wish I could say or say effectively, and I don’t quite have the words to do it,” she says.

“In the last couple of years, I started following Al Jazeera Plus in Spanish (AJ+ Español)," says Almonte. "I send my dad videos in Spanish created by reporters who speak Spanish. So I give him the actual facts to kind of step outside of the mostly opinion pieces my dad is sending, and that (he) pass(es) off as fact.”

Verify information with a fact-checking source

There are tools and resources you can use to verify information. Although only a few fact-checking platforms operate in Spanish in the U.S., websites including elDetector from Univision Noticias, T Verifica from Noticias Telemundo, and Factchequeado are useful resources.

Other resources like FactCheck.org and Politifact are available in English.

Be attentive of AI-generated content

WANT MORE INVESTIGATIONS LIKE THIS?Help palabra dig deep into the stories that matter to you. Donate today! |

The 2024 presidential election will be “the first presidential elections in the midst of this boom of artificial intelligence,” says Tamoa Calzadilla, from Factchequeado.

A tip for identifying fake photos is to check shadows and lighting. If some elements in the photo seem unrealistic, or the shadows in the image do not match the direction of the light, there is a chance that the images have been edited or made with AI.

Deepfakes can also appear as audio and videos. “We have seen AI being used in political campaigns to attack candidates. For example, in the New Hampshire Primary, people received phone calls with AI voice-generated messages of Joe Biden. So we have to be attentive, not scared. But attentive and prepared,” Calzadilla explains.

In those cases, you should pay special attention to the pace and the style of the speech, as AI cannot always replicate them exactly. Unnatural breath pauses and abrupt cuts can also be a sign of audio and video deepfakes.

Ask questions instead of just correcting

Using a softer and curious approach may help the other person think about the information they shared instead of feeling like they have to defend against you.

“Try asking questions like where you get that video? Are you sure it happened at the location you mentioned? When did this happen? Or kindly suggest that the information is wrong,” Calzadilla suggests.

Try to understand and empathize

Having conversations about misinformation and disinformation with people from your community can be challenging. Remember that your goal is a long-term one. You’re not just trying to prove that you’re correct in a single encounter or shame the other person. You’re trying to maintain your relationship with them and encourage good media consumption practices.

This article is part of U.S. Democracy Day, a nationwide collaborative on Sept. 15, the International Day of Democracy, in which news organizations cover how democracy works and the threats it faces. To learn more, visit usdemocracyday.org.

|

Some people have lost trust in the media. A 2024 study from The Washington Post and George Mason University found that seven in 10 residents of “six of the most important states in this presidential election… indicated that they did not have much trust or they had no trust at all” in the media.

So trying to convince someone who believes a piece of misinformation by sending them accurate information is sometimes not enough.

“It’s important to be kind,” says Calzadilla. “Avoid calling out someone in public or a messaging group where there are more people. No one wants to be exposed.”

But listening with compassion doesn’t mean you can’t question the accuracy of the information they share with you. Perez, for example, joked in a friendly way with his cousin. “I called the waiter. ‘Let's bring another shot over here. This guy needs another one!’” he said. By keeping the conversation light, Perez says, “we found a way to reconcile at the end.”

Perez says he couldn’t convince his cousin to believe that space lasers did not cause the Maui wildfires. “What I did get him to acknowledge was that there's a certain level of plausibility that needs to be acknowledged. And I got him to think critically about the gray areas.”

—

This series is based on original reporting by investigative reporter Martina Guzmán. Logo design by Daniel Robles.

Stanford University journalism students Janelle Olisea, Eve Lu, and Xavier Martinez contributed to this report, as well as Irene Casado Sanchez, Big Local News data journalist.

Feet in 2 Worlds is supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Ford Foundation, the Fernandez Pave the Way Foundation, an anonymous donor, and contributors to our annual NewsMatch campaign. The Fund for Investigative Journalism provided funding for this project.

Andrés Pacheco-Girón is an audio producer and journalist based in New York City. Originally from Bogota, Andrés is a Masters’ candidate in Podcasting and Audio Reportage at NYU’s journalism school and he interns at Feet in 2 Worlds. Before joining Feet in 2 Worlds, Andrés worked as an Associate Producer for Ballotpedia’s podcast On The Ballot and as a reporter in Colombia for Mutante, Caracol Radio, Cuestión Pública and La Silla Vacía. @apachecogiron

Mia (미아) Warren (she/her) is an award-winning audio producer living in Brooklyn, NY. With more than a decade of experience, her work has been featured on Latino USA, PRI’s The World, and in Yes! Magazine. Mia is the managing director of Feet in 2 Worlds (Fi2W), a news outlet and journalism training organization that offers fellowships and workshops to help immigrant journalists reach new audiences, improve their skills and advance their careers. Prior to Fi2W, Mia was a senior producer at Sony Podcasts, where she developed several original narrative podcast series. Mia was the co-creator and executive producer of Feeling My Flo, a podcast for teens all about menstruation. As a producer at StoryCorps from 2015-2019, she created segments for their weekly broadcast on NPR's Morning Edition, contributed to their 2019 Peabody-nominated podcast season, and collaborated on Un(re)solved, StoryCorps' Emmy Award-winning civil rights series with Frontline. @sarcasmia22

Quincy Surasmith is an audio producer and journalist based in Los Angeles, California. He is the host and executive producer of Asian Americana, a podcast featuring stories of Asian American culture and history. Quincy is also a co-founder of Potluck: an Asian American Podcast Collective, and is an alumnus of NPR’s Next Generation Radio. Previously, he was the producer-editor for the podcast #GoodMuslimBadMuslim and produced at Southern California Public Radio/LAist.

Martina Guzmán is the director of the Race & Justice Reporting Initiative at the Damon J. Keith Center for Civil Rights at Wayne State University Law School in Detroit, Michigan. Her reporting covers immigrant communities and systemic inequality. She was named Best Statewide Individual Reporter by the Associated Press for her work at WDET, Detroit’s NPR affiliate. Her exploration into the rise and fall of global, post-industrial cities earned her Best Investigative Series from the Michigan Broadcasters Association and the Associated Press of Michigan. Martina was the Detroit correspondent for The Takeaway, a radio news program by Public Radio International and WNYC. She has received numerous grants and fellowships, including the MacArthur Foundation, the German Marshall Fund, and a Ford Foundation, to investigate the impacts of water shut-offs on women of color in South Africa and Detroit. She is a graduate of the Journalism School at Columbia University in New York City and a 2023 John S. Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford University.